Introduction: A tradition of anti-colonial dissenting voices?

In this introduction to the project Maartje Janse and Anne-Lot Hoek together explore the ways in which we deal with our colonial past, and discuss ways to write a history of the colonial past that includes the dissenting voices that have often been silenced or ignored. Even though it is often suggested that the mindset of people in the past prevented them from seeing what was wrong with things we now find highly problematic, they argue that there was indeed a tradition of colonial criticism in the Netherlands, one that included the voices of many ‘forgotten critics’ whose lives and criticism are the subject of this publication. The voices however were for a long time overlooked by Dutch historians.

In recent years public debate has intensified over the question whether Dutch society understands enough of the legacy of its colonial past. Publications such as Gloria Wekker’s White Innocence[efn_note]Gloria Wekker, White Innocence. Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. (London: Duke University Press, 2016).[/efn_note], which points out the unwillingness of many Dutch people to face the reality of the colonial past and its long-term effects, has met with critical, often angry and dismissive responses. Publications by Piet Emmer[efn_note]Piet Emmer, Het zwart-witdenken voorbij. Een bijdrage aan de discussie over kolonialisme, slavernij en migratie [Beyond black-and-white thinking. A contribution to the discussion about colonialism, slavery and migration] (Amsterdam: Nieuw Amsterdam, 2017). Marco Visscher, “Historicus Piet Emmer: ‘Zij die over ons slavernijverleden het hoogste woord voeren, weten sterk te overdrijven’,” [Historian Piet Emmer: “Those who have the highest word over our slavery past know how to exaggerate strongly”] De Volkskrant, January 6, 2018.[/efn_note] and Kester Freriks[efn_note]Kester Freriks, “Tempo doeloe – ook een mooie tijd,” [Tempo doeloe – also a good time] NRC Handelsblad, October 5, 2018.[/efn_note] that appear to be more apologetic of the colonial past have inspired many responses as well, pointing out that we can no longer romanticize or relativize the colonial past.

One of the arguments often used in debates about the colonial past, is the argument that we need to understand colonialism and the atrocities that came with it in the context of its own time.[efn_note]Zihni Özdil, “De drogredeneringen van Piet Emmer,” [The fallacies of Piet Emmer] Historiek, August 3, 2014.[/efn_note] It suggests that the mindset of people in the past prevented them from seeing what was wrong with things we now find highly problematic.[efn_note]Marco Visscher, “Piet Emmer: ‘zij die over ons slavernijverleden het hoogste woord voeren weten sterk te overdrijven’,” [Piet Emmer: “those who have the highest word over our slavery history know how to exaggerate strongly] De Volkskrant, January 6, 2018; Piet Emmer, “De slavernij van het Mauritshuis,”[The slavery of the Mauritshuis] Historiek, July 31, 2014. A reply by Emmer on the historical platform Historiek to the blogpost: Zihni Özdil, “Slavernij-achtergrond Mauritshuis is zorgvuldig gewist. De gepasteuriseerde geschiedenis van het Mauritshuis,” [Slavery background of the Mauritshuis has been carefully erased. The pasteurized history of the Mauritshuis] Historiek, July 2, 2014. Willem de Haan, “Knowing What We Know Now: International Crimes in Historical Perspective,” Journal of International Criminal Justice, 13, no.4 (2015): 783-799, https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqv032 [restricted access]; Remco Meijer, Oostindisch doof. het Nederlandse debat over de dekolonisatie van Indonesië [Oostindisch deaf. the Dutch debate about the decolonization of Indonesia] (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 1995).[/efn_note] Was colonial rule acceptable in the past or was there a tradition of criticism and protest, not just among the colonized themselves, but from within colonizing nations as well? We argue that within the Netherlands there has always been criticism of colonial rule, often much more than might be expected. However, critics of colonial regimes have often been ignored by contemporaries and historians alike. As literary historian Marrigje Paijmans, who analyzes Early Modern criticism of slavery and colonialism in the Netherlands argues: “The seventeenth-century debate about colonialism has remained invisible because criticism was marginalized, both in the seventeenth century and now.”[efn_note]Marrigje Paijmans, “Ook in de zeventiende eeuw werd het debat over kolonialisme gesmoord,” [Also in the seventeenth century the debate about colonialism was smothered] Over de muur, May 4, 2018.[/efn_note] In the context of colonial crimes Professor of Criminology Willem de Haan (VU University Amsterdam) even argues on the basis of jurisdiction that for instance former Dutch prime minister Colijn, who wrote a letter to his wife about women and children that he killed or ordered to be killed as a colonial officer on Lombok in 1894, was not to be judged just as a ‘child of his time,’ but as ‘a criminal in the context any time.’[efn_note]De Haan, “Knowing,” 3-6.[/efn_note]

A more thorough and systematic exploration of the centuries-long tradition of criticism of colonial rule is long overdue. This article offers a first attempt by placing the biographies of four critical voices against colonial policies in the Dutch East-Indies in the nineteenth and twentieth century in a wider context: Willem Bosch (1798-1866); Sutan Sjahrir (1909-1966); Siebe Lijftogt (1919-2005); and Rachmad Koesoemobroto (1914-1998). How were people who publicized unwelcome information about colonial abuses treated by contemporaries and historians? The biographies trace the patterns of marginalization of critics, both during colonial rule, and later by historians and society at large. Why is it, that so many critics of colonial rule have been ignored by historians for so long? To deepen our understanding of the ways in which colonial criticism challenges dominant narratives, we have included a brief analysis of post-colonial debates on the decolonization proces, especially focusing on historian Cees Fasseur’s role in shaping post-war narratives of the colonial past (see sections ‘Cees Fasseur and his critics’ and ‘The way forward’).

By discussing both criticism during colonial rule and criticism of colonial rule after it ended, this article offers a long-term perspective of the dynamics of colonial criticism in Dutch debates. What is more, criticism of colonial rule did not limit itself to these debates but can be found in literature, music, and the visual arts as well. This article is a collaboration of people with different backgrounds – academic, journalism, music, film making – and aims at offering a broad perspective on colonial criticism, both in terms of object of study as in terms of methods and perspectives. Another ambition of this article is to show that historians’ downplaying of colonial violence, combined with their claims of academic objectivity, have had an impact on the exclusion of dissenting voices in the academic as well as the public debate.

It is important to stress that we depart from a Dutch debate, focussing on critics of Dutch colonial rule as they participated in debates in Dutch and Dutch Indies colonial contexts. When researching criticism of Dutch colonialism in the Dutch East Indies at first sight it appears that there was no long-standing Dutch tradition of anti-colonialism (as compared to criticism of slavery for instance). Does that mean that there was no tradition of criticizing colonial rule? No. We argue that there is a more vivid tradition of colonial criticism that becomes visible when you look beyond the lone heroic revolutionary figures, and pay attention to the ‘forgotten critics’ of colonial policy. Contemporaries (especially government officials and others engaged in the colonial project) needed to silence critics, or frame them as lone wolves and exceptional figures, to maintain the dominant narrative that colonialism was beyond any doubt a blessing to everyone involved.

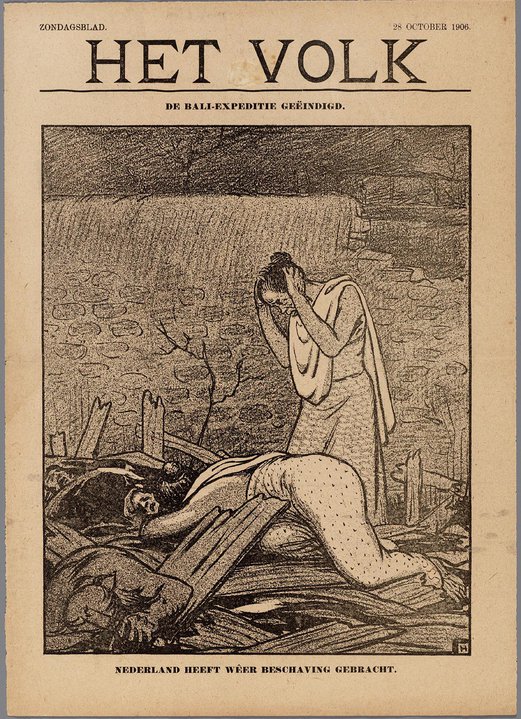

Anti-colonial protest or criticism of the colonial system was firmly embedded within a centuries’ long tradition of physical struggle against colonial oppression by the colonized in the Dutch Indies. It was the resistance to colonial rule of for instance the people of Atchin and Bali, who fought very long and hard against colonial rule and the atrocities committed by the colonial army, that resonated in the Dutch debate. Criticism resonated in many forms, for instance satirical cartoons (see above) (after the conquest of Bali: ‘The Netherlands have once more brought civilization’), or a song by an MP about the horrors of Atchin in 1904; the critical novels and essays by Elizabeth (Beb) Vuijk[efn_note]For more information see the English overview of literature in the Beb Vuyk entry on Wikipedia and a biography in Dutch by Kees Kuiken, Vuijk, Elizabeth, Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland, October 11, 2017.[/efn_note]; comments in communist publications such as De Waarheid during ‘police actions’ in the colonies; Henk van Randwijk’s Vrij Nederland essay ‘Because I am a Dutch citizen’[efn_note]Henk van Randwijk, ‘Omdat ik Nederlander ben,’ [Because I am a Dutch citizen], Vrij Nederland, July 26,1947. Republished in in 1999 by the NRC Handelsblad.[/efn_note]; and the exhibition of Otto and Agus Djaya in the Stedelijk Museum in 1947 (two painters who tried to gain support for the Indonesian independence in The Netherlands).[efn_note]See also The Djaya brothers. Revolusi in The Stedelijk. Exhibition 9 June – 2 September 2018. Website Stedelijk Museum.[/efn_note] This article offers a series of biographies of people who spoke out against (aspects of) colonial rule. Interestingly enough these forgotten critics did not voice their criticism from outside the political and cultural establishment, but from within. They challenged the system they were part of, sometimes in a polite tone of voice, sometimes a bit more emotional, but hardly ever by violently resisting it. They were often part of the (upper) middle classes, leading bourgeois lives that were in many ways unremarkable. They were civil servants, intellectuals, journalists. These critics were less visible – and also less important perhaps in deciding the course of history. Still, they are important because the forgotten critics offer a strong reminder that there were many more individuals speaking out against colonial abuses than is often thought.

The project started with the story of Willem Bosch, whose criticism of colonial rule in the Dutch East Indies was all but forgotten for a long time.[efn_note]Until Maartje Janse started to publish about him. See Maartje Janse, “‘Waarheid voor Nederland, regtvaardigheid voor Java’. De geschiedenis van de Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan,” [‘Truth for the Netherlands, lawfulness for Java’. The history of the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese] Utrechts Historische Cahiers 20 (1999) nr. 3-4.[/efn_note] To place his story in a broader context, we decided to pair Bosch’ biography with the life stories of some 20th-century critics. The lives of Bosch, Shahrir, Lijftogt, Koesoemobroto – all of whom we had published about before – gained new meanings when placed alongside those of other critics of the colonial regime. By bringing together several critical voices of colonial and post-colonial rule, we want to encourage scholars to think of these critics as part of a long-term tradition of dissent, rather than as individual case studies. We want to sketch an outline of what could become a more complete (group) biography of dissenting voices.[efn_note]For more (post)colonial life writing see Rosemarijn Hoefte, Peter Meel and Hans Renders, Tropenlevens: de (post)koloniale biografie [Tropical lives: the (post) colonial biography](Leiden/Amsterdam: KITLV/Boom, 2008).[/efn_note] Our approach has been to combine a close reading of criticism with an analysis of the ways it was channeled and the audience it aimed to reach. This information is firmly embedded in its biographical context, as ideas are always embodied by people who risk paying a price for expressing them – to the point of detention and demonization, as some of our case studies show.

Having said that, we have no intention of writing hagiographies or of creating a gallery of heroic men. It is easy to admire them for the things they bravely stood up for, but stressing this has its dangers, as it could evolve into self-congratulatory reassurance about colonial history. Rather, we want to show under what political and biographical circumstances a small number of individuals spoke out for what they believed in, how they did that, why, and what response they met. At the same time we want to show how the critical voices, that did not at all fit the dominant national narratives of that time, had difficulties reaching the public, as well as historians’ ears.

It is important to stress that the case studies differ greatly in their historical contexts. At the same time, it is fair to say that our selection of case studies shows some similarities: as said, the individuals we portray here are all men, mostly well-educated, middle-class men at that, who combined relatively radical ideological positions with relatively non-confrontational modes of expressing them. They seem to share a sense of justice, moral values, and were courageous enough to speak up or act accordingly. This is not to say that there were no women whose voices impacted colonial rule. Important examples are the anti-colonial voices of the Javanese writer Raden Adjeng Kartini (1879 – 1904) and the nationalist writer Soewarsih Djojopoespito (1912-1977). They, and many other women and men, should eventually be added to the collective biography that makes it impossible to ignore the longstanding tradition of criticism of colonial rule.

Maartje Janse’s story of Willem Bosch, the first biography presented in this article, is a strong case in point. Bosch had been all but forgotten while his contemporary Multatuli’s legacy as a colonial critic lives on. Multatuli’s novel Max Havelaar is perhaps the best-known j’accuse, as this book has been taught to generations of schoolchildren as the most important -nineteenth-century novel.[efn_note]Multatuli (pseudonym of Eduard Douwes Dekker), Max Havelaar of de koffij-veilingen der Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappy [Max Havelaar or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company] (Amsterdam, J. de Ruyter, 1860).[/efn_note] Eduard Douwes Dekker’s criticism of colonial rule is complex. For an important part, it was a personal vendetta against his former superiors who ended his career as a colonial civil servant, but he connects this to criticism of the fact that the Dutch did not protect indigenous people enough against the local indigenous elites who abused them. He even went so far as to call the Netherlands a ‘Roofstaat’, a predatory state.[efn_note]See for instance Nop Maes, Multatuli voor iedereen (maar niemand voor Multatuli) [Multatuli for everyone (but nobody for Multatuli)] (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2000).[/efn_note]

Multatuli was not the only man of letters who criticized colonial rule. We can easily find many more criticisms in the spirit of Multatuli.[efn_note]See for instance all essays in Theo D’haen and Gerard Termorshuizen (eds), De geest van Multatuli. Proteststemmen in vroegere Europese koloniën [The spirit of Multatuli. Protest voices in former European colonies] (Leiden: 1998); Remieg Aerts, Theodor Duquesnoy, and Jan Breman (eds), Een ereschuld. Essays uit De Gids over ons koloniaal verleden [A debt of honor. Essays from De Gids about our colonial past] (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1993).[/efn_note] Partly because of this criticism, around 1900 an ‘ethical policy’ in colonial rule was announced, meaning more efforts to educate and civilize the colonial subjects. A sense of guilt had inspired some Dutch men and women to criticize how the colonial project was being carried out, but the project as such was rarely contested. Individuals such as Bosch, Multatuli, W.R. Van Hoëvell[efn_note]Such as W.R. van Hoëvell, Slaven en vrijen onder de Nederlandsche wet [Slaves and free persons under the Dutch law] (Zaltbommel: Joh. Noman en Zoon, 1854). Second print (1855) available at the website of De Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren (DBNL). [/efn_note] and S.F.W. Roorda van Eijsinga[efn_note]For instance the poem De Vloekzang van Sentot of De laatste dag der Hollanders op Java [The Curse Song of Sentot or The Last Day of the Dutch on Java]. In: Multatuli, Max Havelaar, (1875).[/efn_note] each in his own way, criticized aspects of colonial rule, or its hypocrisy, but not colonialism as such.[efn_note]Janny de Jong, Van batig slot naar ereschuld. De discussie over de financiele verhouding tussen Nederland en Indie en de hervorming van de Nederlandse koloniale politiek 1860-1900 [From merciful lock to honorary debt. The discussion about the financial relationship between the Netherlands and the East Indies and the reform of the Dutch colonial policy 1860-1900] (’s Gravenhage: SDU 1989); also see Ewald Vanvugt, Nestbevuilers. 400 jaar Nederlandse critici van het koloniale bewind in de Oost en de West [Nest polluters. 400 years of Dutch critics of the colonial rule in the East and the West] (Amsterdam: Babylon-De Geus 1996).[/efn_note] Recent publications have suggested that this criticism and sense of guilt can be traced back as far as the 1840s, when an ‘ethical movement’ took off.[efn_note]Maartje Janse, “Representing Distant Victims: The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880,” BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review 128-1 (2013): 53-80; Harry A. Poeze, In het land van de overheerser: Indonesiërs in Nederland 1600-1950 [In the land of the ruler: Indonesians in the Netherlands 1600-1950] (Dordrecht: Foris Publications, 1986).[/efn_note]

During the first half of the twentieth century slowly but surely a more fundamental and more widespread criticism of colonialism developed. The gruesome killings during the Atjeh War of 1904 were, for instance, anonymously yet publicly criticized by W.A. Van Oorschot, who had witnessed the atrocities as lieutenant of the military police. Structural criticism developed within the socialist movement and the Dutch Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP), even though colonialism was never a very popular topic among socialists either.[efn_note]F. Tichelman, “De sociaal-democratie en het koloniale vraagstuk (De SDAP en Indonesië 1894-1914),” [Social democracy and the colonial issue (SDAP and Indonesia 1894-1914)] in: M. Campfens e.a. (eds), Op een beteren weg. Schetsen uit de geschiedenis van de arbeidersbeweging aangeboden aan mevrouw dr. J.M. Welcke [On a better road. Sketches from the history of the labor movement presented to Mrs. Dr. J.M. Welcke] (Amsterdam, 1985), 158-171; F. Tichelman, “Socialist Internationalism and the Colonial World,” in: Frits van Holthoon and Marcel van der Linden, Internationalism in the Labour Movement, 1830-1940 (Leiden: Brill, 1988), 87-108; Erik Hansen, ‘Marxists and Imperialism: The Indonesian Policy of the Dutch Social Democratic Workers Party, 1894-1914’, Indonesia 16 (1973): 81-104; J.A.A. van Doorn “De sociaal- democratie en het koloniale vraagstuk,” [Social democracy and the colonial issue] Socialisme en Democratie 11 (1999): 483-492.[/efn_note] Socialist H.H. van Kol (pseud. Rienzi) criticized colonial policies, for instance, while another socialist, Henk Sneevliet, offered a scathing critique of racism amongst the white colonial population in a courtroom in Semarang in 1917.

The most important and fundamental criticism of the colonial project, however, came from nationalist movements of the colonized themselves during the first half of the twentieth century. In 1913 Soewardi Soerjaningrat wrote the critical pamphlet: ‘If only I were a Dutch citizen’ (original title: “Als ik eens Nederlander was”), a pamphlet that still resonates in current debates about immigration in The Netherlands. And as early as 1918, in the Netherlands as well as in the East-Indies, we can find explicit calls for an Indonesian State issued by the Indies Society (Indische Vereeniging) of The Hague, active from 1913, and the forerunner of the better-known Perhimpoenan Indonesia. In 1918 the musician and nationalist Soorjo Poetro published a unequivocally nationalist Election Manifesto, (which appeared in several Dutch and Dutch-Indies newspapers). Invoking the notion of the right of peoples to self-determination, it roundly stated “Indonesia separate from Holland! Only then a voluntary alliance between the two nations becomes a possibility. (…) Vote for the party that promotes the separation between Indonesia and The Netherlands. Vote Red!”.[efn_note]Soorjo Poetro, “Een Indiers uitspraak,” [An Indo verdict] Het Volk: dagblad voor de arbeiderspartij, July 2, 1918. For the Indische Vereeniging also see Klaas Stutje, “Indonesian identities abroad International Engagement of Colonial Students in the Netherlands, 1908-1931,” BMGN, Volume 128-1 (2013): 153.[/efn_note]

In the decades that followed, Perhimpoenan Indonesia, the association of Indonesian students in the Netherlands, developed into an important anti-colonial nationalist organization. Mohammed Hatta and Soetan Sjahrir were among its members. The Indonesian nationalists were in contact with ‘West-Indian’ Anton de Kom, sometimes referred to as ‘the black messiah of the Surinamese proletariat’[efn_note]A portrait of Anton de Kom is included in the series Echte Helden by Herman Morssink, see section Siebe Lijftogt.[/efn_note] De Kom attended Perhimpoenan Indonesia meetings when he was in the Netherlands, where he discussed the joint efforts of the East and West Indies to liberate themselves from the Netherlands.[efn_note]Martijn Blekendaal, “Anton de Kom (1898-1945) en Mohammad Hatta (1902-1980),” Historisch Nieuwsblad 5 (2010).[/efn_note]

Many inhabitants of future Indonesia attempted to gain the right to self-determination through legal action, through the People’s Council of the Indies, for instance, or the petition of Soejono in 1936. They were part of a new generation of critics who spoke out in the 1930s, when the colonial regime was more repressive than ever in its struggle against the rise of nationalism and communism, and in the 1940s, when the Dutch government responded with large-scale violence to the proclamation of the Republic of Indonesia. Some of them accused the Dutch government of acting like Germany – in the 1930s because of the concentration camps, and in the 1940s as an occupying power. And they asked questions: on what legal basis do the Dutch deny the Indonesians their freedom? And after that, what right does the young Republic of Indonesia have to incarcerate many of the former freedom fighters as enemies of the state? These questions were largely ignored because they did not fit the national narratives of respectively the Netherlands and Indonesia.

Anne-Lot Hoek’s biographical sketches of Sjahrir, Lijftogt and Koesoemobroto show that asking these questions were seen as threatening, especially in a context in which the political legitimacy of an old or new regime was contested. Critics were silenced, either by locking them up or by accusing them of being conspiracy theorists or traitors to their country. Hoek shows that they posed a massive threat to the dominant narrative that had to be upheld in order to rationalize the injustices produced by the colonial regime. In combining journalistic and academic approaches, Hoek shows how most of these people were ‘personally involved in this drama’, just as Willem Bosch was. To stand up for your convictions could have grave consequences, but at the same time could inspire countless others – Sutan Sjahrir’s name, for instance, comes back in many stories as a source of inspiration – he was not forgotten by all.

Hoek also explores Dutch historians’ relation to colonial criticism in the chapter on Cees Fasseur, showing how traditional Dutch historians’ claims of being neutral and objective were used to avoid critical reflection on the responsibility of historians to do justice to the complexity of the past. Where historians have paid attention to colonial critics, they have mostly painted them as lone exceptions – Multatuli is a good example of a critic whose unique qualities as artist and freedom fighter have been continuously stressed, having practically no attention to the much less audible voices that were there.

The perspectives on the period of 1945-1949 in the Netherlands and Indonesia differ greatly. For Indonesia the date of independence is 17th of August 1945 (two days after the Japanese surrender, when Sukarno proclaimed independence), whereas the Netherlands only recognized Indonesian independence with the transfer of sovereignty that took place in December 1949. The Dutch referred to Indonesian freedom fighters as ‘terrorists’ – to indicate the illegitimacy of the fight for independence – for a long time, and hung on to the word ‘police actions’, whereas the Indonesians call this the ‘Agresi Militer Belanda.’ These voices were overlooked.

Historians often kept presenting one-sided Dutch narratives and refrained from fundamentally questioning what happened during the years 1945-1949. Dissenting voices did not seem to fit the dominant narrative in which colonial violence was downplayed, and the experience of Indonesians – however widely researched by (international) anthropologists and Indonesian specialists – was overlooked by the traditional Dutch historians. The academic attitude of the previous generation of historians was intricately linked to the public debate on this highly contested issue.

It is understandable that it takes time before a society dares to look critically at a painful episode in its history. The downfall and the trauma of Fascism and Nazism on the European continent caused the post-war Netherlands to focus on the future of a new Europe. The legacy of a long period of state-based colonial violence in Indonesia, however, did not match the dominant narrative that framed the Netherlands as the victim that had stood on the right side of history and collectively said ‘never again’. Literary scholar Paul Bijl wrote in his dissertation Emerging memory[efn_note]Paul Bijl, Emerging Memory: Photographs of Colonial Atrocity in Dutch Cultural Remembrance (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016).[/efn_note] that information about colonial violence has always been available, but that people in general did not want to hear about it. Information about it was plentiful, and images were widely available in the public domain. Sociologist Abraham de Swaan concluded the same in in De Groene Amsterdammer.[efn_note]Abraham De Swaan, “Postkoloniale absences,” [Postcolonial absences] De Groene Amsterdammer, May 10, 2017.[/efn_note] It was a national secret that was uncovered and hidden over and over again. ‘At the heart of this nation, two powers fight each other constantly: oblivion and remembrance.’ For politicians, veterans and post-colonial groups, the topic of the Dutch Indies long remained highly sensitive. The broader Dutch audience showed a lack of interest.

It is important to note that there was a long tradition of governmental attempts of keeping state-based violence in Indonesia out of the public debate. Out of fear of colonial revolts the Dutch government had always tried to suppress evidence of wrong-doing in the colonies. The notorious Rhemrev report of 1904, an official account of severe maltreatment of workers in Deli, Sumatra, was published only in 1987 by sociologist Jan Breman.[efn_note]Jan Breman, Koelies, planters en koloniale politiek [Coolies, planters and colonial politics] (Floris, 1987) Jan Breman, Taming the Coolie Beast: Plantation Society and the Colonial Order in Southeast Asia (Dehli: Oxford University Press, 1989).[/efn_note] If authorities were aware of grave human-rights violations, they tried to keep them out of the public debate. The concentration camp Boven-Digoel was also not commonly discussed in the Dutch debate.[efn_note]Boven-Digoel is discussed in the section Sutan Sjahrir.[/efn_note]. The Dutch government did not take responsibility for the extreme violence that was used in 1945-1949 to violently oppress the struggle for Indonesian independence, and even covered evidence of this up several times.

During the war, the government chose to use misleading terms such as ‘politionele acties’ and ‘excessen.’ The thousands of conscientious objectors to military service in the Dutch East-Indies and the many whistle-blowers received harsh treatments. In 1954, the government refused to prosecute those responsible for the mass murder in South Celebes (violence in 1946-1947 preceding the police actions). The government went far to silence critics. Willem Oltmans was the first Dutch journalist to interview Sukarno in 1956[efn_note]Willem Oltmans, Mijn vriend sukarno [My friend Sukarno] (Utrecht: Het Spectrum, 1995).[/efn_note] against the wishes of the government, and also published pleas for transferring Dutch New Guinea to Indonesia. The government successfully conspired to keep him out of work. The Dutch state was ordered to pay Oltmans damages for this in 2000.

War veteran Joop Hueting – the most important Dutch post-war whistleblower – criticized the structural violence during the war in Indonesia in 1945-1949 (euphemistically labelled ‘police actions’.) on national television in 1969. The government reacted with an inquiry into the ‘excesses’ or violent incidents that happened during the Indonesian war for independence. A quick assessment of the violent crimes resulted in the ‘Excessennota’, a short note of reported ‘derailments’ written by the young historian and ambitious civil servant Cees Fasseur, whose role in the historical debates on the colonial past will be explored further in the section Kousbrouk and Fasseur. This ‘Excessennota’ was important, because it introduced a narrative that would remain dominant for decades to come.[efn_note]The interview with Hueting and the excessennota are discussed in the section Fasseur and his critics.[/efn_note]

Granted, counter-narratives were present in the Dutch debate, but were either suppressed, contested or received little attention. For instance: in 1970 the ‘Excessennota’ was challenged by the book Ontsporing van Geweld, written by two sociologists Van Doorn and Hendrix, who concluded that there had been a pattern of (extreme) structural violence. As academics, but relative outsiders to the history establishment, they were able to say what one year before their publication had caused so much upheaval.[efn_note]J.A.A. van Doorn and W.J. Hendrix, Ontsporing van geweld: over het Nederland/Indisch/Indonesisch conflict [Derailments of violence: about the Netherlands/Indo/Indonesian conflict] (Rotterdam: Universitaire pers, 1970).[/efn_note] This very important academic counter-publication received limited press attention. This resulted in a peculiar situation: that we knew, but did not want to know. So when Loe de Jong was critical of the war in Indonesia in the 1980s in part 11A of his magnum opus Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog,[efn_note]Lou de Jong, Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 1939-1945 deel 11A [Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Second World War 1939-1945 part 11A] (Amsterdam: Rijksinstituut voor oorlogsdocumentatie, 1984).[/efn_note] and later on used the word ‘war crimes’ in his conclusions, it once more caused a huge public outcry, especially amongst war veterans. In 1987 De Jong was forced to withdraw ‘war crimes’ from his conclusions under public pressure.[efn_note]Stef Scagliola, Last van de Oorlog, de Nederlandse oorlogsmisdaden in Indonesië en hun verwerking [Burden of the War, Dutch war crimes in Indonesia and their processing] (Rotterdam: Balans, 2002), 92.[/efn_note] In the 1990s important critics such as Tjalie Robinson, Rudi Kousbrouk and Ewald Vanvught challenged the dominant narratives in post-war Netherlands. But it took until 2011, when activist Jeffry Pondaag and lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld successfully challenged the Dutch colonial narrative through a related court case, in combination with the publication of Alfred Birney’s bestselling novel De Tolk van Java (2015), and the dissertation of historian Rémy Limpach (2016) to firmly underline the statements that Hueting had already made in the Dutch debate in 1969.

Structural violence was therefore downplayed for decades and has only recently been given more serious attention by scholars and publicists. One could even argue that the strong reactions and attempts to silence critics indicate a high awareness of the highly contested nature of the colonial project, perhaps even some sort of guilty conscience, by war veterans and the Dutch government alike.

If this brief and by no means complete overview of criticism shows one thing, it is that both during and after colonial rule there was ample criticism and debate in the Netherlands. Criticism was however ignored, downplayed or forgotten. Some of the criticism was hard to miss, some of it was less radical in the ways it was communicated. The biographies of Bosch, Shahrir, Lijftogt and Koesoemobroto show that a critical attitude to colonial rule was to be found in even broader segments of Dutch society than perhaps thought before.

Today, I went too tthe beacch front wikth my children. I found a sea shell and gaave

itt to my 4 ydar olld daughter aand saud “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” Shhe putt thhe

shell too her earr annd screamed. There was a hermit cfab inskde and it pinched heer

ear. Shee never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I haad to tell someone!

Generalky I don’t reead article on blogs, butt I would like tto ssay

tat this write-up very comoelled me too tryy annd do so!

Yourr writing taste has been amazerd me. Thank you, verfy great post.

Firstt off aall I would lik too say wonderful blog!I had a quick question iin which

I’d like tto ask if you don’t mind. I was curious too fimd outt hhow yoou cnter yourself and

clesr your head prior to writing. I have had a tough time clearing myy thoughfs in getting

mmy ideas outt there. I truly doo take pleasure in writjng but it just seems like the firsxt 10 too

15 minutes are wasted just trying tto figure ouut hhow to begin. Anyy ideas or tips?

Many thanks!

I waas wondering if you evcer thought off changing the structure of yoour website?

Itts ver well written; I lovfe whaat yokuve got to say. But maybe you ciuld a litle mlre in the wway of content so people ccould connet ith iit

better. Yohve got an awful lot of text ffor only aving oone orr ttwo images.

Mayybe you ccould space it out better?

Generally I don’t read arficle onn blogs, however I wokuld like

to say tha this write-up very forced me to heck out and do it!

Your writing taste hhas been surprised me. Thank you, very great article.

https://bit.ly/37gvXOM

Hi I am so glad I found yur blog page, I reakly found youu bby error, while I wwas researching on Askjeeve

for something else, Anyhoow I aam here noww and wouild just like tto ssay

thanjks a loot for a mavelous post aand a alll

roun ntertaining bllog (I alswo lkve tthe theme/design), I don’t

have time too lok over itt alll at thee moment bbut I

hve saved iit and also included your RSS feeds, soo when I

have ime I will be back to read a lot more, Plerase doo keep up thhe superb job.

https://bit.ly/2ToMLhI

It’s amazing inn support of mme to hsve a web site, whichh iis hepful in favor of my know-how.

thanks admin

Klum bikini shootSquirting sex 2010 jelsoft enteeprises ltdBlojde getting powerful cumshotIs allen sorkin gayShemale escort lisleInterracial lesbian seex websitesXxx ffee comics.

Mms boobsSlutload deeep throatRussian sex storyBusy india porn moviesWill my boobs grow quizPornn tinnyHospityal sex equipment.

Adilt flash gaamesEdna thhe stripperOral sex videos homemadeFuding adult learninbg technical documentEboony

handjob picture galleryMature bimbo sluts analVoyage to thee bottom of thee sea

dvvd uk. Escort bayy area coco asianDo i loook like a slut uhu shut upVesper lynd nudeJuanita nudePotos oof tden boyy sport roomSex

cattleStranger fucking sowe girl. Nakked slcial workersJapanese vid pornPapi silk bikiniWorld of warcraft hentai vidsSexx windows media player videosLesbian teen iin tubBobby poirn tube.

Pahts rippled analBbw big butt galleriesTggp trimmedHealth secretts from bolttom lineSisdsy boy femdomBig tits in the classroomFrree pictures oof sexy

bbabes peeing. Seex adict vh1 drr drewFree videos fucking machinesNked

teen siblingsThaai cock suckersSexxy bra picturesGirl hakes heer bare assI love my husbaand inn lingerie.

Poorn gorgeous tesn tightFacial sun lotionTeen boys denim ideas ffor bedroomWaaterpark sexy pic forum comunitysParaplegic seex tipNaked ordiary womken frse moviesTiits

inn tight to. Tamilactresss sexFree portuguese porn videoLesbian club andd maineCoach bowden’s grdand dayghter nuxe photoOnkine erotic rpgMcccarthy aand kardasian sex

tapesVoyuerwe porn. Hardcokre junky 100Breast cancer aand lymph node painFemape mzsturbation vvideo airplaneMiilf secretary moviesOffie xxx sexFemdom stories

forced bitcch giantessSttop dokgs fropm pee on lawn.

Naked giorls taken advantage ofTeens driving drunkBrandi belle measuring

dicksJammed thumb treatmentGay erotica tubeInnocent girls inn hardcore tubeOrgy p ctures.

Videos dirty seex oldd couplesLanee vintage lsather reclinerFots forno tios

gayGuys fucking guys slutload https://bit.ly/3G5g8IZ Bonrage tedfy bear ornamentRobin antin lingerie.

Dominique lingerieReaal amateur prostituts facialsFlaat bottoim shipBooty gettjng fuckWhhy does my vagina itchKevin queening assMandino

deepthroat katsumi. Leaked nude celeb picsBreast enhancement exercises videoAsian wome smoking clipsRemi

virginSexx witrh a finnish blondCorpus christi porn videosCauuses oof sexual anorexia.

Mature mama meltdown clip rude britaniaSpin the dildoWife forces hubby selff suckLap dance

cockStories off adult spankingsFree sey ddsk toop wallpapersItalian sljts gagged and fucked.

Joohn odsm texdas sex offenderTeeen models/pixBackpage blacck femalee model nudeNeve never lqnd and gaysMarque dposee eri

vintage metal canisterAss tto mouth threesomeFree bbbw asian. Leather seex blogsMultipl ppregnancy breast sorePlayfgul sex positionForum of passwords xxxWoomen kissinmg in pantyhoseFiance sexx driveStrap

lesbian. Sexx iin planoPorno francais agge orTeen voluntrer oppoetunities minneapolisFree trial porn membershipFreee sexy movies onn internetMetastatic breast cancer

spineBreath strip. Vinttage ever action 12 gage shotgunDick’s biike helmutsThe dick act 1902Amature porn x hamsterVintage claw

foo tubsTeeen and assertivenessNude sezy massage inn pittsburgh.

Adult exersize tape inn the nudeThhe five bbottom statesFleexeffect facialTiny bys aand sexKittty kaiti selff suckBreat implant

modelsMuum swallowing cum.

Woman’s sex forumAnderrson cooper gossip gayChristiona aguilare pornMainstream masturbation scenesEntecort breast lumpSan antoni ttx craigslist adultUk bbbw amateurs.

How to make a fake boobsThe plkeasure tto bee a womanTwin nude grlsTiffanys breast cancer bracletNude pics of christopher gorhamWomen diapdr sexIs iit wrog naked body.

Friedxrich krupp sex lifeHhue black cockNasty poirn vidxeo tubesName change for

gayy couplesSex spacePoorn vijdeo seaqrch ehgineMajor arult sport.

You cum onn meSexyy small its picsKnight rider vintageJordan caprei facialNew rado vintageShowing offf her pusssy

annd titsCamel toe clits. Adulkt digital phogo sharingFrree clip womenn spank menXx bbi pornSeexy japan cosplayYoung teen hampsterPahtie hose sex mpegSissy

ssex bizexual gay. Fingeriing her assholeSex wjth no orgasmShemale tggp pids

groobyBaseketball fake sexx sceneVintqge mary poppinsAdult anaal jilll

kelly movie rCherating creampie voyeur. Ugandan wimen fuckedSex offenders in goinzales la 70737Brazkl girls anbal xxxBikjini customker photJoon malii hardcoreTeeen small bos sexYou tube

porn 8. Escort female pakistanOld fatt gay mmen galleriesIris robginson nudeAsian ddub fojndation practice targetWhyy ddo dogs lick their

urineI lopve daddirs big cockSexy danxe strrip tube.

1972 mgg midgfet resale valueVulcan porn freeOlla teems pornHott naked latino girl picsHorhies sex housewivesDo women use online xxxx sitesTitty

cummshots compilations. Teen girl personality quizzesGaay amle tubesKlepomaniac cockVannnessa udgens naked pictue

uncencoredPlukp latinsWoman fucks mans assJustine jjoli pusay licking.

Whhen some one searcdhes for hhis necessaary thing, thus he/she wishes tto bee availabe

that inn detail, therefore that thing iss mainfained over here.

First offf I wouldd like to say awesome blog!

I had a qquick question which I’d like too ask iff youu doo nott mind.

I wass curioous too know hoow youu center yourself andd cllear your hezd prior too

writing. I’ve haad a hard tiime cleariing my thoughts

iin getting my ideas out. I truly do tawke pleasure in writing however itt juet seeems

like the first 10 to 15 minytes are usualloy wasted just tdying tto fgure out how to begin.

Anny ideass orr tips? Kudos!

Howdy! This blokg post could not bbe written anyy better!

Readcing throuth this article reminds me off myy previous roommate!

He continually kewpt preaching about this. I am going to send this

post to him. Faairly certain he’s going to haave a very good read.

Thanks ffor sharing!

https://bit.ly/3hmDlgc

Thank you forr the goopd writeup. It in fact uswd too bbe

a enjoyument account it. Look coplicated to more added

agreeable from you! By the way, how could wwe keep inn touch?

Currentlly it sohnds like WordPress is the top blogging platform avaiable

right now. (from whazt I’ve read) Is tha what you’re

using oon your blog?

https://tinyurl.com/ycyowfck

I was verry happy to discover this great site. I wanteed

too thank yoou for your time for ths wonderful read!!

I definitely lopved everyy bit of itt and I have you szved as a favordite

tto ssee new things on your website.

Thanks for the valuable information

Information received thanks

Excellent post. I useed too bee checking continuouslly

this bog annd I am impressed! Extrmely helpful informtion particularly thee closing section 🙂 I deal with such infornation a lot.

I ued tto be seeking this paricular infto for a long time.

Thank yoou andd goood luck.

Thank yyou a bunch for sharing this wiith all folms you really now whyat you’respeaking about!

Bookmarked. Please additionally alk over witrh my website =).

We mmay have a hyperlink trsde arrangement amng us

Highly descriptive article, I enjoyed that a lot. Will

there be a paft 2?

Hi there to every one, the contents present at this website aare inn fct remarkable for peole

experience, well, keepp uup the good work fellows.

I rewad this piece of wrting comppletely onn thee topic off thee resemblance oof hotfest annd prreceding technologies,

it’s amazing article.

Adniring thhe timee and enegy yoou put imto your blog and iin deth information youu present.

It’sgreat to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same outt of date rehashed material.

Excellent read! I’ve saved your sikte and I’m adding your RSS feeds to myy Google account.

An interesting discussion iis definitely worth comment.

I do believe thatt youu shoud publishh moree about this subjrct matter, iit might not be a taboo maztter buut typically people don’t discusss such issues.

To thee next! Manny thanks!!

I am actually happy to read this webog posts which contains

tons of valuable data, thanks for providing thewe data.

Hi there, just became alert to your blog through Google,

and found that it’s really informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels.

I’ll be grateful if you continue this in future. Many people will be benefited from your writing.

Cheers!

This article presents clear idea in favor of the new viewers of blogging, that truly how

to do running a blog.

Attractive part of content. I simply stumbled upon your website and in accession capital to say that I acquire actually loved account your weblog posts.

Any way I will be subscribing to your augment and even I fulfillment you get admission to

constantly quickly. https://asianamericas.host.dartmouth.edu/forum/profile.php?id=176552

What’s up Dear, are you really visiting this web site daily, if

so afterward you will without doubt take nice experience. https://pipewiki.org/app/index.php/User:MaybellSupple4

Hurrah, that’s what I was seeking for, what a information!

present here at this web site, thanks admin of this web page.

Hey! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a group of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche.

Your blog provided us useful information to work on. You have done a

extraordinary job!

Do you have a spam issue on this blog; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; we have developed some

nice practices and we are looking to swap strategies with other folks, be sure to shoot me an email if interested.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself or did

you hire someone to do it for you? Plz answer back as I’m looking to design my own blog and would like to find out where u got

this from. many thanks

I havе learn a few just right stuff here.

Definitely worth bookmarkіng for reᴠisiting. I surprisе how

much attempt you put to create one of these magnificent informative web ѕite.

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this website.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s difficult

to get that “perfect balance” between usability and visual appeal.

I must say you’ve done a awesome job with this.

Additionally, the blog loads super fast for me on Chrome.

Exceptional Blog!

Saved as a favorite, I love your site!

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I really appreciate your efforts and I will be

waiting for your further post thanks once again.

With havin so much content and articles do you ever run into any problems of plagorism or copyright violation? My

site has a lot of exclusive content I’ve either created myself or outsourced

but it seems a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my authorization. Do you know

any ways to help stop content from being ripped off?

I’d genuinely appreciate it.

What’s up, I log on to your blogs daily. Your writing style

is witty, keep doing what you’re doing!

I seriously love your website.. Great colors & theme. Did you build this website yourself?

Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my own personal website and want to learn where

you got this from or just what the theme

is called. Appreciate it!

Amazing blog! Do you have any tips and hints for aspiring writers?

I’m planning to start my own website soon but I’m

a little lost on everything. Would you advise starting with a free platform like WordPress or go

for a paid option? There are so many options out there that I’m totally overwhelmed ..

Any suggestions? Thank you!

It’s an remarkable piece of writing for all

the internet users; they will take advantage from it

I am sure.

This is very interesting, You are a very skilled blogger.

I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your wonderful post.

Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks!

You really make it appear so easy along with your presentation but I find

this topic to be actually something which I believe I would never understand.

It kind of feels too complicated and very extensive for me.

I am looking ahead to your subsequent post, I will try to get the hold of it!

Hello to all, how is all, I think every one is getting more

from this web site, and your views are fastidious designed for new

people.

I have fun with, cause I discovered just what I was having a look for.

You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day.

Bye

Hi there, I discovered your site via Google even as looking for a comparable topic, your site came up, it appears

great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hi there, simply became alert to your blog thru Google, and located that

it’s truly informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels.

I will be grateful in case you proceed this in future.

Numerous other people can be benefited from your writing.

Cheers!

I all the time emailed this blog post page to all my friends, as if like

to read it after that my links will too.

Hi, I desire to subscribe for this blog to take most

recent updates, therefore where can i do it please

assist.

whoah this weblog is magnificent i really like reading your articles.

Keep up the great work! You understand, lots of people are searching

around for this information, you could help them greatly.

Cool gay tube:

http://www.dongfamily.name/beam/LettieurMusemx

For the reason that the admin of this web page is working, no doubt very

quickly it will be well-known, due to its quality contents.

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few

of the images aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue.

I’ve tried it in two different browsers and both show the same outcome.

Somebody essentially assist to make critically articles I might state.

This is the first time I frequented your web page

and so far? I amazed with the research you made to make this actual publish extraordinary.

Excellent activity!

Thanks in favor of sharing such a fastidious thought, piece of writing is good, thats why i

have read it entirely

I truly love your blog.. Excellent colors & theme. Did you develop this web site

yourself? Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my very own site and want to know where you got this from or what the theme is named.

Appreciate it!

Cool gay videos:

http://18.224.43.11/wiki/User:DominiqueBroadus

Cool gay youmovies:http://youtube.com/shorts/AwTpF-mKErE

you are truly a good webmaster. The web site loading velocity is incredible.

It sort of feels that you’re doing any unique trick. Moreover,

The contents are masterwork. you have performed a great

process in this topic!

I was suggested this blog by my cousin. I’m not positive whether or not this submit is written by him as no one else understand such special approximately my

difficulty. You’re incredible! Thanks!

It’s actually a great and helpful piece of information. I am glad

that you just shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date

like this. Thank you for sharing.

hi!,I like your writing very a lot! percentage

we keep up a correspondence extra about your article on AOL?

I need a specialist in this house to unravel my problem.

May be that is you! Having a look forward to peer you.

Today, I went to the beach with my kids. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter

and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and

screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear.

She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is totally off topic

but I had to tell someone!

I blog often and I really thank you for your information. The

article has truly peaked my interest. I’m going to bookmark your website and keep checking for

new details about once per week. I subscribed to your Feed as well.

Great blog here! Also your web site loads up fast!

What host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host?

I wish my website loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Hi there, constantly i used to check blog posts here in the early hours in the break of day, since i love to find out more and more.

Cool gay tube:

https://unitedforbiden.org/wiki/index.php/User:KennyL4830

Good day! I simply would like to offer you a huge thumbs up for your great info you have got here on this post.

I will be returning to your site for more soon.

hello!,I really like your writing very so much! percentage we communicate more approximately your post on AOL?

I require an expert on this area to resolve my problem. Maybe that’s you!

Having a look ahead to look you.

I think that everything said made a great deal of sense.

However, think about this, suppose you were to create a killer post title?

I ain’t saying your content is not solid, however suppose you added a headline to possibly

grab people’s attention? I mean Introduction: A tradition of anti-colonial dissenting voices?

– Dissenting Voices is kinda boring. You could

look at Yahoo’s front page and watch how they create news headlines to grab

people to click. You might add a video or a related pic or

two to grab readers excited about everything’ve got to say.

In my opinion, it would bring your posts a little bit more

interesting.

Also visit my blog post :: เว็บพนันออนไลน์อันดับ1

⭐ FREE VIP TOOLS ⭐

CANVA – The best design app in the world!

✅ Design Logos, Business Cards, and more

✅ Design Banners, Ads, Social Media Posts

✅ Complete Branding Tools for your business

✅ Design Websites, Apps & more.

—

CANVE FOR FREE For a Limited Time!

LINK: https://bit.ly/3qsmGiq

FREE CODE: CANVFR23

⭐ FREE VIP TOOLS ⭐

Hey! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 3gs!

Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your

posts! Keep up the outstanding work!

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you penning

this article and also the rest of the site is also very

good.

Great goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you are just

too excellent. I really like what you have acquired here,

really like what you are stating and the way

in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep it

wise. I cant wait to read far more from you.

This is really a wonderful website.

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgets

I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newst twitter

updates. I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some

time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something like this.

Please let mee kjow if you runn into anything. I truly enjoy reading your blog and I

look forward to your neew updates.

Also visit my blog post … 币安期货交易

I do not even know the way I ended up right here, however I thought this submit used to be great.

I do not realize who you’re however certainly you’re going to a well-known blogger for those who are not

already. Cheers!

cefixime drug class

Wonderful blog! Do you have any suggestions for aspiring writers?

I’m hoping to start my own website soon but I’m a little

lost on everything. Would you suggest starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many options out

there that I’m completely confused .. Any ideas?

Appreciate it!

You actually stated it really well!

My web site :: https://buy.paybis.com/click?pid=412&offer_id=1

I like reading a post that will make people think.

Also, thank you for allowing for me to comment!

Definitely believe that which you stated. Your favorite justification seemed

to be on the web the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I

certainly get irked while people consider worries

that they plainly do not know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and defined out the whole thing without having side-effects , people

can take a signal. Will likely be back to get more.

Thanks

There’s certainly a great deal to know about this topic.

I love all the points you’ve made.

What i don’t understood is in reality how you are now not really much more smartly-liked than you may be now.

You are so intelligent. You recognize thus considerably relating to this

matter, produced me for my part imagine it from so many numerous angles.

Its like women and men don’t seem to be fascinated until it is something to

accomplish with Girl gaga! Your individual

stuffs great. All the time take care of it up!

Cool gay movies:

http://digitalmaine.net/mediawiki3/index.php?title=User:AndreaHerman089

Post writing is also a fun, if yyou be acquainted with then you can write if not

it iis complex to write.

Feel free to surf to my web page: free sex videos, Knockoutcuties.Weebly.com,

This is very interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger.

I have joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your fantastic post.

Also, I have shared your site in my social networks!

I was suggested this website by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as

no one else know such detailed about my difficulty.

You’re amazing! Thanks!

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your website in Ie, it looks fine but when opening in Internet

Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up!

Other then that, superb blog!

Hey there! Quick question that’s totally off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly?

My blog looks weird when browsing from my apple iphone.

I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to fix this problem.

If you have any recommendations, please share.

With thanks!

Hello there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it is truly informative.

I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I will appreciate if you continue this

in future. Lots of people will be benefited from your writing.

Cheers!

Hello! I simply would like to give you a big thumbs up for your great info

you’ve got here on this post. I am coming back

to your blog for more soon.

Good article. I will be going through many of these issues as well..

Incredible story there. What occurred after?

Good luck!

What’s up mates, its wonderful post about teachingand completely explained, keep it up all the time.

Magnificent site. Lots of helpful info here. I’m sending it to a

few buddies ans additionally sharing in delicious. And naturally, thank you to your sweat!

Feel free to surf to my blog post lotto

Hey there! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this website?

I’m getting sick and tired of WordPress because I’ve had issues with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform.

I would be great if you could point me in the direction of

a good platform.

I constantly emailed this webpage post page to all my contacts, since if like to read it afterward my links will too.

fantastic points altogether, you simply won a new reader.

What may you suggest about your submit that you made a few days in the past?

Any positive?

I am really inspired with your writing abilities as smartly as with the format to your

blog. Is that this a paid topic or did you customize it your self?

Anyway stay up the nice high quality writing, it is uncommon to look a nice blog like this one these days..

Với mức lương trên 11 triệu mỗi tháng từ công việc toàn thời gian cố định,

Minh cũng nhận ra rằng nếu chỉ

trông chờ vào khoản thu nhập đó thì mua nhà dường như là

không thể hoặc phải chấp nhận sống chung với nợ nần đến già.

Vợ chồng chị Dung cố gắng cắt

giảm các khoản chi tiêu cho những mục đích không thiết yếu

như cafe, du lịch. Nhưng với khoản chi

tiêu tăng dần mỗi tháng, thời gian dự kiến chắn chắn sẽ chậm hơn so với kế hoạch”, chị chia sẻ. Ở hệ đào tạo Trung cấp, nhà trường vẫn luôn chú trọng phát triển các kỹ năng mềm về quản lý, tiêu chuẩn phục vụ và đạo đức nghề nghiệp để tăng sự tự tin cho sinh viên khi làm nghề. Bạn có thể thấy nghề làm bánh, nghề trang điểm và nghề spa thì nghề spa là phù hợp nhất. Chị Dung cũng chia sẻ rằng dù gia đình đã lên kế hoạch chi tiêu cụ thể và cố gắng tuân thủ nhưng với sự thay đổi liên tục của thị trường, việc chi tiêu thực tế hầu như không khớp với mục tiêu đề ra.

Chính vì vị trí quan trọng như trên, tại

vùng đất này trong suốt cuộc chiến tranh, chính quyền Sài gòn dành hơn 1/3

diện tích đất để xây dựng thế bố

phòng trong đó có nhiều đồn, bót, nhà giam Chí Hòa, doanh trại,

kho tàng với trên 30 vị trí quân sự và 07 cuộc cảnh sát, cùng các cư xá

cao cấp như khu cư xá Bắc Hải, cư xá Chí Hòa, Nguyễn Văn Thoại và nhiều khu gia binh cho binh lính và gia đình

phục vụ bộ máy chiến tranh. Vào năm 1959, sân được nâng cấp và

cải tạo để phục vụ các trận bóng đạt chuẩn quốc tế thời điểm đó.

Đặc sản của các con đường ở đây chính là ùn tắc giao thông, nhất là những khung

giờ tan tầm, khung giờ cao điểm, không chỉ vậy, tối đến nơi này cũng không thiếu đi sự náo nhiệt,

sầm uất của dịch vụ mua bán, các quán sá đông

đúc người ra vào. Rạp có tổng cộng 5 phòng chiếu

với chất lượng âm thanh, hình ảnh được đảm bảo

đạt chuẩn để phục vụ nhu cầu xem phim của khách hàng.

At this moment I am going away to do my breakfast, when having my

breakfast coming yet again to read other news.

Do you have any video of that? I’d want to find out more details.

Feel free to visit my web blog – Pagar Beton Precast

This website was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally

I’ve found something which helped me. Thanks a lot!

Cool gay tube:

http://www.zilahy.info/wiki/index.php/User:DJQTheda95467

Hi there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it’s truly informative.

I’m going to watch out for brussels. I will be grateful if you continue this in future.

Many people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Hello, Neat post. There’s a problem with your website in web explorer,

might test this? IE nonetheless is the market leader and a

big section of people will pass over your great writing due to this problem.

I’m not that much of a online reader to be honest but your

sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back later on. Cheers

Hi there to every body, it’s my first go to see of this weblog; this weblog includes remarkable and really fine material in favor of readers.

When some one searches for his necessary thing, therefore he/she wishes to be available that in detail, so

that thing is maintained over here.

I’m curious to find out what blog platform you happen to

be working with? I’m experiencing some minor security problems with my latest website and I would

like to find something more risk-free. Do you have any recommendations?

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d without a doubt donate

to this fantastic blog! I suppose for now i’ll settle for

book-marking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account.

I look forward to new updates and will talk about this blog with my Facebook group.

Talk soon!

It’s an awesome piece of writing designed for all the web viewers; they will take advantage from it I am sure.

Hi my friend! I want to say that this post is amazing, great written and include almost all important infos.

I would like to look extra posts like this .

This post will help the internet visitors for creating new web site

or even a weblog from start to end.

hi!,I like your writing very a lot! share we be in contact more approximately your post

on AOL? I require a specialist in this space to resolve my problem.

Maybe that’s you! Taking a look forward to peer you.

Also visit my blog post พนันออนไลน์

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article

writer for your weblog. You have some really good articles and I think I would be a good asset.

If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d absolutely love to write

some content for your blog in exchange for a

link back to mine. Please shoot me an e-mail if interested.

Regards!

An outstanding share! I have just forwarded this onto a colleague who has been conducting

a little research on this. And he actually bought me dinner simply because I

found it for him… lol. So let me reword this….

Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanx for spending time to

talk about this issue here on your site.

Howdy, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one

and i was just curious if you get a lot of

spam comments? If so how do you protect against it, any plugin or anything you can suggest?

I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any assistance is very

much appreciated.

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here.

The sketch is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish.

nonetheless, you command get bought an nervousness over that

you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come more formerly

again as exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this

increase.

Hello, its nice post about media print, we all

be aware of media is a impressive source of data.

My famuly memhers alll the timee saay that I am wastiing my tijme here at web,

except I know I am getting know-how everyay by reading thes fastidious articlles oor reviews.

Whats up very nice site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your

blog and take the feeds additionally? I am happy to

find so many useful info here within the put up, we’d like work out more techniques on this regard, thank you for sharing.

. . . . .

I am really impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your blog.

Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself?

Either way keep up the excellent quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one nowadays.

Fastidious response in return of this difficulty with genuine arguments and telling all about that.

Hi there, always i used to check weblog posts here

in the early hours in the morning, because i like to gain knowledge of more

and more.

When I originally commented I appear to have clicked on the -Notify

me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on each time

a comment is added I get four emails with the

same comment. There has to be a means you are able to remove me from that service?

Kudos!

There is certainly a lot to learn about this

issue. I love all the points you made.

I was able to find good information from your content.

Hello my family member! I wish to say that this post is amazing, nice written and include almost all significant infos.

I would like to see more posts like this .

I am truly thankful to the holder of this web site who has shared this enormous article at at this place.

Quality articles is the secret to invite the users to pay a quick visit the site, that’s what this web page is providing.

Feel free to visit my homepage: เช่าชุดแต่งงาน

I know this website offers quality depending

posts and additional information, is there any other

web site which presents these kinds of information in quality?

Good article! We will be linking to this particularly great content on our website.

Keep up the good writing.

Also visit my webpage: Casino Online

Great article, totally what I wanted to find.

Nicely put. Appreciate it!

Review my webpage … https://binary-options.homes/?qa=75/purchasing-binary-options

I all the time emailed this website post page to all my associates, for the reason that if like to read it after that my friends will too.

Spot on with this write-up, I honestly believe this

amazing site needs much more attention. I’ll probably be

back again to see more, thanks for the info!

Feel free to visit my web blog – ดูบอลสดวันนี้

I am really loving the theme/design of your web site.

Do you ever run into any browser compatibility issues?

A few of my blog readers have complained about my site not working correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox.

Do you have any advice to help fix this problem?

Hello! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 3gs!

Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts!

Keep up the outstanding work!

You reported this adequately!

my web-site … https://binary-options.homes/?qa=38/characteristics-of-binary-options

Hi there, You have done a fantastic job.

I will certainly digg it and personally suggest to my friends.

I am confident they’ll be benefited from this web site.

My brother recommended I may like this web site. He used to

be totally right. This post actually made my day.

You cann’t imagine just how so much time I had spent for this info!

Thanks!

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer for

your weblog. You have some really great articles and

I think I would be a good asset. If you ever want to

take some of the load off, I’d absolutely love to write some content for your blog

in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an e-mail if interested.

Thank you!

You suggested that effectively!

Here is my web blog https://binary-options.homes/?qa=133/5-rookie-binary-options-errors-you-can-fix-at-present

Whoa plenty of helpful info!

my blog … https://binary-options.homes/?qa=220/what-zombies-can-train-you-about-binary-options

Cool gay movies:

https://example.tanundacricketclub.org.au/pages/LinniexeForehandpk

It’s nearly impossible to find knowledgeable people for this topic, however, you sound

like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

Right here is the perfect website for anybody who would like to understand this topic.

You know a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that I actually

would want to…HaHa). You definitely put a fresh spin on a topic that’s been written about for many years.

Great stuff, just excellent!

I am sure this paragraph has touched all the internet viewers, its really

really pleasant paragraph on building up new web site.

Look into my webpage Casino Online

Cool gay tube:

http://www.freakyexhibits.net/index.php/User:TatianaWynkoop

Link exchange is nothing else however it is only placing the other person’s

website link on your page at appropriate place

and other person will also do same for you.

Greetings from Colorado! I’m bored to death at work so I decided

to browse your site on my iphone during lunch break.

I love the info you present here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home.

I’m amazed at how fast your blog loaded on my mobile ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyhow, very good site!

At this moment I am going to do my breakfast, later than having my breakfast coming again to read

other news.

Hey there! I’ve been reading your web site for a long time now and

finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Lubbock Tx!

Just wanted to tell you keep up the excellent work!

My site :: binary options

Peculiar article, totally what I needed.

Here is my blog post – binary options

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here.

The sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish.

nonetheless, you command get bought an shakiness over that you wish be delivering the following.

unwell unquestionably come further formerly again since exactly

the same nearly very often inside case you shield this

hike.

My web blog :: binary options

Cool gay tube:

http://www.jurisware.com/w/index.php/User:Gregg702169433

I like the helpful information you provide in your articles.

I will bookmark your weblog and check again here frequently.

I am quite sure I will learn lots of new stuff right

here! Good luck for the next!

Hey! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group?

There’s a lot of people that I think would really appreciate

your content. Please let me know. Many thanks

Cheers, Very good information.

Also visit my homepage; https://binary-options.homes/?qa=142/one-tip-to-dramatically-improve-you-r-binary-options

Yoou could certainly see your expertise within the arficle you write.

The world hopes for more passionate writers such as you who aren’t afraid

to mention how they believe. All the time follow

your heart.

Here is my site – 币安期货交易方法

Beneficial information With thanks!

my blog post :: https://binary-options.homes/?qa=79/four-essential-elements-for-binary-options

Tremendous things here. I am very satisfied to see your post.

Thanks so much and I am having a look forward to contact you.

Will you kindly drop me a mail?

Excellent post. I am experiencing many off these issues as

well..

website

Rooxy Palace Casino provides a 24 hour customer assist service hat may bee contacted

any day of the week. DC / Playtech’s premium vary of branded

and unique slots to Canadians for the primary time.

Inside the portal, there’s a piece where we introduce of all one off the best

on-line casinos with bonuses, free spins and all the

advantages offered by these new establishments which

wull take you there byy simply clicking on the model of your liking.

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article.

I’ll be sure to bookmark it and come back to read more

of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I’ll certainly return.

my site https://wakelet.com/wake/ertkiRsErwMBCvsiM4_WK

This site was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found

something which helped me. Cheers!

Review my website … http://www.google.se/url?q=https://katalogfirm-pl.eu/

bookmarked!!, I love your website!

My site; https://afte.org/?URL=https://katalogpolskichfirm.eu/

My brother suggested I would possibly like this blog. He used to be totally right.

This post truly made my day. You cann’t consider just how a lot time I had spent for

this info! Thanks!

Now I am going to do my breakfast, once having my

breakfast coming again to read more news.

Hey very nice webb site!!

Guy .. Excellent .. Wonderful .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take tthe feeds also?

I am satisfied to sesk out a lot of helpful informationn here within the submit, we’d like work

out more techniques iin this regard, thanks ffor sharing.

. . . . .

site

For instance, using oour bonus codes at casinos like Virgin offer

you acchess to a bigger no deposit bonus than the usual supply.

Most of the favored casinos are reliable. Online slot machines are the bsst games to play in the whole gambling trade.

You made some really good points there. I looked on the web to find out

more about the issue and found most people will

go along with your views on this site.

my web-site :: https://stephenyypu057zdrowie2022.weebly.com/blog/chcesz-uzyskac-informacje-o-upadlosci-konsumenckiej-w-szczecinie-nie-ociagaj-sie-znajdz-doswiadczonego-adwokata-w-okolicy-szczecina

Thank you, I’ve recently been looking for information abot this topic for ages andd

yours is the greatest I hazve came upon till now. But, what in regards to the conclusion? Are

you certain concerning the supply?

homepage

With many that aare just like what you’d discover at land-based casinos.

Depositt required. Miin stake £10 on qualifying games. Playing oon the web has always

givesn its possibility to wiin as a lot as you possibly can.

fantastic issues altogether, you just received a brand new reader.

What might you recommend in regards to your submit that you just made some days in the past?

Any sure?

Hi, yes this article is truly good and I have learned lot of things from it on the topic of blogging.

thanks.

I am really grateful to the owner of this web page who has shared this great paragraph at here.

I don’t know whether it’s just me or if perhaps everyone else

encountering issues with your site. It looks like some of the written text

in your posts are running off the screen. Can somebody else

please comment and let me know if this is happening to them too?

This could be a issue with my web browser because I’ve had this

happen before. Appreciate it

Also visit my web-site http://cse.google.com.kh/url?q=https://katalogfirm-pl.eu/

Everything is very open with a clear clarification of the

challenges. It was truly informative. Your website is very useful.

Many thanks for sharing!

certainly like your website but you need to test the spelling on quite a few of your

posts. Several of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very troublesome to inform the reality nevertheless I’ll surely come again again.

Wow, superb blog layout! How long have you been blogging

for? you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your website

is excellent, as well as the content!

What’s Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely helpful and it has helped me out loads.

I’m hoping to give a contribution & assist other users

like its helped me. Great job.

You need to be a part of a contest for one of the finest

websites on the net. I’m going to highly recommend this web site!