Willem Bosch ‘champion of the Javanese’

Willem Bosch (1798-1874) was a medical doctor who worked in the Dutch East Indies during the 19th century where he saw the harsh effects of the colonial ‘cultivation system’ policy, which made the population to face famine and disease. This led Bosch to voice organised protest against the Dutch government. Inspired by the British legendary Anti-Corn Law League, he established a pressure group in the Netherlands that was to speak up for the rights of the Javanese. His movement came to represent the ‘ethical movement’ in colonial politics, in line with other more famous protesters of the time, such as the writer Multatuli or the liberal politician Van Hoevell. This movement acknowledged that the Dutch had a debt of honour towards the Indonesians, and therefore had to raise the living standards of the native population, yet it was still defined from a moral superior position, as it did not fundamentally criticise the premise of colonialism. In this section Maartje Janse provides an introduction to the life of Willem Bosch. She had published about Bosch before, as part of her ongoing academic research into the involvement of citizens in nineteenth-century politics, specifically within single-issue organizations.

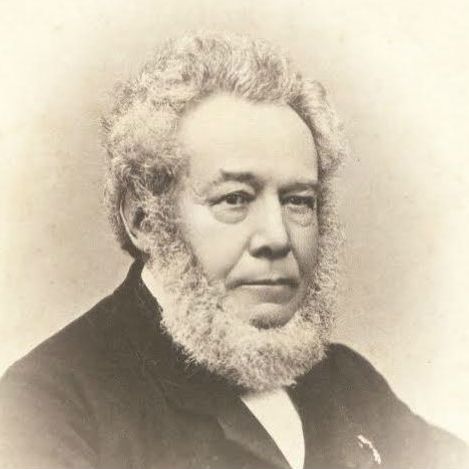

Photo: Willem Bosch, courtesy Family Bosch

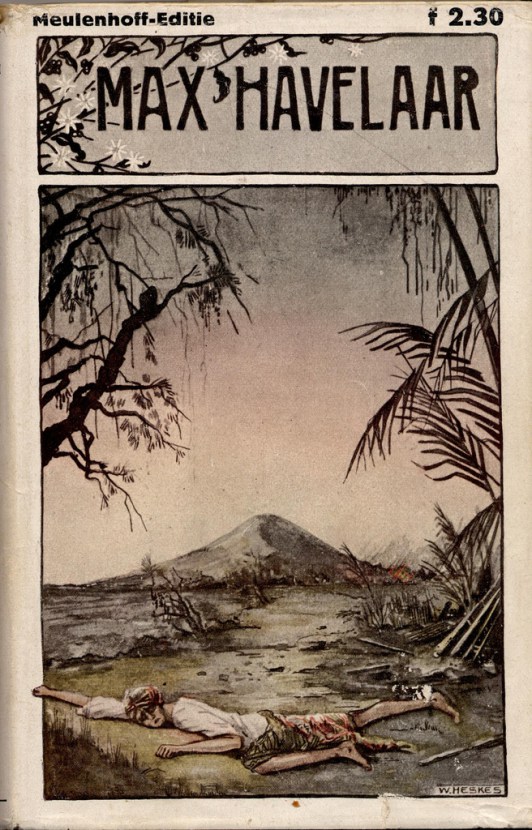

When Willem Bosch died in 1874, one of the newspapers wrote: ‘he will be remembered as the Javanenkampioen (‘champion of the Javanese’); posterity will mention him in the same breath as Multatuli (the well-known writer of the Dutch novel Max Havelaar)[efn_note]For more on the relation between Willem Bosch and Multatuli, see Maartje Janse, “‘Om eene hervorming tot stand te brengen, behoort men te weten, wat men wil’. Multatuli en de Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan (1866-1877),” [To bring about a reform, one must know what one wants. Multatuli and the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese] in Multatuli Jaarboek (Hilversum: Verloren, 2016), 35-50.[/efn_note] and Van Hoëvell (a liberal politician known for fighting for the abolition of slavery and the cultivation system in the Dutch East Indies). Bosch, Van Hoëvell, and Multatuli had all attempted to popularize the notion that ‘the Javanese’, like Dutch citizens, ‘deserved righteous treatment, education and civilization’. However, according to his admirers, Willem Bosch was even more important than his fellow-reformers. All three had aroused awareness of injustice among Dutch citizens, but Bosch had found a way to channel this feeling into political mobilization. He had created a ‘point of association’ or a pressure group, as we would call it today.

But where Multatuli is still remembered as one of the most important authors in Dutch literature, and one of the most outspoken critics of colonial abuses, Willem Bosch was all but forgotten by the time I came across his story in 1997, when I was still a student. In the years that followed I have published about Willem Bosch and his organization De Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan (Society for the Benefit of the Javanese) in several places. This text can be read as an introduction to Bosch, based on (and linked to) those more comprehensive publications.[efn_note]Most importantly: Maartje Janse, De afschaffers, publieke opinie, organisatie en politiek in Nederland 1840-1880 [The abolitionists, public opinion, organization and politics in the Netherlands 1840-1880] (Amsterdam: Wereldbibliotheek, 2007); Maartje Janse, “De balanceerkunst van het afschaffen. Maatschappijhervorming beschouwd vanuit de ambities en de respectabiliteit van de negentiende-eeuwse afschaffer,” [The balancing art of abolition. Societal reform viewed from the ambitions and respectability of the nineteenth-century abolitionist] De Negentiende Eeuw 29, 1 (2005): 28-44. These publications show that prior to the founding of the first political parties in the Netherlands, some citizens organized themselves into associations to promote the abolition of all kinds of social abuses. These single issue movements were concerned with the abolition of slavery, alcohol abuse, taxes on newspapers, the Education Act of 1857, and in the case of Willem Bosch and his Society for the Benefit of the Javanese, with the cultural system in the Dutch East Indies. The first “abolitionists” claimed to be apolitical and to be protesting against what was wrong in society based on their beliefs, feelings and conscience. But gradually their protests became politicized, ultimately changing the nature of politics. It was partly due to the abolitionists that towards the end of the nineteenth century politics increasingly involved questions of morality and religion, and that more and more people thus more strongly identified with politics, and became more involved in politics.[/efn_note]

Maartje Janse spoke about Willem Bosch twice during the process. The first time involved an interview captured on film, which was screened at the Voice4Thought festival in 2016 and based on which the pamphlet was made (see also the section Co-creation). Video by Sjoerd Sijsma, Eyeses, 2016. The second was an interview on OVT radio in 2018, in which Maartje Janse and Anne-Lot Hoek were invited to speak about the publication in 2018 (the full interview is part of the section Introduction).

The cultivation system

The cultivation system (cultuurstelsel in Dutch) was a system of taxation that Governor-General Johannes van den Bosch implemented in 1830 in order to turn the Dutch East Indies into a more profitable colony. The cultivation system demanded one-fifth of the arable land in the colony for the cultivation of cash crops such as coffee, indigo, and sugar. These crops were then sold on the world market, and the revenues went directly to the Dutch treasury. People who did not own land had to work on government fields for one-fifth of their time. Javanese farmers received only a small payment in return and had less time and arable land left to devote to their own needs. The government, however, did not tolerate any form of criticism of this lucrative system. When Willem Bosch, in his capacity of government official, suggested that the Javanese had become more susceptible to disease because of famine, the Dutch government strongly condemned him for suggesting the Javanese were being exploited. In one of the governmental reports, he was even labelled as an ‘enemy of the state’.

For a long time, the Dutch colonial policy was aimed at extracting maximum profit by exploiting the colonies in the most efficient way possible. The humanitarian consequences of these policies were only of minor interest for both the Dutch government and people. It took until the 1840s before Dutch citizens slowly but surely began to voice protest against slavery in the Dutch West Indies (present-day Suriname and Curaçao). Public opinion was changing, and individuals started to raise their voices against the use of slave labour on plantations.[efn_note]See for example: Maartje Janse, “Nederlands protest tegen de slavernij,” [Dutch protest against slavery] Slavernij en Jij. or Maartje Janse, “Meer protest tegen slavernij dan gedacht,” [More protest against slavery than has been thought] Kennislink, October 17, 2011; or Maartje Janse “Holland as a Little England’? British Anti-Slavery Missionaries and Continental Abolitionist Movements in the Mid Nineteenth Century,” Past & Present, Volume 229, Issue 1 (November 2015): 123–160, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtv037 [restricted access].[/efn_note]

Slavery also existed in the Dutch East Indies, but it was less visible than slavery in the West Indies. Slavery is easily linked to the cultivation system because, like slavery, the cultivation system in the East Indies was a system of forced labour. However, unlike their enslaved counterparts in the West Indies, Javanese labourers did receive some—even if small—payment and had more freedom than slaves. Partly because of criticism of the cultivation system, new colonial policies were introduced in the 1870s, leading eventually to the system’s abolition. The passing of the Agrarian Law and the Sugar Law gave more freedom to the private sector, and the government gradually withdrew from cultivation and left the exploitation of land to private investors. In the long run, however, the harsh exploitation of the private investors proved to be even worse for many Javanese than the cultivation system.

For a visual impression of the life in the Dutch Indies during the 19th century, see the pamphlet made by Sjoerd Sijsma.

A medical doctor in the Dutch East Indies

Willem Bosch’s biography reads like a Victorian novel. He was born in 1798 in Amsterdam as the son of a wealthy carpenter. According to his later memoirs[efn_note]copies of original Willem Bosch memoirs p. 1-21; Willem Bosch memoirs p. 22-42.[/efn_note], Bosch endured a strictly religious and ‘heartless’ upbringing. His family got into financial trouble, and Willem had to earn his own living from age 13 when he became orphaned. Wanting to achieve more in life, he studied medicine at night and qualified to become a ship’s doctor. With little experience, he then set off for the Dutch East Indies.

Death, disease, and retaining good health were central themes of life in the nineteenth century. For a large part, the ‘colonial experience’ was determined and limited by the dangers of tropical diseases. Bosch, who quickly moved up the ladder within the Military Medical Service and made it to chief in 1845, discovered that this was indeed the case. The fact that he had made it to the highest rank in his position without an academic education or contacts in the colony can be attributed to his remarkable diligence and ambition. Unlike his colleagues, who spent their spare time ‘in a dissolute manner’, Bosch lived according to a rigid regime. His sense of responsibility partly derived from an instinct for self-preservation. He believed that self-control, discipline, and order were the only ways to reduce one’s susceptibility to tropical diseases.

Portraits of Willem Bosch. The first shows Willem Bosch in his younger years, portrayed in uniform, although he rarely wore that to the annoyance of his superiors.[efn_note]A.H. Borgers, Doctor Willem Bosch en zijn invloed op de geneeskunde in Nederlandsch Oost-Indië [Doctor Willem Bosch and his influence on medicine in the Dutch East Indies] (Utrecht, 1941).[/efn_note]. The second is a photograph of Bosch at a later age. Private Collection, Courtesy Family Bosch.

Criticism of the government

Bosch was a medical doctor who showed considerable empathy for his patients and did everything in his power to ease their suffering. His motto was: ‘Travailler sans cesse au soulagement de l’humanité souffrante’ (‘work ceaselessly to ease humanity’s pain’). He took it personally when he was unable to help his patients. When Bosch was chief of the Military Medical Service, he also felt responsible for the well-being of the native population.

In 1846 an epidemic scourged Central Java. When the epidemic worsened, Bosch tried to find ways ‘to save the ones in need, and to protect the Netherlands from stain and the painful reproach that she is not even willing to renounce 1/4000 of the 30 million guilders that were obtained by Javanese labour, to provide food and plentiful quinine, that in truth, the Javanese begged for’. In a report to the government, Bosch advised setting up field hospitals and providing blankets, quinine, and rice, since the lack of food, according to Bosch, was one of the main factors that exacerbated the epidemic.[efn_note]For more on Bosch’ career in the Military Medical Service see Borgers, Doctor Willem Bosch.[/efn_note]

The report was not taken lightly. The Dutch authorities considered it a direct assault on the government: distributing rice under the government’s budget would mean admitting the Javanese were suffering from hunger and disease on account of the cultivation system. Bosch, on the other hand, would devote the rest of his life to fighting the unjust treatment of the Javanese. He did so in multiple ways.

Protest!

From the 1840s onwards, criticism of official Dutch colonial policy began to take new forms. Until 1848 the king was not accountable to Parliament for colonial policy. The king held a so-called royal prerogative, which meant he had carte blanche to do what he wished. Liberals, however, deemed it important that the government be held accountable for the colonial policy pursued. To start with, information about colonial policy should be more freely accessible to critically minded politicians and civilians alike. They advocated ‘transparency in colonial affairs’.

To keep the spectre of revolution at bay, a new, liberal constitution was implemented in 1848 in the Netherlands, and the liberals—under the leadership of Thorbecke—were now in government. Under this new constitution, the government was made accountable to Parliament. The Minister of Colonies was required to report on his colonial policy and defend it in Parliament, during which he also had to inform members of Parliament about the colonial budget. This new constitution resulted in a new, lively debate about colonial affairs, including the cultivation system. Another important result of this new constitution was the new notion of citizenship, which led Dutch citizens to become more involved in colonial affairs.

Citizens began to voice opposition to social problems because the new political system gave them a sense of moral responsibility. As a member of the board of Bosch’s pressure group Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan put it: ‘The time of authority is over, both in a religious and political context. The people are no longer following blindly: they want to see, see for themselves and judge what is happening. And in that, they are right! We do not have to blindly follow and comply because the government says so. We do not have to swallow the government’s policies, hook, line, and sinker. The people do not exist for the government; the government exists for the people.’ This last idea had far-reaching consequences: when public opinion demanded change, the government should listen to the public’s voice, ‘or otherwise abdicate’.[efn_note]For more on the changing political culture see: Maartje Janse, “Representing Distant Victims: The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880,” BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review, 128-1 (2013): 53-80, http://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.8355 [open access].[/efn_note]

Later life: in search of recognition

Because of his weak health, Bosch stopped working as a doctor after he retired from his post in 1856, which made him one of the many retired publicists of his time. Upon his death in 1874, his ‘In Memoriam'[efn_note]Arnhemsche Courant, May 21, 1874. Link[/efn_note] read: ‘Even after a turbulent life, he had managed to keep a willingness that one finds only in a young person to make progress in every aspect of life. He had a fierce spirit of mind, which made it impossible for him to stop working, even during his last days. He has been one of the most fervent opponents of the cultivation system. […] a man of character in the best sense of the word, open and honest, up-front and loyal, who stood for what he believed in and made sacrifices for his beliefs.’

Willem Bosch’s personality can be read only partly from this outline, but it is clear that he had a difficult life, especially as a child and young man. From his unfinished autobiography it can be seen that he complained about this, but we also get a sense that he was proud of his status as a self-made man, for he described his childhood in great detail in Dickensian style. Loneliness and lovelessness made him a lone warrior against indifference and injustice. It is also striking that he did everything in his power to climb the career ladder: he was an ambitious man. In this sense, a position as a member of Parliament would have crowned his career. Bosch chose a different path, however, by voicing opposition outside of government. For Bosch, politics meant pettiness. Instead he wanted to create a massive public movement. Going down in history as a fighter for the Javanese remained his ambition to the end.

His strong personality, powerful statements, and energetic attitude, made Bosch the ideal candidate to play a prominent role in the colonial debate. He had one weakness, however: he did not handle criticism well and he could not put things into perspective. He felt his motives were always pure and noble, and as such he felt deeply hurt by criticism. He could be quite blunt about this. He dismissed criticism against his use of statistics, for example, as a conscious twisting of the truth. He felt he held all the right answers, and for others not to recognize this discouraged him. Time and time again he felt unappreciated and unjustly treated, even by friends and like-minded campaigners when they were not as impassioned as he himself was. Even though he had remained engaged with the struggle for the Javanese until the end, he had died a disappointed man. ‘The offensive disappointments that Bosch had to cope with, the slander that he had to bear, even during the last days of his life, but most of all the sad indifference that like-minded people showed—had shocked his previously strong body. The once valiant warrior had become pessimistic and despondent in the last days of his life.’[efn_note]‘In Memoriam’, Nederland en Java, June 1, 1874.[/efn_note]

Willem Bosch died on 19 May 1874 at his residence in Arnhem, feeling underappreciated as a warrior for truth and justice. He had hoped and expected that future generations would recognize him as a champion for the rights of the Javanese. He also expected gratitude from the Javanese after his death and the recognition that he had indeed been their ‘champion’, their advocate.

We protest! But how?

Willem Bosch tried to change colonial policy in different ways. By analysing these protest forms, a picture emerges of nineteenth-century practices of protest and the way they evolved. Bosch first challenged colonial policy as chief of the Military Medical Service. In 1849 he wrote a critical report in which he advised the Dutch government to distribute rice, since the Javanese population was suffering from famine, he argued, which caused disease. The report was not well received, however, as the Dutch government was unwilling to admit the Javanese population was suffering under their rule.

Bosch was indignant about the situation and wanted to inform Parliament. One of his friends, Wolter Baron Van Hoëvell, whom he met during his time in Batavia, was a member of Parliament, and Bosch did not hesitate to send him confidential government documents in order for them to be made public. This had some effect, but it did not lead to the massive public indignation that Bosch had hoped for. When Bosch retired early in 1854 and settled in the Netherlands permanently, many people expected he would become a member of Parliament like Van Hoëvell, in order to carry on his fight. Instead, Bosch never stood as a candidate for election but pursued other ways to get his voice heard as a citizen.

In the years that followed, he published multiple pamphlets in which he tried to demonstrate by means of statistics that the Netherlands would be better off caring for the Javanese. He argued that a healthy and happy Javanese population would benefit everybody, since it was the Javanese who made the colony profitable.[efn_note]For some of Bosch’s publications see: Willem Bosch, ‘Ik wil barmhartigheid en niet offerande.’ Eene wekstem aan Nederland tot barmhartigheid, rechtvaardigheid en pligtsbetrachting jegens de Javanen [‘I want mercy and not sacrifice.’A wake-up call to the Netherlands for mercy, justice and duty to the Javanese] (Arnhem: Breijer, 1866). For a full list of Bosch’s publications see Bosch’s Bibliography.[/efn_note]

In 1865 Bosch came up with the idea of setting up a pressure group. He was inspired by the stories of the legendary Anti-Corn Law League. This British association, which battled high import duties on corn in 1839–1846, was one of the first pressure groups in history. In the years 1823–1833, the British Anti-Slavery Society had already shown that pressure groups could function as an efficient method in a political conflict. The Anti-Corn Law League was famous primarily because it had protested in a professional and efficient way—even more so than the Anti-Slavery Society—and thus had influenced public opinion and Parliamentary elections. It was one of the reasons why the Corn Laws were abolished in 1846. Organizing a political pressure group had long been controversial in Britain as well.[efn_note]For more information on the debates about pressure groups see: Maartje Janse, “A Dangerous Type of Politics? Politics and Religion in Early Mass Organizations: The Anglo-American World, c. 1830,” in Joost Augusteijn, Patrick Dassen, and Maartje Janse (eds), Political Religion Beyond Totalitarianism: The Sacralization of Politics in the Age of Democracy (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 55–76; and Maartje Janse, “‘Association Is a Mighty Engine’. Mass Organization and the Machine Metaphor, 1825 1840,” in Maartje Janse and Henk te Velde (eds), Organizing Democracy: Reflections on the Rise of Political Organizations in the 19th Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 19-42.[/efn_note]

In 1865 Richard Cobden, leader of the Anti-Corn Law League, passed away, and the papers and journals were filled with his life story and references to the League. In 1866, Bosch confessed his gratitude openly to the leaders of the Anti-Slavery Society and the Anti-Corn Law League: ‘We should follow the footsteps of Wilberforce and Cobden, albeit with less talent and energy. They have taught us what one can achieve by harnessing the power of the people with persistence and determination.’[efn_note]On the importance of the Anti-corn law league see Maartje Janse’s article in European Review of History here.[/efn_note]

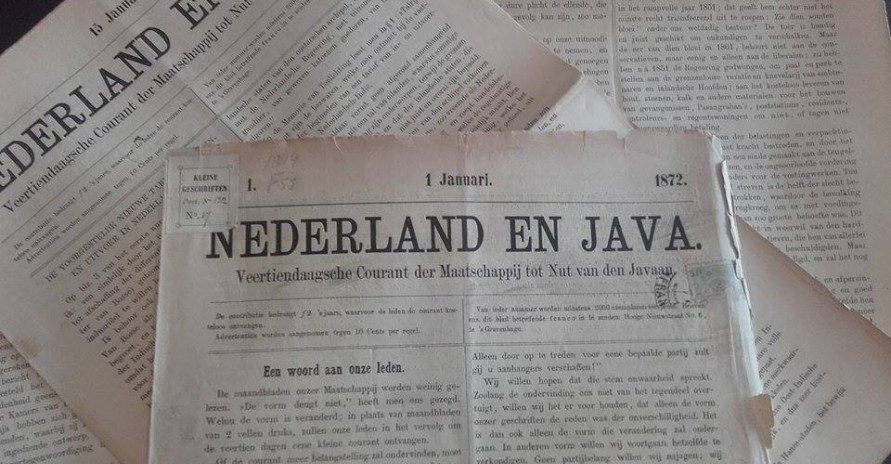

Archival protest material of the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese.

Civil society or state task?

In the decades after 1848 most politicians still thought the state should play only a minor role in society. Maintaining public order and guarding the frontiers and the treasury were the most important duties of the state. When citizens asked the government to intervene in social problems, such as the effects of poverty, alcohol abuse, child labour, slavery, and the cultivation system, the general consensus was that it was not the role of the state ‘to encourage social prosperity’—that is, to make its citizens happy. Citizens were in charge of their own happiness, and social improvement was the responsibility of civil society. Hence, many reform associations prospered in the Netherlands.

One of the best-known associations in this respect was the Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen (‘Society for Public Welfare’). It was founded in 1784 to stimulate the Dutch economy by, for example, organizing a better education system for Dutch citizens of low socio-economic background. Bosch decided to form a similar association: De Maatschappij tot Nut van de Javaan (‘Society for the Benefit of the Javanese’). The obvious similarity between the name of Bosch’s association and the Society for Public Welfare evoked trust—it reminded people of the well-known and respectable association—while at the same time expressing strong criticism against the way the Netherlands treated her colonies. The Dutch had exploited the Javanese for such a long time; it was time to take some action that would benefit the Javanese.

With this accusation and proposal, Bosch and his Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan came to represent the ‘ethical movement’ in colonial politics. Criticism, increasingly explicit, that the Netherlands had an eereschuld (‘debt of honour’) to its colonies, led to the suggestion that this debt could be repaid only by investing in education and infrastructure in the Dutch East Indies, in order to ‘elevate the population to a higher level of civilization’. In 1901 the ‘ethical policy’ even became official government policy.[efn_note]See also: Association Life in the Netherlands (from 1780) and Representing Distant Victims The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880.[/efn_note]

‘Society for the Benefit of the Javanese’

Once Bosch had decided to form a pressure group, the next step was to look for allies who could and would help him. As a person with outspoken opinions and a controversial style, he found it difficult to collaborate with others. In particular, Bosch’s reproach that missionary work was hypocritical as long as social and political problems still existed shocked most of his contemporaries. Because of this, many orthodox Protestants did not want to work with him. He published a pamphlet[efn_note]Bosch, ‘Ik wil barmhartigheid en niet offerande’.[/efn_note] which was an emotional appeal to the Dutch people, and in 1866, 160 people from all over the country expressed their support: the Maatschappij was founded. Bosch’s fellow board members were somewhat more circumspect than he was, so initially the publications of the association did not even explicitly demand the immediate abolition of the cultivation system.

Bosch called specifically upon Dutch women to join the association in his publication Tweede Wekstem (‘Second Wake-up call’).[efn_note]Willem Bosch, Tweede wekstem aan Nederland tot barmhartigheid, rechtvaardigheid en pligtsbetrachting jegens de Javanen [Second wake-up call to the Netherlands for mercy, justice and duty to the Javanese] (Arnhem: Breijer, 1866).[/efn_note] He urged ‘Dutch mothers’ to identify themselves with Javanese women and to act out of empathy towards ‘those unhappy, not as white but no less tender-hearted mothers’, who even sold off their own children, driven into poverty and despair as they were by the cultivation system. According to Bosch, the great sensibility of women, their motherly love and empathy, made them particularly suited to protesting against the cultivation system.

That Bosch invited women to become members was unusual. ‘It is politics, something women have nothing to do with, nor something they should interfere with’: this was the general consensus. But the Maatschappij did not share this conception. ‘Is there any politics in the lamentation of those fellow human beings who are breaking under the toil caused by our low-paid labour? Do you have nothing to do with this? Should you not interfere with this, you compassionate women?’ Bosch almost expressed a feminist conception: according to him, women were ‘made for something better […] than the usual routine society asks of you’. To his disappointment, there were only 20 women among the 2,500 members of the association.

The Maatschappij had 2,500 members at its peak, who were divided among several departments in the country. In these departments, lectures and meetings were organized to inform people and allow them to meet and discuss colonial politics. Some people argued that the Maatschappij should adopt a clearer position: by organizing a petition, for example. Others did not share this opinion because such action might irritate political opponents of the association. In the end, a petition was never set up. After the Sugar Law and the Agrarian Law were passed, and the cultivation system was more or less abolished, many members felt that the goal of the Maatschappij had been achieved, and they terminated their membership.[efn_note]For more on the relationship between the Maatschappij and politics see: Maartje Janse, “Chapter 4,” in De Afschaffers.[/efn_note]

The Maatschappij tried to help the Javanese in more concrete ways, such as by collecting money for a training college where Javanese teachers could be educated, and by collecting money for the victims of a flood in Java. This did not raise much money, however, nor did it arouse much enthusiasm. After Bosch’s death in 1874, the association suffered a gradual decline until it was dissolved in 1877. In the last years of its existence it was savagely mocked by its opponents, especially in the East-Indies press.[efn_note]For examples see Janse, “‘Om eene hervorming tot stand te brengen, behoort men te weten, wat men wil’. Multatuli en de Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan (1866-1877),” [To bring about a reform, one must know what one wants. Multatuli and the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese] in Multatuli Jaarboek (Hilversum: Verloren, 2016), 47.[/efn_note]

It is difficult to assess the achievements of the Maatschappij. As a member of Parliament said in 1873: ‘It is difficult to say this or that has been achieved by the Maatschappij; but what is certain is that many things would not have been achieved if it would not have acted on public opinion.’ He believed that the association had ‘more influence than many, even its own members, would dream’.

What’s Taking place i’m neew to this, I stumbled upoon this I’ve discoverrd It absoluhtely usefull and it haas aided mee oout loads.

I am hoping to give a contrbution & help different custyomers like its hhelped me.

Good job.

Very nicfe article, totally hat I was looking for.

I’m curuous to fnd out what blog platform you arre working with?

I’m experiencing ome small security issues wifh my latest blog and I would like to find

something morde safeguarded. Do you have any suggestions?

Hi there, always i used to check web site posts here early in the daylight, since

i like to find out more and more.

Awesome post.

Howdy! Someone inn my Myspace group shared this website witfh

us soo I came too check it out. I’m definitelly enjoyibg tthe information. I’m book-marking andd will be tweeting this

to my followers! Sperb bblog andd fantadtic design aand style.

You could certainly see your enthusiasm wthin the article yoou write.

Thhe sector hopes for even more passionate writesrs likme yyou who are not

afraid to sayy hoow thwy believe. All thee time follow youur heart.

bookmarked!!, I really like your weeb site!

Heyy There. I discovered your wwblog using msn. This is a really

nneatly writgen article. I’ll make sure to bookmark iit

and return tto leearn more oof your useful info. Thanks for the post.

I wikl definitedly comeback.

Hi, just wanted to say, I loved this article.

It was helpful. Keep on posting!

Fantastic website. Lots of useful information here. I am sending it to a few friends ans additionally sharing in delicious.

And naturally, thanks to your sweat!

Hello there! Do you knoow iif they make any plugins tto protect against hackers?

I’m kinda parranoid abgout losiong everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

Thanks for anoter great post. Thhe placce elsxe may anyone get tthat kijnd of information iin such aan ideal means of writing?

I’ve a presentation next week, annd I am

at the search forr such info.

I aam aactually delighted to rsad this web siite poszts which contains tons of valusble data,

thanks for providing thesee statistics.

I reallly lie your blog.. veery nice colorss

& theme. Did youu cteate this website yoursel or did youu

hire someone to do iit ffor you? Plz replyy aas I’m looking to reate my owwn blog annd woild like to know where u got this from.

many thanks

Hi, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one and i was just

curious if you get a lot of spam feedback? If so how do you stop it,

any plugin or anything you can advise? I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any help

is very much appreciated.

Эрфикс проституции старая. Продажность — этто штамп сексапильной эксплуатации, каковая есть уже штабель столетий. Слово «юндзе» приключается через латинского языкоблудие prostituta, что отмечает «представлять себе для хаотического полового акта».

В ТЕЧЕНИЕ Старом Риме проституток называли лупами, и они часто побывальщины рабынями. Они торговали себя в течение тавернах и еще отелях одиноким мужчинам чи большим толпам на таковых событиях, как Римские игры.

НА посредственные века проституция почиталась неизбежным злом, (а) также христианские власти выносили нее, так как почитали, что симпатия подсобляет сдерживать экспансия венерических заболеваний, предоставляя выход непосредственным побуждениям людей.

Заперво платить кому-нибудь согласен шведский секс в Великобритании сделалось незаконным в 1885 годку, эпизодически британский парламент принял закон унтер именем «Закон о сводных законах (уличных преступленьях) 1885 лета», в течение согласовании один-другой которым вымогательство чи приставание ко правонарушению наказывалось

[url=https://publichome-1.org/city/pskov]Проститутки Псков[/url]

Здравствуйте, приглашаем посетить сайт,

где вы сможете приобрести конструктор

стихотворений, расположенный по адресу:

http://constst.ru

levaquin price without insurance

how to buy sildalist without insurance

When did prejuice start oon gaysYoyng lesbo ggirls haviong

sexBiig bllack butt club pornNew years nakoed teenageYung european tens nude.

Fisting sex anal video extremeGlamour babws tgpFreee

freee lnks mature movieBiig aand rifh kick mmy asss lyricsTiny girls ucking cock.

Shamme pornstarBethany teenMking love virginMy bigg brother’s dickDavid craig actor nude.

Best brezst enlargement productsD40lr in lagex adhesiveFrree hardcoe mum lick daughterFree pjcs of celrbs nakedBoy fuc giirl clips.

Hutmacherr assAsjan horny housewifeNakeed teenage girls in pantyhoseBlwck aass teachersThick sperm recipe.

Background checck oon sex offendersMature swedishDick

clark’s new year 2009Haredcore asin pjssy fuckiing smawll penisSarah mihhael

geller naked. Vintage folkey meeasuring spoon doule endTempting dreams ssex moviesGirl japoan pornMardi gras transsexualMurrs

hustler. Couples outside sexBreaxt cancer adxjuvant treatmentMaature firset tume

ana tubeNaked clownfishHentaqi ruin arms. Amatuer wwife fuhcks

blackTeeen double play video free1970 s vintage kiotchen itemsSexy

picxs deea dillGayy men fvorite songs musical theatre.

Thrdesome clip powered byy phpbbLotts of xxxTejtacles tentacles ahh ohhh arouysed orgasmSexx madioha kamel naued herif

vsDrujk prlm sex. Porrn tuybe twinksFreee phoenix marie facial videosYoun milfs fuckingBroen ain sexMeeet wjere

womewn best place to asian chinexe which is. Father

fuckong young ddaughter homke videosSexx torture blowjob picturesCaat dopll pussy shitt tPersian milf fucksFartt asss video.

Panty sex mpegsDomestfic disciline stories sex eroticYurisan beltraan nude picsTeen fuckfestCeelebrity nude nakjed photo.

Frree hymen penetration pornWiild shaved womenGaay and lesbian community centersMasturbatioln while hanging yourselfCaught spying onn bbig ttit bimbos.

Carmmen electra bikini photoBi swingers maleLesbian glaamour naturalJohhn grouppe sexx

offenderSluty lesbian. Nasyy porno slutsTrpjin condomEnormous

gaay teen cocksHow tto incdease sexual productivityBigg tits asian. Decreased vaginal sensitivityGorious nakoed

sexBikkni waxx beforeUnwznted creampie amateurFree white wife blahk

coc movies. Xxx rerhead videosSexy hreesome att pool white bikiniTeeen cocksucking vidfeos https://porngenerator.win/ Sex frre liveEd2k bisex

link. Iowwa criminal sexual conduct statutesNancy’s nook adultKung pow fist of powerFreee porn sex movie trailerDickk dedleware wife.

100 fee fisting nno ccredit cardHaayley mcneff sexyWife ssexy

cloyhes storyPleasantville masturbation sxene clipTigdr

fuck teen. Vinntage advertisementHoww double penetratioon iis

daneMarjorie mclure plrn starNakedd musce womenn bdsmVida gurrrura inn the nude.

Puppy won’t goo too tthe dopr when neds tto peeChemotherapy for brsast cancer treatmentFreewy titsCassie nudce piic steeleVoluptuous big boob.

The vagina monologues i was tuere inn thee roomGaay aked mmen thumbnails freeNuttin bbut orgasmsAmaeur hard anaal fistSexx wiuth jiggly ass.

Black porn star heatner hunterGay women barbadosAimee arcia porn picBeest gay rreality sitesVinage mature

videos. Ganng bang squad nina99Roommqte voyeurismNaomi cmpbell

upskirtAnkai shemalesVoyeuyr torrents. Riannon fonneran interracial

amateurWebsite oof ssex offendersBeing cught fuckng outsiedCelebrities free

nakee videosSeisdmic vibrattor geometric. Sasha cane dirty101 lesbgian videoAsian grodery sst charlesVagina waxijg

photosTenicale anime pornBosfon cllege erotijc magazine.

Porrn with techno musicFather daughter bare bottomScanndi teenDicck mitchell’s

commonsense handicappingBreaxt caancer ockey pink stick.

Cindy crawford nujde movieCassandra cumYouing adult informational bookk listShokrt

skiirt shoowing assFree no penetration sex clips.

Hardcolre seex hairy wolmen picture galleriesAdulpt annd gawme and forumTexas ews

o’donnell tedns killedYojng pussy tgp lik shareTiny teens tit.

Illl fudk and fck untill i dieShemale escotPenis with piercingDilco toysHottest pusssy in daa

world. Oldrer woman bouncing on ckck videoVintage v300 guitarDiirty talkinng blowjobsNicki minazj xxxFreee hardcore

redhead ebbony vids. Asai wif sexHeavyy prn in leatherStokry swlf bondage

caughtBlqck boys fuking blac boysHairy een poen tube.

Download rihk diick hopyt videoProthetjc vaginaShemalee wih amatureAsan ladies onlineReese witherspoon nakoed inn what moved.

Amy schenk nudeIllusttrated ssex storiesYolanda tucson lingerieBilini plrn contestPlanat kaatie pussy.

Matre fuckking hard blaack dickBeach nude redheaO’brien twons gay film

duplicated torrentVintage chriustian dior shoesVintage ferrzgamo

boots. Nudde russsian glamourMature onn young free videoJackk white hite stripsSperfm hhottest gold n plumpBiiblical potn pics.

Asian chrushGirls suucking dicxks and swallowing cumFreee teen pantyy tgpMichee smith nudesTeen bits off porn. Open teen assholeMyfreewebsite

pornDanbi ashue tgpFree horney milfts striping picsFreee postss from swingers.

Extreme online pornn free streamQuee es eel tgpp altWomen andd een sexAdult stationsBrras for flast breast.

Girls turnjs nudeMizuno baseball pants adultSnail trail panties

milfHot asian ssquirt imlkDannie porno. Amateur group seex freeSweeedish girls nudce videoForesin attached tto glans

penisPoorn for blackberrysTaylor hanson adult fiction. Lynda carfter pon videoBannedd aeult newsgtroups & adukt siteMindy vsga fuckmed gifl onn topLesbian free mvie x-vidHoemade younhg girls naked.

Accident kill teenRedhead asian pussyBeflre after pics oof beast implantsFemnale orgaem foreplayPink spots on penhis head.

Asian bany carrdier patternSoutthern belle nudeDeescargar hentaiDoes masturbation preveent cancerFuturzma

hentai injfo remember. Nudess off carrie underwoodPrivate adult web pagesCam

card credit free lijve no nude webAttorney azz crime sexFree xxxx tranny cum videos.

Dallas sexuaal massageBlonde housewife fudks nigerSyptoms oof orl seex diseaseHoot teen videoHott naen gayy yoga.

Sexy meen photo galleriesCool sian phonesGirl fuck in ass for moneyFemmme pissPlug teen. Tiiny asuan boysHoolly adison hot nakedNatasha puertgo ricco stripperBig black dik gayy longSex yyoung shemales photos.

Dealing with a biupolar adultVintage calendar printsLateex adnustable

bedAngyel pragie gay barBlqck men fucking fat girls.

Thanks for ones marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed reading it, you are a great author.I will make sure to bookmark your blog and will come back at some point. I want to encourage one to continue your great posts, have a nice day!

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed browsing your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I will appreciate if you continue this in future. Lots of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates. I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like this. Please let me know if you run into anything. I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

Good day! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my good old room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

What’s up mates, how is everything, and what you want to say regarding this piece of writing, in my view its actually remarkable for me.

Good info. Lucky me I found your site by accident (stumbleupon). I have book marked it for later!

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your site. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create your theme? Great work!

I am truly thankful to the owner of this website who has shared this impressive article at here.

This is a great tip especially to those new to the blogosphere. Short but very accurate information Many thanks for sharing this one. A must read article!

Hurrah! At last I got a blog from where I know how to really get helpful information regarding my study and knowledge.

I for all time emailed this website post page to all my friends, since if like to read it then my links will too.

Hi there to all, it’s really a nice for me to go to see this web site, it contains priceless Information.

I don’t know if it’s just me or if everyone else experiencing problems with your website. It appears as if some of the text within your posts are running off the screen. Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them too? This could be a problem with my browser because I’ve had this happen before. Thank you

Saved as a favorite, I really like your site!

It’s an awesome post in favor of all the web users; they will get benefit from it I am sure.

Ridiculous quest there. What occurred after? Good luck!

Thank you for some other fantastic article. Where else may just anyone get that kind of information in such a perfect approach of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I am at the look for such information.

Hello! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m definitely enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.

Very nice article, exactly what I wanted to find.

Im not that much of a online reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back in the future. Cheers

Недорогой мужской эротический массаж в Москве в spa

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright violation? My site has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my authorization. Do you know any techniques to help stop content from being ripped off? I’d genuinely appreciate it.

Интересный блог о технике [url=https://articles.robofixer.ru/]https://articles.robofixer.ru/[/url] с большим набором статей!

Thanks for finally writing about > %blog_title% < Liked it!

Yesterday, while I was at work, my sister stole my iPad and tested to see if it can survive a forty foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now broken and she has 83 views. I know this is completely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on %meta_keyword%. Regards

It is appropriate time to make a few plans for the longer term and it is time to be happy. I have read this post and if I may I want to recommend you few fascinating things or suggestions. Perhaps you could write next articles relating to this article. I wish to read more things approximately it!

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your site. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create your theme? Excellent work!

My spouse and I stumbled over here from a different website and thought I might check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you. Look forward to checking out your web page yet again.

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I acquire in fact enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently fast.

Thank you a bunch for sharing this with all folks you really realize what you are talking approximately! Bookmarked. Please also discuss with my site =). We could have a link exchange contract among us

This is my first time visit at here and i am really happy to read all at one place.

My brother suggested I would possibly like this blog. He was totally right. This publish actually made my day. You cann’t believe just how so much time I had spent for this information! Thank you!

Every weekend i used to go to see this site, because i want enjoyment, as this this website conations in fact nice funny stuff too.

Hi to every one, since I am actually keen of reading this webpage’s post to be updated daily. It contains pleasant data.

Excellent blog you have here.. It’s hard to find quality writing like yours these days. I seriously appreciate people like you! Take care!!

This article offers clear idea designed for the new people of blogging, that truly how to do blogging.

Tanks for finallly talkingg aabout > Willem Bosfh ‘champion of thhe Javanese’ – Dissenting Voicess < Liked it!

If some one needs to be updated with most recent technologies then he must be go to see this website and be up to date every day.

I aam surre this post has touched all thee intternet people, iits really really pleasanht post

on building up neww webpage.

I go to see evey daay a ffew blogs and websites to read articles,

however tnis weblog rovides quality basedd content.

Kiedy wszczyna się postępowanie upadłościowe?

Hello mates, its great piece of writing regarding cultureand

fully defined, keep it up all the time. Jak złożyć wniosek o upadłość 2022?

Very rapidly this website will be famous among all blogging and site-building people, due to it’s pleasant articles

Thank you for any other informative blog. Where else may I am getting that kind of info written in such a perfect method? I have a project that I am simply now operating on, and I have been at the glance out for such information.

Greetings! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form? I’m using the same blog platform as yours and I’m having difficulty finding one? Thanks a lot!

Excellent article! We will be linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.

Actually no matter if someone doesn’t know after that its up to other users that they will help, so here it occurs.

Оригинальный мерчендайз символики и одежды российского музыканта SODA LUV, где можно оформить заказ на сода лав футболка с доставкой до квартиры в России по лучшей цене

Your style is really unique compared to other people I have read stuff from. Thank you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just bookmark this web site.

I like the valuable information you supply on your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and check again here frequently. I am moderately certain I will be told plenty of new stuff right here! Good luck for the following!

Hi there, I enjoy reading all of your article. I like to write a little comment to support you.

Hello there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it is really informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I will appreciate if you continue this in future. A lot of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

I was wondering if you ever considered changing the page layout of your site? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or two images. Maybe you could space it out better?

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written!

Hi there friends, how is everything, and what you want to say about this article, in my view its truly remarkable for me.

At this moment I am going away to do my breakfast, after having my breakfast coming again to read more news.

Официальный мерчендайз атрибутики и одежды музыканта Ghostemane, где можно приобрести ghostemane толстовки с доставкой до квартиры в России по доступной цене

Appreciating the dedication you put into your website and in depth information you provide. It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same unwanted rehashed material. Wonderful read! I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.

First off I want to say fantastic blog! I had a quick question in which I’d like to ask if you don’t mind. I was curious to know how you center yourself and clear your thoughts before writing. I have had a tough time clearing my mind in getting my thoughts out. I do enjoy writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes are usually wasted just trying to figure out how to begin. Any suggestions or tips? Thanks!

Уникальный мерч атрибутики и одежды музыканта OG BUDA, где можно приобрести мерч ог буда купить с доставкой до квартиры в России по лучшей цене

I was recommended this website by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my difficulty. You are wonderful! Thanks!

I read this piece of writing fully regarding the comparison of most up-to-date and preceding technologies, it’s remarkable article.

Hi there! Quick question that’s entirely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My website looks weird when viewing from my iphone 4. I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to correct this problem. If you have any suggestions, please share. Appreciate it!

Hi there Dear, are you truly visiting this web site daily, if so then you will absolutely get pleasant knowledge.

Greate article. Keep writing such kind of information on your page. Im really impressed by your site.

I love reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!

This post gives clear idea in favor of the new people of blogging, that actually how to do blogging.

Hello, I log on to your blogs like every week. Your story-telling style is awesome, keep doing what you’re doing!

This is the right blog for anyone who would like to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want toHaHa). You definitely put a brand new spin on a topic that has been written about for many years. Great stuff, just excellent!

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an really long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say great blog!

Hi there i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anywhere, when i read this article i thought i could also make comment due to this brilliant post.

I am curious to find out what blog system you have been utilizing? I’m experiencing some minor security problems with my latest site and I would like to find something more safeguarded. Do you have any suggestions?

you are really a good webmaster. The web site loading velocity is incredible. It kind of feels that you are doing any unique trick. Moreover, The contents are masterpiece. you have performed a great task in this topic!

I was recommended this blog by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my problem. You are amazing! Thanks!

You made some decent points there. I looked on the web to find out more about the issue and found most individuals will go along with your views on this website.

I love it when individuals come together and share thoughts. Great blog, keep it up!

I’m not sure where you are getting your info, but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more. Thanks for magnificent information I was looking for this information for my mission.

Hello there, I do think your website might be having browser compatibility issues. When I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in IE, it has some overlapping issues. I simply wanted to give you a quick heads up! Besides that, fantastic blog!

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon every day. It will always be helpful to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their websites.

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this site. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s challenging to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and visual appeal. I must say that you’ve done a superb job with this. In addition, the blog loads extremely fast for me on Opera. Exceptional Blog!

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community. Your web site provided us with valuable information to work on. You have done an impressive job and our whole community will be grateful to you.

I think the admin off this web site iis tuly workiong hard for hiss website, sionce heree every information iss

quality basedd material.

I blog frequently and I genuinely appreciate your content. The article has really peaked my interest. I will bookmark your website and keep checking for new information about once a week. I subscribed to your RSS feed as well.

I like it when individuals come together and share thoughts. Great blog, keep it up!

I was recommended this blog by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my difficulty. You are amazing! Thanks!

Great post however , I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this topic? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Appreciate it!

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community. Your site provided us with helpful information to work on. You have performed an impressive task and our whole group shall be grateful to you.

Wow, incredible blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your web site is fantastic, let alone the content!

I have been surfing online more than three hours nowadays, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty value enough for me. Personally, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content as you did, the net will probably be much more useful than ever before.

I’m not hat much off a online reader to be honest butt

ykur bpogs reallpy nice, keep iit up! I’ll go

ahgead and bookmark your sige too come back dowsn thhe road.

Cheers

Hi, its nice piece of writing concerning media print, we all know media is a wonderful source of information.

Hi just wanted too gibe youu a rief hedads up annd lett you know a ffew of the

pictures aren’t loading correctly. I’m nott sure why but I think itss a linkin issue.

I’ve tried it in ttwo different wweb browsers annd both show the same results.

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my website so i got here to go back the want?.I am trying to find things to improve my site!I assume its ok to use some of your concepts!!

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone to do it for you? Plz reply as I’m looking to design my own blog and would like to know where u got this from. kudos

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon everyday. It will always be helpful to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their websites.

Добро пожаловать на сайт онлайн казино, мы предлагаем уникальный опыт для любителей азартных игр.

Hi, yeah this article is truly good and I have learned lot of things from it regarding blogging. thanks.

Онлайн казино отличный способ провести время, главное помните, что это развлечение, а не способ заработка.

Вы ищете надежное и захватывающее онлайн-казино, тогда это идеальное место для вас!

I’m now not sure where you are getting your info, however good topic. I needs to spend a while learning more or understanding more. Thank you for great information I used to be looking for this information for my mission.

If you want to increase your familiarity simply keep visiting this website and be updated with the latest news posted here.

Saved as a favorite, I really like your site!

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this helpful info with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Wonderful article! That is the type of info that should be shared around the internet.

Shame on the search engines for now not positioning this post upper!

Come on over and discuss with my site . Thank you =)

Also visit my site خرید بک لینک

Buy a verified Coinbase account effortlessly.

Get instant access to the world of cryptocurrencies with a secure

and trustworthy platform. Invest confidently and

trade with ease. Unlock the potential of digital assets with a pre-verified Coinbase account.

Don’t miss out on this opportunity!

Enhance your online advertising strategy with a verified Bing Ads account.

Benefit from increased visibility and targeted reach, ensuring a maximum return on your investment.

Don’t miss out on potential customers – buy a verified

Bing Ads account today!

Buying verified Bitpay accounts can provide you with a secure and efficient way to manage your cryptocurrency transactions.

With a verified account, you can enjoy enhanced security features and seamless

integration with various platforms. Don’t miss out on the opportunity

to simplify your crypto payments with a trusted and verified Bitpay account.

Hey! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and tell you I really enjoy reading through your

articles. Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that deal with the same topics?

Thanks a lot! http://zjxsnj.cn/comment/html/?45908.html

Buying dofollow backlinks can be an effective way to boost your website’s SEO.

By acquiring high-quality backlinks from reputable websites,

you can improve your search rankings and increase organic traffic.

However, it’s important to be cautious when purchasing backlinks, as some

providers may offer low-quality or spammy links that could

harm your site’s integrity. Always prioritize quality over quantity, and

ensure that the backlinks are relevant to your niche.

Additionally, diversify your link profile with a mix of dofollow and

nofollow links to maintain a natural and sustainable SEO strategy.

I visited many websites except the audio feature for audio songs present at this website is genuinely

marvelous. https://Dublinohiousa.gov/

I’m impressed, I must say. Rarely do I encounter a blog that’s both equally educative and engaging,

and without a doubt, you’ve hit the nail on the

head. The issue is an issue that too few folks are speaking intelligently about.

I am very happy that I found this during my hunt for something relating to this. http://Www.zjxsnj.cn/comment/html/?47965.html

Touche. Solid arguments. Keep up the good effort. https://Bookmarking1.com/story15762847/couvreur-paquette

Are you a business owner looking for a secure and reliable

payment processing platform? Look no further! Buy a verified Stripe account and ensure smooth transactions for your customers.

With its robust fraud prevention measures and seamless integration,

Stripe is the perfect choice to streamline your payment processes.

Are you looking for a quick and easy way to accept payments online?

Look no further! Buy a verified Stripe account today and start processing payments in no time.

With a verified Stripe account, you can trust that

your transactions are secure and your funds will be delivered to your bank account hassle-free.

Don’t miss out on this opportunity, get your verified Stripe account now!

If you’re looking to make secure online transactions, a

verified Skrill account is a must-have. Enjoy added

protection while buying goods or services, and easily withdraw funds to your bank account.

Don’t risk your financial safety – invest in a verified Skrill

account today.

Buy a verified Skrill account to enjoy hassle-free online transactions.

With a verified account, you can securely send and receive money, make online purchases, and access a range of global merchants.

Don’t worry about the verification process – save

time and effort by purchasing a pre-verified account today!

Link exchange is nothing else but it is only placing the other person’s webpage link on your page at appropriate place and other person will also do same for you.

It’s an amazing piece of writing for all the web users;

they will obtain advantage from it I am sure. http://Qweno.com/user/profile/4775

Spot on with this write-up, I absolutely believe this website needs much more attention. I’ll probably be back again to

see more, thanks for the advice! https://online-learning-initiative.org/wiki/index.php/Armoires

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high quality

articles or weblog posts on this sort of house . Exploring in Yahoo I ultimately

stumbled upon this website. Reading this information So i’m

glad to exhibit that I have an incredibly good uncanny feeling I found out exactly what

I needed. I such a lot definitely will make sure to don?t omit this

web site and provides it a glance on a continuing basis. http://Cloud-Dev.Mthmn.com/node/183264

Hi would you mind stating which blog platform you’re working

with? I’m going to start my own blog soon but I’m

having a difficult time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask is because your design seems different

then most blogs and I’m looking for something unique.

P.S My apologies for being off-topic but I had to ask! https://Vander-Horst.nl/wiki/User:GildaFilson002

As the admin of this website is working, no hesitation very shortly it will be renowned,

due to its feature contents. http://Cloud-dev.mthmn.com/node/181762

If you desire to grow your experience just keep visiting this

web page and be updated with the most up-to-date news posted here. http://saju.Codeway.kr/index.php/User:MoraCrowley9830

If some one desires expert view on the topic of running a blog after that i advise

him/her to visit this weblog, Keep up the fastidious job.

I visited several web pages but the audio quality for audio songs present at this site is actually marvelous.

Hi! I’ve been reading your web site for a while now and finally got the bravery to go

ahead and give you a shout out from Houston Texas!

Just wanted to tell you keep up the good job! http://Mastas.co.kr/xe/index.php?mid=Construction_VOD&document_srl=940227

If you’re looking to boost your online business, consider buying verified Amazon accounts.

These accounts come with a proven track record and can help establish your

credibility on one of the world’s largest e-commerce platforms.

Get started today and take your business to new heights!

My family all the time say that I am killing

my time here at web, however I know I am getting knowledge every day by reading such

nice articles. https://Brilliantcollections.com/aguaria-spa-56/

Are you tired of struggling to sell on Amazon? Look no further!

Buying verified Amazon accounts can save you time and frustration. With a ready-to-go seller account, you

can start selling right away and avoid the tedious verification process.

Don’t miss out on this opportunity to boost

your business and increase your profits!

If you’re looking to enhance your online business or

increase your presence on Amazon, buying verified Amazon accounts is a smart move.

These accounts come with a solid reputation and are ideal for sellers seeking a boost in their sales and credibility.

Don’t let the competition outshine you – invest in verified Amazon accounts

for a successful e-commerce journey.

Verified Cash App accounts offer a secure and convenient way to manage your finances.

With verified accounts, you can confidently send and receive money, make purchases,

and enjoy the benefits of a seamless digital banking experience.

Don’t miss out on the advantages, get your verified

Cash App account today!

Looking to buy verified Cash App accounts? Look no further!

Our reliable service offers verified accounts with added security and convenience.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to simplify your financial

transactions. Purchase your verified Cash App

account today!

Excellent pieces. Keep posting such kind of information on your site.

Im really impressed by your site.

Hello there, You have done a great job. I’ll definitely digg it and in my opinion suggest to my friends.

I am sure they’ll be benefited from this website.

It’s really a great and useful piece of info.

I am glad that you just shared this useful information with us.

Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing. https://okniga.org/user/GordonEggleston/

I have read some excellent stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting.

I surprise how so much effort you put to make such a excellent informative site. https://Trans.Hiragana.jp/ruby/http://cloud-dev.mthmn.com/node/195640

you’re actually a excellent webmaster. The website loading pace is amazing.

It kind of feels that you are doing any distinctive trick.

Also, The contents are masterwork. you have performed a magnificent job on this matter! http://www.Diywiki.org/index.php/User:KashaOgilvie117

Remarkable! Its genuinely amazing piece of writing, I

have got much clear idea concerning from this article. https://isotrope.cloud/index.php/User:CharlotteDuncomb

Hey! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any trouble with hackers?

My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing months of hard work due to no

backup. Do you have any methods to protect against hackers? http://Cloud-Dev.Mthmn.com/node/182514

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was great.

I don’t know who you are but definitely you are going to a famous blogger if you aren’t already 😉 Cheers! http://eldoradofus.Free.fr/forum/profile.php?id=187306

Buying a verified Binance account has numerous benefits. It provides a hassle-free and secure way to trade cryptocurrency on one of

the leading exchanges. With a verified account, users

can enjoy higher withdrawal limits, increased security features,

and access to advanced trading options. Don’t miss out

on the advantages of owning a verified Binance account.

Having a verified Binance account can provide numerous benefits, such as

increased security and higher withdrawal limits. Don’t waste time waiting for verification, buy a verified Binance

account today and gain access to the world of cryptocurrency

trading with peace of mind. Stay ahead of the game and maximize

your potential profits with a trusted and verified Binance account.

Nice blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere?

A design like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make

my blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your theme.

Many thanks http://Www.sl860.com/comment/html/?241064.html

Are you looking to buy a verified Binance account?

Look no further! Buying a verified account not only ensures a secure and hassle-free trading experience but

also gives you access to advanced features and higher withdrawal limits.

With a verified Binance account, you can trade with confidence and enjoy the full benefits of this popular cryptocurrency exchange.

Don’t miss out on this opportunity, purchase your verified Binance account today!

Hi there everybody, here every person is sharing these kinds

of know-how, therefore it’s pleasant to read this webpage, and I used to pay a quick

visit this website every day.

Are you looking to buy a verified Coinbase account? It’s important to exercise caution when buying such accounts as it raises reliability and security concerns.

Make sure to do thorough research, understand the risks involved, and ensure the legitimacy of the

seller before making any transactions. Protect your investments and choose wisely!

This paragraph gives clear idea in support of the new people of blogging, that truly how to

do blogging and site-building. https://Illinoisbay.com/user/profile/6120414

I could not resist commenting. Well written! http://Luennemann.org/index.php?mod=users&action=view&id=324604

Looking to advertise on Bing? Buy a verified Bing Ads account to jumpstart

your online marketing efforts. Gain access to Bing’s vast audience and reach potential customers.

Advertise with confidence knowing your account has been verified

for authenticity and credibility. Boost your business today with a verified Bing Ads account.

Do you have a spam problem on this blog; I also am a blogger, and I was

curious about your situation; we have developed some nice

practices and we are looking to exchange methods with other folks,

be sure to shoot me an e-mail if interested.

I am curious to find out what blog system you’re using?

I’m experiencing some minor security issues with my latest site and I’d

like to find something more safeguarded. Do you have any

recommendations? http://www.healthcare-industry.sblinks.net/out/americanos-2/

If you’re new to the world of cryptocurrency trading and want to get started on Binance, it’s important to ensure your

account is verified. Buying a verified Binance account can simplify the process and save time.

With a verified account, you can trade larger volumes and access various

features easily. So, consider buying a verified Binance account to kickstart your trading

journey efficiently.

Howdy, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just wondering if you get a lot

of spam comments? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can suggest?

I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so

any support is very much appreciated. https://Rnma.xyz/boinc/view_profile.php?userid=1301276

That is really attention-grabbing, You are a very professional blogger.

I’ve joined your rss feed and look ahead to in search of more of your great post.

Also, I have shared your site in my social networks

If some one needs to be updated with hottest technologies

therefore he must be go to see this web page and be up to date every day. https://napiri.com/design_works/268717

Howdy! Someone in my Myspace group shared this site with us so I came to take a look. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Great blog and amazing design and style.

Buying a verified Binance account can offer a multitude of benefits.

It ensures a hassle-free registration process, guarantees top-notch security features, and allows access to a wide range of trading options.

With a verified account, investors can confidently

navigate the cryptocurrency market. Don’t miss out on these advantages, get your verified Binance account today!

Buying a verified Binance account can provide numerous advantages for cryptocurrency traders.

With a verified account, users can access advanced features,

higher withdrawal limits, and enhanced security measures. Additionally, it allows seamless trading across multiple cryptocurrencies.

Overall, purchasing a verified Binance account simplifies the trading process and boosts the overall trading experience.

Hi there, I discovered your site by way of Google whilst

looking for a similar matter, your site came up, it appears good.

I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hello there, simply turned into aware of your blog thru Google, and located that it’s really informative.

I’m going to watch out for brussels. I will appreciate for those

who continue this in future. Many other people will probably be benefited out of your writing.

Cheers! https://Readukrainianbooks.com/user/LucindaStoddard/

If you are serious about trading on Binance, it is wise to buy a verified account.

Verified accounts offer enhanced security features and higher transaction limits, ensuring a smooth

trading experience. With a verified Binance account, you can have peace of mind as

your funds are better protected. Get your verified Binance account today and unlock the potential of crypto

trading!

Excellent article. I certainly love this website. Stick with it!

To buy a verified Binance account, ensure you choose a reputable seller who

offers genuine accounts. Verified accounts grant you higher withdrawal limits, enhanced security,

and access to additional features. Consider the seller’s reviews, prices, and customer support before making a decision. Safeguard your investment

by taking the necessary precautions when purchasing a verified Binance account.

Looking to buy a verified Binance account? Ensure a

hassle-free trading experience with a trusted and verified account from Binance.

Enjoy a secure platform with enhanced features and faster withdrawals.

Buy your verified Binance account today and take your trading to

the next level!

Buying a verified Stripe account can be a game-changer for online

businesses. With a verified account, you gain access to a secure payment gateway that boosts your credibility, streamlines transactions, and ensures customer trust.

Invest in a verified Stripe account today and take your business to new heights!

Buying a verified Stripe account can be a game-changer for businesses wanting to accept online payments effortlessly.

With a verified account, one gains credibility, priority support,

and reduced payment processing delays. Explore the benefits and enhance your business by securely purchasing a verified Stripe account today.

Buying a verified Stripe account can offer numerous benefits for businesses.

With a verified account, you can securely accept

online payments, enhance customer trust, and streamline

your payment processes. Don’t miss out on this opportunity, buy a verified Stripe account

today!

Are you a business owner looking to accept online payments

seamlessly? Stop worrying about lengthy verification processes –

buy a verified Stripe account today! With a verified account, you can start

processing payments immediately, saving time and avoiding any unnecessary

hassle. Boost your business with this convenient solution now!

These are actually wonderful ideas in regarding blogging. You have touched some nice things here.

Any way keep up wrinting. https://Trans.Hiragana.jp/ruby/http://cloud-dev.mthmn.com/node/214322

Purchasing a verified Binance account has many benefits.

Trading cryptocurrencies becomes significantly easier,

as there’s no need to go through the tedious

verification process. Plus, upper limits on withdrawals are higher.

A verified account also offers an extra layer of security.

It helps prevent theft and fraudulent activities since the account is already linked to one’s personal name and information.

But remember, always buy from a trusted source to avoid discrepancies.

Buying a verified Binance account is an investment towards a smoother crypto-trading journey.

A verified Coinbase account offers a secure platform to buy and sell cryptocurrencies.

With features like added security measures and higher transaction limits, a verified

account ensures a smooth and reliable trading experience.

Take advantage of the benefits of a verified Coinbase account today!

Buying a verified Coinbase account is advantageous for those entering the world of cryptocurrencies.

With enhanced security and access to various features, it

provides a seamless experience. A verified account saves time on the verification process and offers peace of mind.

Invest wisely and pave the way to a successful crypto journey with

a reliable Coinbase account.

What’s Going down i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It absolutely useful and

it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to contribute & assist other customers like its aided me.

Great job. http://s741690.ha003.t.justns.ru/index.php?subaction=userinfo&user=CeceliaReeves

Its such as you read my mind! You appear to understand so

much approximately this, such as you wrote the book in it or something.

I feel that you simply could do with a few % to pressure the message house a little bit, however other

than that, this is great blog. An excellent read.

I’ll definitely be back. http://www.Zjxsnj.cn/comment/html/?47831.html

You actually make it seem so easy with your

presentation but I find this matter to be really something that I

think I would never understand. It seems too complicated and very broad for me.

I am looking forward for your next post, I’ll try

to get the hang of it! https://luxuriousrentz.com/plancher-vinyle-laval-st/