Siebe Lijftogt: a critical voice branded a traitor

Former resistance fighter and Indonesian civil servant Siebe Lijftogt (1919-2005) challenged the narrative of a Netherlands that was on the right side of history during the Indonesian independence war on the island of Bali. He held on to the values of the anti-German resistance as they were manifested during the Second World War and encouraged his now powerful resistance friends to take responsibility. Inspired by Sutan Sjahrir, he felt that the Netherlands had only one job: helping to build up a new, independent Indonesia. But in his letters, which his children found after his death, he describes another reality. He became part of the colonial system, a system he fiercely criticized, and it isolated him in a terrible way. In this section Anne-Lot Hoek describes the life story of Siebe Lijftogt, about whom she had previously published as a journalist aiming to give more insight into the role of dissenting voices during the Indonesian independence war.

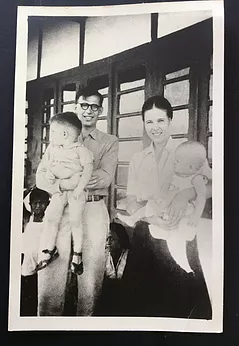

Photos from the archive of the Family Lijftogt show Siebe Lijftogt as a young servant on Bali.

The Swiss-Dutch historian Rémy Limpach describes in his dissertation De Brandende kampong van Generaal Spoor (2016) a forgotten, but meaningful group during the war in Indonesia: the many whistle-blowers. Critical soldiers or civil servants stationed in Indonesia who wrote to editorial boards of Dutch magazines and newspapers and whose letters to their supervisors or parents were published (with or without their permission). Limpach researched who notified the authorities in cases of extreme violence and what kinds of resistance there was against mass violence, but also looked into the consequences of being a whistle-blower and the responses of the authorities in the different cases. There were cases of soldiers sending letters home or to the press, but there were also people who notified judicial or military authorities and people who resisted orders to execute Indonesians without any kind of legal process. Twenty-six soldiers defected to the other side.[efn_note]Remy Limpach, De Brandende Kampongs van Generaal Spoor [The Burning Kampongs of General Spoor] (Amsterdam: Boom Uitgevers, 2016), 623-656.[/efn_note]

The most famous defector is Poncke Princen, who was called a traitor for decades after the incident and was not allowed to enter the Netherlands until 1994. The stories of critical soldiers and civil servants and deserters have received little scholarly attention, which is striking. According to Princen, the cause partly lies in the fact that chauvinism and freedom were such loaded concepts that the previous generation had a very hard time cutting themselves loose from them. In his autobiography Een kwestie van kiezen he underlined the central issue in times of war: “should you, despite conscientious objections, be forced to follow orders, or should you obey to your own conscience?”.[efn_note]Poncke Princen, Een kwestie van kiezen.Zijn levensverhaal opgetekend door Joyce van Fenema (Den Haag: BBNC Uitgevers, 1995), 59.[/efn_note]

Soldiers and civil servants who had been in the Dutch resistance in World War Two were also confronted with questions of conscience. A special example is the story of the civil servant Siebe Lijftogt, who wanted to produce change from within, based on his interpretation of the humanist values of the resistance, and was therefore branded a traitor by his countrymen. It would not be the first time that critics were kaltgestellt (sidelined) on Bali: in 2014, I published in the NRC about a report made by a police agent who had collected almost six hundred pages of information on the role of Dutch authorities in corruption and illegal trade.[efn_note]Anne-Lot Hoek, “Een vuil oorlogje op Bali” [A dirty war on Bali] NRC Handelsblad, November 15, 2014.[/efn_note] One of the critical voices on the island was sidelined by the authorities on the island, and the same happened with the police agent who wrote the report.

Letters on the attic

Lijftogt suffered a similar fate on the island, when he criticized the harsh military course. He was briefly mentioned in The Dark Side of Paradise, the PhD thesis of Canadian historian Geoffrey Robinson, published in 1995. The statement in a footnote that he and his wife were called ‘inlanderliefhebber’[‘native lover’][efn_note]Geoffrey Robinson, The Dark side of Paradise: political violence in Bali (London: Cornell University Press, 1995), 136.[/efn_note] inspired me to trace his relatives.

The encounter with his daughter and son and the discussions we’ve had resulted in my receiving a big suitcase full of letters that he actually wanted to burn before he died, but did not. The letters included Lijftogt’s experiences and ideas as a critical civil servant on Bali and Lombok. They made a huge impact on me personally. I was impressed by Lijftogt’s philosophical thoughts in the midst of a confusing, violent historical crossroads, his modesty, and his honesty, but also by his firmness and, as a former member of the anti-German resistance, his strong emphasis on non-violence towards the Indonesian resistance. But most of all, I admired the fact that he observed and understood things that others didn’t seem to understand or refused to act upon. He was part of the colonial system, but criticized it, and it isolated him in a terrible way. I wrote an article about Lijftogt for the Dutch newspaper NRC[efn_note]Anne-Lot Hoek, “Wij gaan het hier nog heel moeilijk krijgen,” [We are going to have a very difficult time here] NRC Handelsblad, January 9, 2016.[/efn_note] and gave several classes about his life for high schools in Amsterdam and The Hague. For the Amsterdam 4&5 May committee I interviewed Ida Lijftogt at the NIOD (see photo below), as well as Wolter Gerungan, whose father fought as a freedom fighter on Bali.[efn_note] Anne-Lot Hoek “Je huid was of te blank, of te bruin,” [Your skin was either too white or too brown] NRC Handelsblad, August 12, 2016.[/efn_note] The experience of interviewing children of these critics was meaningful for both parties: pieces of information were gathered into a new narrative and placed into a broader historical perspective.

Anne-Lot interviewed Ida, Lijftogt’s daughter and Wolter Gerungan, son of a Menadonese revolutionary on Bali at the Niod on the occasion of a commemoration of Liberation day 5 May 2016.[efn_note]Source: Twitter message NIOD.[/efn_note]

A new, independent Indonesia

Lombok, 4 July 1946

‘The new supervisor […] is a man, raised in the tradition of a proper administrative body and with a proper education. […] He is punctual, precise and deals with people in a nice way. However, everything that is outside of his view is being handled with such ease that it is frightening’. When you hear him speak about the way the English expelled the extremists [the Indonesian resistance] from Bandung […] “These extremists fell from the tree like ripened apples. I can see such a guy lying down there. He got what he wanted – it is what he asked for, right?” This man […] that deals kindly with his servants, loves animals and is also a carpenter, tells his stories with such liveliness and taste that almost make you forget what terrible things he says. He simply does not see it, he does not see the consequences of what happens there, he cannot see it.’[efn_note]The quotations in this biography are taken from the private papers of Siebe Lijftogt and interviews with his daughter Ida Lijftogt; this material is still to be published in forthcoming PhD research.[/efn_note]

This is what Siebe Lijftogt wrote to his wife Linde on the 4th of July of 1946. He was 26 years old at the time, had been part of the Dutch resistance and had left for Indonesia shortly after the Second World War to work as a civil servant. In the year before that, the nationalists led by Sukarno had declared the independence of Indonesia. This was only partly recognized by the Netherlands, triggering a very violent conflict. From 1946 until 1950, Lijftogt held positions on Lombok and Bali. The ethos of the Corps Binnenlands Bestuur (BB) – assisting the local residents – matched very well with his ideals as a former member of the resistance. In his view, the Netherlands had only one job: helping to build up a new, independent Indonesia, ‘with all the best that we brought from home.’ One of the people who inspired Lijftogt was Sutan Sjahrir, whose Indonesische Overpeinzingen he had read with much interest. He urged the home front, the Indology faculty in Utrecht, to read Sjahrir’s work. He offered more than other revolutionaries – ‘he offers a road to healing’, according to Lijftogt.

But in his letters, which the children of Lijftogt found in his attic after he passed away in 2005, he describes another reality. His fellow civil servants, colleagues and supervisors seemed to have the capability to understand the violent battle for independence, but an internalized blind spot prevented them from doing so. That led to even more violence. Lijftogt sees the violence, including that of his own supervisors, as ‘German behavior’. He does not want to be an occupier. That is why he makes a desperate moral appeal to his former resistance buddies, the former board of the National Committee of Resistance: Marie Anne Tellegen, who had become the director of the Cabinet of the Queen, and Lambertus Neher, who had become the delegate of the Supreme Management in Batavia. The latter calls Lijftogt crazy. The recent attention to violence in the Indonesian war for independence (1945-1950) mainly focused on soldiers. The involvement of civil servants with extreme violence has thus far received little attention.

Outspoken

Outspoken

17 January 1969

It is the night on which Dutch Indies veteran Joop Hueting (see video in section Cees Fasseur and his critics) publicly revealed that Dutch soldiers were guilty of war crimes during the battle for independence in Indonesia. His revelations caused a shock throughout the Netherlands. Veterans were filled with rage. Hueting had to go into hiding with his family. The whole commotion led to the so-called Excessennota, a limited investigation into the alleged excessive violence ordered by the government. Siebe Lijftogt, together with his daughter Ida, watched the show in which Hueting made his claims and ‘nodded in agreement’, as she remembers. However, he did not speak about his own experiences in the Dutch Indies nor in the resistance movement.

Lijftogt was the head of the Nationale Comité-courier center in Utrecht and had given the go-ahead for the Februaristaking, which happened in Amsterdam in 1941. He chose civilized resistance over violence. He had wanted to destroy letters and documents from his time in the Dutch Indies, but his daughter stopped him from doing that, she says. ‘He was a humble man who did not speak much. He was afraid that no one would understand him’, says Ida. When she and her brother Gerard recently read his letters, they were shocked. Their father had never been so outspoken and sharp towards them. ‘It is only now that I understand how dramatically significant what my parents experienced there was’, she says.

‘Completely wrong’

Maart/March 1946

Many Dutch military personnel and civil servants were completely exhausted from the hardships in the Japanese camps, Lijftogt observes after he arrived in Batavia, in March 1946. Despite that, the ex-prisoners wanted to return very quickly to the colonial situation they were used to. ‘Linde, you can see the arrogance and the impotence of so many Dutch people here’, he writes to his wife.

According to Lijftogt, his fellow civil servants severely underestimate Indonesian nationalism and believe that the Indonesians are on their side. They do not put much effort into trying to figure out the real situation. ‘They all talk about the hatred of the baboe [maid] for Sukarno and the loyalty of the bicycle repair man’. However, his colleagues have little contact with the baboe and the bicycle repair man, Lijftogt concludes.

In April, Lijftogt addresses his first cry for help to the Nationaal Comité, his supervisors in the resistance and his ‘mentors’. These are the people on whom his moral compass is based, as he would emphasize multiple times. Together with a fellow civil servant he calls for rapid changes in the Dutch Indies policy. ‘We have completely lost power here’ and the Netherlands quickly needs to accept that, ‘if we want to be welcome here in the future.’

On Lombok, his new location where he arrives in April, the political situation is a lot calmer than on Java. Lijftogt becomes responsible for the shelter of political prisoners. He sees this as ‘a unique opportunity to get in touch with the local inhabitants’, as he gleefully writes home. From his letters we see that he becomes more and more understanding of their battle for freedom and even becomes friends with some of them.

His boss, however, Assistant Resident Edy Lapré, who had spent the occupation in a Japanese camp, did not share Lijftogt’s sympathy with the ideals of freedom. When resistance group Bantang Hitam (black bull) spread anti-Dutch pamphlets one night and committed an attack on a military camp, Lapré reacted ‘ as if a bomb had exploded in his mood’. Many people, including some who were innocent, were arrested and forced to sit for long periods in the sun. He also recruited one thousand locals to demonstrate against the resistance movement with slogans that were written by Lapré himself, such as ‘Come on out, the knives and slaughter houses are ready’. Lijftogt confronted his supervisor about this.

That had little effect, as Lapré’s superiors seemed to support his behaviour. The Bali and Lombok Resident, H. Jacobs who was ‘a devilishly fine’ man with lots of humour and tact, even called for executions after the Balinese resistance took revenge on a town that had collaborated with the Dutch. Jacobs gave the chiefs ‘explicit power to straight away kill every pemuda [resistance fighter] that arrived on Lombok, without any kind of legal process. The sooner the better.’

Japanese men who were still free got a price on their head. Lijftogt writes to his family that he feels these measures are ‘completely wrong’. He cannot reconcile these actions with the friendly Resident, who ‘cried during church service’ last Sunday but told Lapré when leaving church to kill anyone who was seen putting up anti-Dutch pamphlets.

‘The pemoeda and the Japanese’ were for many ex-prisoners a case of ‘kill them all’, as Lijftogt writes home. However, when one colleague tells him about the horrible experiences of the Japanese internment camp, Lijftogt becomes more understanding of the behavior of his supervisors, who are ‘on the verge of breaking down’ because of their traumas. ‘People are still very bruised, and so are we’. Then, Lijftogt gets the message that he is being transferred to Bali. The military regime is much harsher there. Jacobs, himself not very gentle, said about this that ‘the daily killing of approximately one hundred men, of which forty per cent are innocent, happens there quite often’, Lijftogt writes to Linde before his departure to Bali.

‘Indigenous-people lovers’

July 1946

On Bali, his conscience quickly gets put to the test even more. ‘How is life here?’, he writes. ‘Linde, we are going to have a very difficult time here.’ His wife is about to board the boat to the Dutch Indies, together with their one-year-old son. ‘The number of human wrecks that one finds here is unsettling’, he says about his ex-prisoner colleagues and the military men.

Despite all this, he is militant. This is the place where he will see if he and his wife can ‘practice their beliefs’. These beliefs were inspired by Christianity, Buddhism and different philosophers. Linde was a nurse with pacifist ideas. ‘She hated all the military stuff’, says Ida. ‘She also went to treat Balinese people with scabies. That was not done, you were not supposed to interfere with these people as a European’. The couple were called ‘indigenous-people lovers’. They became isolated from the European social life, and Lijftogt mediated with the Indonesian resistance. Sometimes, he went away for three weeks to talk to them in their local language. However, he could not prevent the violent killing of the Balinese resistance leader and his followers, on the 20th of November 1946. ‘That really hurt him’, his daughter says, filled with emotion. Lijftogt wrote fiery accounts to Frederik Baron van Asbeck, a friend of the family who was also a professor of international law and a high civil servant in Batavia. He calls the behavior on Bali ‘mild’ compared to South Celebes, but states that on the island 10,000 people have been taken as political prisoners, 2000 of whom have been violently abused. ‘Hitting, kicking, putting them in the sun for hours, hanging them up with their feet barely touching the ground.’

The harsh policy was motivated by the belief that the Balinese people who were loyal to the Dutch could be separated from the ‘extremists.’[efn_note] Robinson, The Dark side, 132.[/efn_note] In reality, that division was difficult to make. The policy only caused the local inhabitants to become victims of violence – by the resistance movement and by the Dutch army with their local supporters. According to Lijftogt, this would lead to a civil war. Similarly, on Java a military solution would end with a ‘more disastrous situation than ever’ and inevitably lead to feelings of revenge among the local inhabitants. He writes this in June 1947 to Van Asbeck – one month later, the Eerste Politionele Actie (First Police Action) would start.

Responsibility

Oktober/October 1947

Van Asbeck is the first one to do something with the information Lijftogt provided him, as his account is published anonymously in the resistance journal Je Maintiendrai, in October 1947. Van Asbeck also sent one of Lijftogt’s letters to former Prime Minister Schermerhorn, who was involved in the negotiations with the Indonesian Republic.

In this letter he writes that he opposes a situation that he feels is inhuman, just as during the German occupation of the Netherlands. He feels like an ‘intellectual SD-member’ who is being used to do ‘dehumanizing work’ like ‘making up ruses to catch pemoeda’s after gaining their trust’. Lijftogt reports in his letter: ‘that we kill, torture and imprison the spes patriae of a people by the hundreds, that we are becoming completely corrupt and hold large drinking parties to forget the mess we made’.

Tellegen sends his letter to Lambertus Neher, who is involved in the negotiations with the Indonesian Republic as a delegate from the Opperbestuur in Batavia. He is not very impressed by the observations of his former resistance pupil. He sees the mood of Lijftogt as ‘bitterness’. Mistakes are being made, but a comparison to the German occupier is a bridge too far for him. Horrible side effects are part of a battle for freedom and are often a response to terror from the Indonesian side, says Neher.

‘Bitterness?’ responds Lijftogt. He wrote his letter because he feels ‘responsible as a Dutchman, for what we, as Dutch, do here’. And if Neher really believes that Dutch terror is a response to Indonesian terror, ‘then you are very poorly informed about what happens outside of Batavia’. It must have been very painful for Lijftogt that the people he used as a moral compass did not understand him. Neher wrote to Tellegen that ‘the mood of the letter feels like mania’. ‘I fear that the young man has been tasked with something too big for him’. And so closed the cover-up.

For the remainder of his life up until his death in 2005, Lijftogt did not want to return to Indonesia. He became a professor of sociology and worked as consultant at the Nederlandse Stichting voor Psychotechniek. During an interview regarding the role of civil servants in Indonesia held in the 1970s, he avoided answering the question about whether the Dutch committed war crimes. ‘He closed it all off and did not want to become a second Joop Hueting’, is what his daughter Ida thinks.

Lijftogt had served in the Dutch resistance ‘because he was unable to do otherwise’. He held on to that moral standard during his time in the Dutch Indies. His progressive ideas caused him to be called a traitor when he left the Dutch Indies. Ida: ‘he was one of the very few people who understood that violence was not a solution. That isolation was a personal drama for him’.