Dissenting Voices

Bibliographic information

This publication is published by Bridging Humanities, an open-access academic publication platform by Brill publishers. In line with the aims of the platform this publication is an experiment in research carried out in co-creation and using digital methodologies.

How to cite?

Maartje Janse & Anne-Lot Hoek. Dissenting Voices: Challenging the Colonial System. (in cooperation with E. Jansz and S. Sijsma), Bridging Humanities. (2019) Vol 1: Issue 2.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/25425099-00102001

Keywords

Colonial history, Dutch East Indies, Anti-colonial protest, Co-creation, Biographies, Historical debate

Summary

This publication emerges from a process of co-creation in which historian Maartje Janse and research journalist Anne-Lot Hoek challenge the dominant national narrative about the colonial experience in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia). In combining journalistic and academic writing with musical performance by musician Ernst Jansz they amplify the critical voices that have spoken out against colonial injustice and that have long been ignored in public and academic debate. Even though it is often suggested that the mindset of people in the past prevented them from seeing what was wrong with things we now find highly problematic, they argue that there was indeed a tradition of colonial criticism in the Netherlands, one that included the voices of many ‘forgotten critics’ whose lives and criticism are the subject of this publication. The voices however were for a long time overlooked by Dutch historians. The publication is organized around the biographies of several critics (whose lives Janse and Hoek have published on before), the historical debate afterwards and includes reflective videos and texts on the process of co-creation.

Maartje Janse started the process by tracing the life history of an outspoken nineteenth-century critic of the colonial system in the Dutch East Indies, Willem Bosch. The authors argue that it was not self-evident how criticism of colonial injustices should be voiced and that Bosch experimented with different methods, including organizing one of the first Dutch pressure groups.

The story of Willem Bosch inspired Ernst Jansz, a Dutch musician with Indo roots, to compose a song (‘De ballade van Sarina en Kromo’). It is an interpretation of an old Malaysian ‘krontjong’ song, that Jansz transformed into a protest song that reminds its listeners of protest songs of the 1960s and 1970s. Jansz, in his lyrics, adds an indigenous perspective to this project. He performed the song during the Voice4Thought festival in 2016, a gathering that aimed to reflect upon migration and mobility in current times. Filmmaker Sjoerd Sijsma made a video ‘pamplet’ in which the performance of Ernst Jansz, an interview with Maartje Janse, and historical images from the colonial period have been combined.

Anne-Lot Hoek connected Willem Bosch to a series of twentieth-century anti-colonial critics such as Dutch Indies civil servant Siebe Lijftogt, Indonesian nationalists Sutan Sjahrir, Rachmad Koesoemobroto, Dutch writer Rudy Kousbroek and Indonesian activist Jeffry Pondaag. She argues that dissenting voices have been underrepresented in the post-war debates on colonialism and its legacy for decades, and that one of the main reasons is that the notion of the objective historian was not effectively problematized for a long time.

Links

Bridging Humanities, overview publications.

Brill Puplishers, overview publications.

References

This publication is published by Bridging Humanities, an open access academic publication platform by Brill publishers. In line with the aims of the platform this publication is an experiment of research carried out in co-creation and using digital methodologies.

Introduction: A tradition of anti-colonial dissenting voices?

- Gloria Wekker, White Innocence. Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. (London: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Piet Emmer, Het zwart-witdenken voorbij. Een bijdrage aan de discussie over kolonialisme, slavernij en migratie [Beyond black-and-white thinking. A contribution to the discussion about colonialism, slavery and migration] (Amsterdam: Nieuw Amsterdam, 2017). Marco Visscher, “Historicus Piet Emmer: ‘Zij die over ons slavernijverleden het hoogste woord voeren, weten sterk te overdrijven’,” [Historian Piet Emmer: “Those who have the highest word over our slavery past know how to exaggerate strongly”] De Volkskrant, January 6, 2018.

- Kester Freriks, “Tempo doeloe – ook een mooie tijd,” [Tempo doeloe – also a good time] NRC Handelsblad, October 5, 2018.

- Zihni Özdil, “De drogredeneringen van Piet Emmer,” [The fallacies of Piet Emmer] Historiek, August 3, 2014.

- Marco Visscher, “Piet Emmer: ‘zij die over ons slavernijverleden het hoogste woord voeren weten sterk te overdrijven’,” [Piet Emmer: “those who have the highest word over our slavery history know how to exaggerate strongly] De Volkskrant, January 6, 2018; Piet Emmer, “De slavernij van het Mauritshuis,”[The slavery of the Mauritshuis] Historiek, July 31, 2014. A reply by Emmer on the historical platform Historiek to the blogpost: Zihni Özdil, “Slavernij-achtergrond Mauritshuis is zorgvuldig gewist. De gepasteuriseerde geschiedenis van het Mauritshuis,” [Slavery background of the Mauritshuis has been carefully erased. The pasteurized history of the Mauritshuis] Historiek, July 2, 2014. Willem de Haan, “Knowing What We Know Now: International Crimes in Historical Perspective,” Journal of International Criminal Justice, 13, no.4 (2015): 783-799, https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqv032 [restricted access]; Remco Meijer, Oostindisch doof. het Nederlandse debat over de dekolonisatie van Indonesië [Oostindisch deaf. the Dutch debate about the decolonization of Indonesia] (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 1995).

- Marrigje Paijmans, “Ook in de zeventiende eeuw werd het debat over kolonialisme gesmoord,” [Also in the seventeenth century the debate about colonialism was smothered] Over de muur, May 4, 2018.

- De Haan, “Knowing,” 3-6.

- For more information see the English overview of literature in the Beb Vuyk entry on Wikipedia and a biography in Dutch by Kees Kuiken, Vuijk, Elizabeth, Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland, October 11, 2017.

- Henk van Randwijk, ‘Omdat ik Nederlander ben,’ [Because I am a Dutch citizen], Vrij Nederland, July 26,1947. Republished in in 1999 by the NRC Handelsblad.

- See also The Djaya brothers. Revolusi in The Stedelijk. Exhibition 9 June – 2 September 2018. Website Stedelijk Museum.

- Until Maartje Janse started to publish about him. See Maartje Janse, “‘Waarheid voor Nederland, regtvaardigheid voor Java’. De geschiedenis van de Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan,” [‘Truth for the Netherlands, lawfulness for Java’. The history of the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese] Utrechts Historische Cahiers 20 (1999) nr. 3-4.

- For more (post)colonial life writing see Rosemarijn Hoefte, Peter Meel and Hans Renders, Tropenlevens: de (post)koloniale biografie [Tropical lives: the (post) colonial biography](Leiden/Amsterdam: KITLV/Boom, 2008).

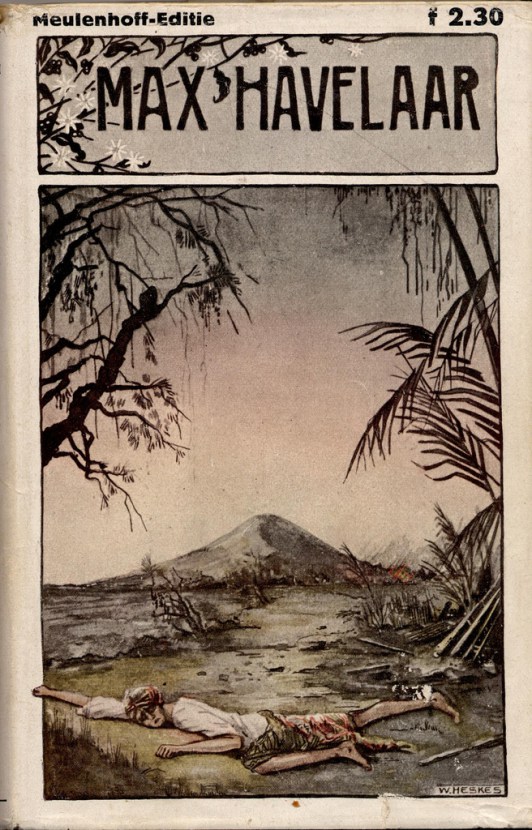

- Multatuli (pseudonym of Eduard Douwes Dekker), Max Havelaar of de koffij-veilingen der Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappy [Max Havelaar or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company] (Amsterdam, J. de Ruyter, 1860).

- See for instance Nop Maes, Multatuli voor iedereen (maar niemand voor Multatuli) [Multatuli for everyone (but nobody for Multatuli)] (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2000).

- See for instance all essays in Theo D’haen and Gerard Termorshuizen (eds), De geest van Multatuli. Proteststemmen in vroegere Europese koloniën [The spirit of Multatuli. Protest voices in former European colonies] (Leiden: 1998); Remieg Aerts, Theodor Duquesnoy, and Jan Breman (eds), Een ereschuld. Essays uit De Gids over ons koloniaal verleden [A debt of honor. Essays from De Gidsabout our colonial past] (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1993).

- Such as W.R. van Hoëvell, Slaven en vrijen onder de Nederlandsche wet [Slaves and free persons under the Dutch law] (Zaltbommel: Joh. Noman en Zoon, 1854). Second print (1855) available at the website of De Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren (DBNL).

- For instance the poem De Vloekzang van Sentot of De laatste dag der Hollanders op Java [The Curse Song of Sentot or The Last Day of the Dutch on Java]. In: Multatuli, Max Havelaar, (1875).

- Janny de Jong, Van batig slot naar ereschuld. De discussie over de financiele verhouding tussen Nederland en Indie en de hervorming van de Nederlandse koloniale politiek 1860-1900 [From merciful lock to honorary debt. The discussion about the financial relationship between the Netherlands and the East Indies and the reform of the Dutch colonial policy 1860-1900] (’s Gravenhage: SDU 1989); also see Ewald Vanvugt, Nestbevuilers. 400 jaar Nederlandse critici van het koloniale bewind in de Oost en de West [Nest polluters. 400 years of Dutch critics of the colonial rule in the East and the West] (Amsterdam: Babylon-De Geus 1996).

- Maartje Janse, “Representing Distant Victims: The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880,” BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review 128-1 (2013): 53-80; Harry A. Poeze, In het land van de overheerser: Indonesiërs in Nederland 1600-1950 [In the land of the ruler: Indonesians in the Netherlands 1600-1950] (Dordrecht: Foris Publications, 1986).

- F. Tichelman, “De sociaal-democratie en het koloniale vraagstuk (De SDAP en Indonesië 1894-1914),” [Social democracy and the colonial issue (SDAP and Indonesia 1894-1914)] in: M. Campfens e.a. (eds), Op een beteren weg. Schetsen uit de geschiedenis van de arbeidersbeweging aangeboden aan mevrouw dr. J.M. Welcke [On a better road. Sketches from the history of the labor movement presented to Mrs. Dr. J.M. Welcke] (Amsterdam, 1985), 158-171; F. Tichelman, “Socialist Internationalism and the Colonial World,” in: Frits van Holthoon and Marcel van der Linden, Internationalism in the Labour Movement, 1830-1940 (Leiden: Brill, 1988), 87-108; Erik Hansen, ‘Marxists and Imperialism: The Indonesian Policy of the Dutch Social Democratic Workers Party, 1894-1914’, Indonesia 16 (1973): 81-104; J.A.A. van Doorn “De sociaal- democratie en het koloniale vraagstuk,” [Social democracy and the colonial issue] Socialisme en Democratie 11 (1999): 483-492.

- Soorjo Poetro, “Een Indiers uitspraak,” [An Indo verdict] Het Volk: dagblad voor de arbeiderspartij, July 2, 1918. For the Indische Vereeniging also see Klaas Stutje, “Indonesian identities abroad International Engagement of Colonial Students in the Netherlands, 1908-1931,” BMGN, Volume 128-1 (2013): 153.

- A portrait of Anton de Kom is included in the series Echte Helden by Herman Morssink, see section Siebe Lijftogt.

- Martijn Blekendaal, “Anton de Kom (1898-1945) en Mohammad Hatta (1902-1980),” Historisch Nieuwsblad 5 (2010).

- Paul Bijl, Emerging Memory: Photographs of Colonial Atrocity in Dutch Cultural Remembrance (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016).

- Abraham De Swaan, “Postkoloniale absences,” [Postcolonial absences] De Groene Amsterdammer, May 10, 2017.

- Jan Breman, Koelies, planters en koloniale politiek [Coolies, planters and colonial politics] (Floris, 1987) Jan Breman, Taming the Coolie Beast: Plantation Society and the Colonial Order in Southeast Asia (Dehli: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- Boven-Digoel is discussed in the section Sutan Sjahrir.

- Willem Oltmans, Mijn vriend sukarno [My friend Sukarno] (Utrecht: Het Spectrum, 1995).

- The interview with Hueting and the excessennota are discussed in the section Fasseur and his critics.

- J.A.A. van Doorn and W.J. Hendrix, Ontsporing van geweld: over het Nederland/Indisch/Indonesisch conflict [Derailments of violence: about the Netherlands/Indo/Indonesian conflict] (Rotterdam: Universitaire pers, 1970).

- Lou de Jong, Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 1939-1945 deel 11A [Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Second World War 1939-1945 part 11A] (Amsterdam: Rijksinstituut voor oorlogsdocumentatie, 1984).

- Stef Scagliola, Last van de Oorlog, de Nederlandse oorlogsmisdaden in Indonesië en hun verwerking [Burden of the War, Dutch war crimes in Indonesia and their processing] (Rotterdam: Balans, 2002), 92.

- OVT Radio, “Vergeten Antikoloniale stemmen,” [Forgotten Anticolonial voices], VPRO, July 1 , 2018. Original published at OVT radio NPO1. Published with English subtitles for this publication at the Youtube channel of Voice4Thought.

A process of co-creation

- ‘The Voice4Thought Foundation and the Bridging Humanities platform developed from the research project Connecting in Times of Duress: Understanding communication and conflict in Middle Africa’s mobile margins’ (2012-2017). The project experimented with new media and alternative forms of academic publications.

- See for example the ‘Pamphlet of Croquemort‘. The video is part of the Bridging Humanities publication Mirjam de Bruijn, Croquemort: a biographical journey in the context of Chad. Bridging Humanities, 1 (2017). DOI: 10.1163/25425099-00101001.

- Maartje Janse, De Afschaffers. Publieke opinie, organisatie en politiek in Nederland 1840-1880 [The Abolitionists. Public opinion, organization and politics in the Netherlands 1840-1880] (Amsterdam: Wereldbibliotheek, 2007).

- The original publication about Willem Bosch on the Voice4Thougth website was published in Dutch.

- For an overview of the works of Ernst Jansz, see his website.

- The articles of Anne-Lot can be found on her website.

Research journalism and the need for dissenting sources

- NOS Buitenland (2016), “Historicus Anne-Lot Hoek,” Nieuwsuur, December 2, 2016 [Video in Dutch].

- Rudi Boon, “De martelkamer heette het Karl Marx ontvangstcentrum,” [The torture chamber was called the Karl Marx reception center] De Groene Amsterdammer, September 3, 1989.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, Aan de goede zijde van de strijd: mensenrechtenschendingen van bevrijdingsbeweging Swapo en de reactie daarop van de Nederlandse solidariteitsbeweging [On the good side of the fight: human rights violations of the Swapo liberation movement and the response of the Dutch solidarity movement] (Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2005).

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Anti-apartheidsactivisten die het ANC jarenlang door dik en dun steunden, kijken terug. Hebben ze de beweging te veel geromantiseerd?,” [Anti-apartheid activists who supported the ANC for years through thick and thin look back. Have they romanticized the movement too much?] Vrij Nederland (Special Nelson Mandela 1918-2013), December 6, 2013.

- Brinkman and Anne-Lot Hoek, “Bricks, Mortar and Capacity Building: A Socio-Cultural History of SNV Netherlands Development Organisation,” Afrika-Studiecentrum Series, vol. 18 (2010).

- NOS, “Het bijna vergeten bloedbad van Rawagede,” [The almost forgotten massacre of Rawagede] NOS Binnenland, September 14, 2011 [Video in Dutch, English subtitles added].

- The full recording of the interview can be found here.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Ook op Sumatra richtten de Nederlanders een bloedbad aan,” [The Dutch also committed a massacre on Sumatra] NRC Handelsblad, February 13, 2016.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Rengat, 1949 (Part 1),” Inside Indonesia, September 12, 2016.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Bloedbaden op Bali,” [Massacres in Bali] Vrij Nederland, November, 13, 2013.

- Personal profile on the website ID writers.

- Personal profile on the website ID writers.

- Personal profile on the website NIOD.

- Overview of published works on Academia.

- Link to the project website Independence, decolonisation, violence and war in Indonesia 1945-1950.

- NPO1, “Het bloedbad van Rengat,” [The massacre of Rengat], radio reportage by Anne-Lot Hoek and Sander Bartling, February 14, 2016, origninal at website of NPO1.

Willem Bosch 'champion of the Javanese'

- For more on the relation between Willem Bosch and Multatuli, see Maartje Janse, “‘Om eene hervorming tot stand te brengen, behoort men te weten, wat men wil’. Multatuli en de Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan (1866-1877),” [To bring about a reform, one must know what one wants. Multatuli and the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese] in Multatuli Jaarboek (Hilversum: Verloren, 2016), 35-50.

- Most importantly: Maartje Janse, De afschaffers, publieke opinie, organisatie en politiek in Nederland 1840-1880 [The abolitionists, public opinion, organization and politics in the Netherlands 1840-1880] (Amsterdam: Wereldbibliotheek, 2007); Maartje Janse, “De balanceerkunst van het afschaffen. Maatschappijhervorming beschouwd vanuit de ambities en de respectabiliteit van de negentiende-eeuwse afschaffer,” [The balancing art of abolition. Societal reform viewed from the ambitions and respectability of the nineteenth-century abolitionist] De Negentiende Eeuw 29, 1 (2005): 28-44. These publications show that prior to the founding of the first political parties in the Netherlands, some citizens organized themselves into associations to promote the abolition of all kinds of social abuses. These single issue movements were concerned with the abolition of slavery, alcohol abuse, taxes on newspapers, the Education Act of 1857, and in the case of Willem Bosch and his Society for the Benefit of the Javanese, with the cultural system in the Dutch East Indies. The first “abolitionists” claimed to be apolitical and to be protesting against what was wrong in society based on their beliefs, feelings and conscience. But gradually their protests became politicized, ultimately changing the nature of politics. It was partly due to the abolitionists that towards the end of the nineteenth century politics increasingly involved questions of morality and religion, and that more and more people thus more strongly identified with politics, and became more involved in politics.

- See for example: Maartje Janse, “Nederlands protest tegen de slavernij,” [Dutch protest against slavery] Slavernij en Jij. or Maartje Janse, “Meer protest tegen slavernij dan gedacht,” [More protest against slavery than has been thought] Kennislink, October 17, 2011; or Maartje Janse “Holland as a Little England’? British Anti-Slavery Missionaries and Continental Abolitionist Movements in the Mid Nineteenth Century,” Past & Present, Volume 229, Issue 1 (November 2015): 123–160, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtv037 [restricted access].

- copies of original Willem Bosch memoirs p. 1-21; Willem Bosch memoirs p. 22-42.

- A.H. Borgers, Doctor Willem Bosch en zijn invloed op de geneeskunde in Nederlandsch Oost-Indië [Doctor Willem Bosch and his influence on medicine in the Dutch East Indies] (Utrecht, 1941).

- For more on Bosch’ career in the Military Medical Service see Borgers, Doctor Willem Bosch.

- For more on the changing political culture see: Maartje Janse, “Representing Distant Victims: The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880,” BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review, 128-1 (2013): 53-80, http://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.8355 [open access].

- Arnhemsche Courant, May 21, 1874. Link

- ‘In Memoriam’, Nederland en Java, June 1, 1874.

- For some of Bosch’s publications see: Willem Bosch, ‘Ik wil barmhartigheid en niet offerande.’ Eene wekstem aan Nederland tot barmhartigheid, rechtvaardigheid en pligtsbetrachting jegens de Javanen [‘I want mercy and not sacrifice.’A wake-up call to the Netherlands for mercy, justice and duty to the Javanese] (Arnhem: Breijer, 1866). For a full list of Bosch’s publications see Bosch’s Bibliography.

- For more information on the debates about pressure groups see: Maartje Janse, “A Dangerous Type of Politics? Politics and Religion in Early Mass Organizations: The Anglo-American World, c. 1830,” in Joost Augusteijn, Patrick Dassen, and Maartje Janse (eds), Political Religion Beyond Totalitarianism: The Sacralization of Politics in the Age of Democracy (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 55–76; and Maartje Janse, “‘Association Is a Mighty Engine’. Mass Organization and the Machine Metaphor, 1825 1840,” in Maartje Janse and Henk te Velde (eds), Organizing Democracy: Reflections on the Rise of Political Organizations in the 19th Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 19-42.

- On the importance of the Anti-corn law league see Maartje Janse’s article in European Review of History here.

- See also: Association Life in the Netherlands (from 1780) and Representing Distant Victims The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880.

- Bosch, ‘Ik wil barmhartigheid en niet offerande’.

- Willem Bosch, Tweede wekstem aan Nederland tot barmhartigheid, rechtvaardigheid en pligtsbetrachting jegens de Javanen [Second wake-up call to the Netherlands for mercy, justice and duty to the Javanese] (Arnhem: Breijer, 1866).

- For more on the relationship between the Maatschappij and politics see: Maartje Janse, “Chapter 4,” in De Afschaffers.

- For examples see Janse, “‘Om eene hervorming tot stand te brengen, behoort men te weten, wat men wil’. Multatuli en de Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan (1866-1877),” [To bring about a reform, one must know what one wants. Multatuli and the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese] in Multatuli Jaarboek (Hilversum: Verloren, 2016), 47.

The Ballad of Sarina & Kromo

- The song was published on the the cd (and the eponymous autobiographical novel) De Neerkant by Ernst Jansz (2017).

- A translation of the song Tomorrow’s A Long Time by Bob Dylan.

The Pamphlet

- For the pamphlet historical footage found on YouTube has been used. This list shows the orginal films and links to the videos on YouTube.

Nederlands Filmarchief, “Oude filmbeelden van Nederlandsch-Indië, 1910-1915,” [Old film images from the Dutch East Indies, 1910-1915] Tempo doeloe I. Films directed by J.C Lamster and produced by Het Nederlands Koloniaal Instituut Amsterdam: Tocht per auto door Weltevreden (1923), De opening van de landbouwhogeschool te Kopo, Autotocht door Bandoeng (1913), De strafgevangenis van Batavia, Het Leven de Europeanen in Indie, Het leven van de Inlander in de Dessa. Sfeerbeelden van een lang vervlogen tijd [Tour by car through Weltevreden (1923), The opening of the agricultural college in Kopo, Car tour by Bandoeng (1913), The penal prison in Batavia, The life of Europeans in India, The life of the Inlander in the Dessa. Atmospheric images from a bygone era]. For more information about J.C. Lamster see the website of Eye Amsterdam. For the video on YouTube see: “Nederlands Indie 1910-1915,” published on August 6, 2014.

Nederlands Filmarchief, “Oude filmbeelden van Nederlandsch-Indië, 1915-1925,” [Old film images from the Dutch East Indies, 1910-1915] Tempo doeloe II. Films produced by Het Nederlands Koloniaal Instituut Amsterdam: Nina het dienstmeisje gaat inkoopen doen. Schets uit het Indische leven (?); Bezoek aan een theeplantage (1914); De rijstbouw op droge velden bij de Karo-Bataks; Aankomst van de S.S. “Rumphius”; Het immigranten asyl. Voor gebrekkige koelies die niet naar hun land willen terugkeeren; Borneo (1919); Jaarbeurs en pasar Malam, directed by J. John (1923). [Nina the maid goes shopping. Sketch from Indian life (?); Visit to a tea plantation (1914); Rice cultivation on dry fields near the Karo-Bataks; Arrival of the S.S. “Rumphius”; The immigrant asyl. For defective coolies who do not want to return to their country; Borneo (1919); Jaarbeurs and pasar Malam, directed by J. John (1923)] . For the video on YouTube see: “Baboe Mina, Tanah Batak, Balewan dan Bornoe,” published on May 5, 2013.

Nederlands Filmarchief, “Insulinde zooals het leeft en werkt 1927-1940,” [Insulinde as it lives and works 1927-1940] Tempo doeloe III & IV. Compilation from the movies Over mooie zeeën naar de tropen, Mooi Bandoeng, Heerlijke reizen in het Tenggerland, Excursie naar Indië’s machtige elementen, Langs Java’s mooie wegen, Bali, Lijkverbranding op Bali [Across beautiful seas to the tropics, Beautiful Bandoeng, Wonderful journeys in the Tenggerland, Excursion to India’s powerful elements, Along Java’s beautiful roads, Bali, Burial burning in Bali]. For the video on YouTube see: “Batavia, Bandung, Surakarta, Jogjakarta, Surabaya, Madura (1927 – 1940),” published on May 6, 2013.

It is interesting to note that Rudy Kousbrouk (see section Cees Fasseur and his critics) critically analyzed the Tempo Doeloe films. Rudy Kousbroek, “Warme roerloosheid; Tempo Doeloe op video,” [Warm motionlessness; Tempo Doeloe on video] NRC Handelsblad, June 13, 1997. While the images recall warm memories to the land he was born, he states: “Not all film images are pleasant to see. The “atmospheric images of Bandjermassin, the capital of Borneo, from which elephants, monkeys and tigers are exported to America” are sometimes unbearable to me. What also strikes in some old archive films is the self-evident Eurocentric sense of superiority: the Indonesians as interesting people of nature – something that now has such an enormous taboo on it that in itself is gripping to see – and almost never as ordinary people with ordinary daily lives like ourselves. For example, there are important aspects of Dutch-Indian society that are completely ignored. It is striking, for example, that it seems that there were no Indos at the time: there were Europeans and Natives, and there was nothing in between. There is probably almost no film material about it: it would be worthwhile to gather everything that can be found in that area and to use it for a film dedicated to this subject.”

NIOD, “Nederlands – Indië tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog Trailer” [Dutch East Indies during the Second World War] April 5, 2012. Distributor Kolmio Media, Label Universal Music. For the video on YouTube see: “Nederlands Indië tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog Trailer,” published on May 7, 2012.

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. Inc Akron. O., “The Island of Yesterday Sumatra Dutch east Indies”, Motion Picture Division. For the video on YouTube see: “Sumatra Island of Yesterday 1920 Goodyear Rubber Plantations in the Dutch East Indies,” published on February 3, 2017. The video is also archived at Internet Archive, as part of the Prelinger Archives.

Eugene W. Castle, “The World Parade, Bali Paradise”. Castle Films, MCMXLVI. For the video on YouTube see: “Silent 8mm movie – The World Parade – Bali, Paradise Isle (ca.1930),” published on November 30, 2014.

Herman Drost, “Indonesië ± 1930-1938 Sumatra”. Post-processing Wim Heins. 2012. For the video on YouTube see: “Indonesia (Sumatra) dagelijks leven 1930-1938,” published on July 20, 2012.

Willy Mullens, “Batavia. Part 1. (1929).” Haghe Film, with support of the Ministry of Colonies and Education. For the video on YouTube see: “Batavia Jakarta 1929 old days Indonesia,” published on August 31, 2009.

William M. Pizor, “Virgins of Bali. Land of love and romance”. Principal distributing corp. Produced and narrated by Deane H. Dickason. For the video on YouTube see: “Virgin of Bali2.flv.mp4,” published on December 6, 2011 and “The Virgin Of Bali 1926 Doc,” published on February 6, 2016.

YouTube: “Bali 1910″ [information about original film missing]

YouTube: “Bali old video 12: circa 1935 The Island of Bali ” [information about original film missing]

Online archives with historical films of Indonesia:

Film Database Eye Film museum Nederlands-Indië

Collection ‘De kolonie Nederlands-Indië’ Instituut Beeld en Geluid

- Multatuli (pseudonym of Eduard Douwes Dekker), Max Havelaar of de koffieveilingen der Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappy [Max Havelaar or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company] (Amsterdam: J. de Ruyter, 1860), 233-254 (Chapter 17).

Sutan Sjahrir: Indonesian revolutionary

- C. Smit, Het dagboek van Schermerhorn [Schermerhorn’s diary] (Utrecht: Nederlands Historisch Genootschap, 1970).

- Klaas Stutje, “Indonesian identities abroad International Engagement of Colonial Students in the Netherlands, 1908-1931,” BMGN, volume 128-1 (2013): 153. This text is based on previous journalistic work, in particular the article: Anne-Lot Hoek, “In naam van merkeda,” [in the name of Merkeda] De Groene Amsterdammer, August 2, 2017.

- ‘Een Indiers uitspraak,’ Het Volk: dagblad voor de arbeiderspartij, July 2, 1918.

- Sutan Sjahrir, Indonesische Overpeinzingen [published in English as Out of Exile] (Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 1945).

- Paul Bijl, “Human Rights and Anticolonial Nationalism in Sjahrir’s Indonesian Contemplations,” Law & Literature, 29:2 (2017): 252.

- Ibid: 95.

- Kees Snoek, “Soetan Sjahrir. De strijder,” [Soetan Shahrir. The warrior] in Rosemarijn Hoefte, Peter Meel & Hans Renders (ed.), Tropenlevens. De (post)koloniale biografie [Tropical lives. The (post) colonial biography] (Leiden/Amsterdam: Boom, 2008), 170-171.

- Journalist Karin Amatmoekrim wrote an article about Boven-Digoel for the online platform De Correspondent in a series about ‘silenced histories’ in which she compared it to Guantánomo because it was a place of exile where political prisoners were banned without trial. Karin Amatmoekrim, “Hoe Nederland zijn strafkamp in Nieuw-Guinea trachtte te vermommen.” [How the Netherlands tried to disguise its prison camp in New Guinea] De Correspondent, March 7, 2018.

- Sjahrir, Indonesische Overpeinzingen, 58, 60.

- Spaarnestad Photo, collection Het Leven (unknown photographer), ‘Communistische gevangenen. Geboeid worden een aantal communistische “raddraaiers” van boord gezet en geïnterneerd op Boven-Digoel. Indonesië, 1927’ [Communist prisoners. A number of Communist “wheel-turners” are handcuffed and boarded at Boven-Digoel. Indonesia, 1927]. See: Geheugen van Nederland.

- Sjahrir, Indonesische Overpeinzingen, 88-93.

- Ibid, 89.

- See for instance: Inge Brinkman in cooperation with Anne-Lot Hoek, Bricks, mortar and capacity building, A Socio-Cultural History of SNV Netherlands Development Organisation (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

- Sutan Sjahrir, Onze Strijd [Our Struggle] (Amsterdam: Vrij Nederland, 1945).

- Radio broadcast from 1945, inserted in the article Australian waterfront workers support Indonesian independence against the Dutch.Website ABC news Australia.

- Speech Upik Sjahrir on Exhibition ‘The Linggadjati conference’ in The Hague, February 15 2010. Website of the Indonesia Nederland Society.

- Rudolf Mrázek, Politics and Exile in Indonesia (New York, Cornell Southeast Asia Program, 1994), 494.

- Ibid, 497.

- Ibid, 464.

- Upik Sjahrir, 2010.

- Joty ter Kulve – van Os visited the parental home in 2012, a journey captured in the form of a documentary made by Twan Spierts ‘Terug naar Linggajati’ [Back to Linggajati], which was screened by Omroep West on 14 October 2012.

Siebe Lijftogt: a critical voice branded a traitor

- Remy Limpach, De Brandende Kampongs van Generaal Spoor [The Burning Kampongs of General Spoor] (Amsterdam: Boom Uitgevers, 2016), 623-656.

- Poncke Princen, Een kwestie van kiezen.Zijn levensverhaal opgetekend door Joyce van Fenema (Den Haag: BBNC Uitgevers, 1995), 59.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Een vuil oorlogje op Bali” [A dirty war on Bali] NRC Handelsblad, November 15, 2014.

- Geoffrey Robinson, The Dark side of Paradise: political violence in Bali (London: Cornell University Press, 1995), 136.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Wij gaan het hier nog heel moeilijk krijgen,” [We are going to have a very difficult time here] NRC Handelsblad, January 9, 2016.

- Anne-Lot Hoek “Je huid was of te blank, of te bruin,” [Your skin was either too white or too brown] NRC Handelsblad, August 12, 2016.

- Source: Twitter message NIOD.

- The quotations in this biography are taken from the private papers of Siebe Lijftogt and interviews with his daughter Ida Lijftogt; this material is still to be published in forthcoming PhD research.

- Robinson, The Dark side, 132.

Rachmad Koesoemobroto

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “In naam van Merkeda,” [In the name of Merkeda] De Groene Amsterdammer, August 2, 2017. From interview with Murjani Kusumobroto and Iwan Faiman, Amsterdam, June 7, 2017.

- See two blog posts on the website of the Indonesian writer Joss Wibisono [in Indonesian]. One on the life history of Irawan Soejono, and one on the remembrance of Irawan Soejono in Leiden, with a photo of Ernst Jansz who spoke at the meeting.

- Ernst Jansz, De Overkant [The other side] (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer, 1985) 59.

- Gerard Mulder and Paul Koedijk, H.M. van Randwijk: een biografie [H.M. van Randwijk: a biography] (Amsterdam: Raamgracht, 1988) 338.

- Henk van Randwijk, “Omdat ik Nederlander ben,” [Because I am a Dutchman] Vrij Nederland, July 26, 1947. Later because of its significance, also published by the NRC Handelsblad and De Groene Amsterdammer.

- Interview Kusumobroto and Faiman.

- See also his website.

- “Indonesiers keeren naar hun vaderland terug”[Indonesians return to their home country], Het Parool, December 9, 1946.

- Interview Kusumobroto and Faiman.

- Ibid.

- Ibid and see: Ton Hydra, “Gevangenen en vrije mensen,” [Prisoners and free people] Nieuwe Leidse Courant, April 20, 1978.

- See the website of the organization In mijn buurt [in Dutch].

- The website [in Dutch] also presents the meeting in 2017 at the Tropenmuseum at which Anne-Lot spoke with Joty Ter Kulve about Sutan Sjahrir and Ernst Jansz spoke about his father. The Tropenmuseum functioned as the headquarters of the Indonesian resistance against the Germans during the Second World War.

Cees Fasseur and his critics

- OVT Radio, “Geschiedenisgasten: Remco Raben en Rudy Kousbroek,” [History guests: Remco Raben and Rudy Kousbroek] VPRO, July, 14, 2002. Original at website of the VPRO.

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “The danger of a single story,” filmed July 2009 at TEDGlobal 2009, Oxford.

- See also: Freek Colombijn & J. Thomas Lindblad (eds), Roots of Violence in Indonesia (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2006).

- Rémy Limpach, De brandende kampongs van Generaal Spoor [The burning kampongs of General Spoor] (Amsterdam: Boom, 2016).

- Historian J.C. van Leur, writer Tjalie Robinson and the non-Western sociologist Wim Wertheim had been equally strong anti-colonial voices.

- Rudy Kousbroek, “De diachronie van de doofpot,” [The diachrony of the cover-up] NRC-Handelsblad, April 29, 1994.

- Cees Fasseur, interview in: Remco Meijer, Oostindisch Doof: het Nederlandse debat over de dekolonisatie van Indonesië [Being deaf the Eastern-Indies way: the Dutch debate about the decolonization of Indonesia] (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 1995); Interview with Cees Fasseur, 105.

- Kousbroek, “De diachronie”.

- Jan Breman, Koelies, planters en koloniale politiek [Coolies, planters and colonial politics] (Dordrecht: Foris, 1987).

- Rudy Kousbroek, Het Oostindisch Kampsyndroom [The East Indies camp syndrome] (Amsterdam: Olympus, 1992), 163.

- Stef Scagliola, Last van de oorlog. De Nederlandse oorlogsmisdaden in Indonesië en hun verwerking [Burden of the war. The Dutch war crimes in Indonesia and their processing] (Amsterdam: Balans, 2002).

- See for example: “Zinloos en misselijk,” [Meaningless and nauseous],’ De Telegraaf, January 21, 1969.

- De Excessennota, nota betreffende het archiefonderzoek naar de gegevens omtrent excessen in Indonesië begaan door Nederlandse militairen in de periode 1945-1950 Ingeleid door Jan Bank [The Excessennota, memorandum concerning the archival research into the data on excesses committed in Indonesia by Dutch soldiers in the period 1945-1950 Introduced by Jan Bank] (first edition 1969, second edition 1995).

- E. Locher-Scholten, “S.I. Scagliola, Last van de oorlog. De Nederlandse oorlogsmisdaden in Indonesië en hun verwerking,” BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review, 119.1 (2004): 146.

- Cees Fasseur, Dubbelspoor: herinneringen [Double track: memories] (Amsterdam: Balans, 2016), 143.

- Ibid, 144.

- Excessennota, 83.

- Limpach, De brandende kampongs, 334.

- Jouri Boom, Nieuw bewijs van massa-executie in Indonesië. Archiefmap 1304. [New proof of mass execution in Indonesia. Archive folder 1304], De Groene Amsterdammer, no 41.

- Ibid.

- Jouri Boom, “Nieuw bewijs van massa-executie in Indonesië. Archiefmap 1304,” [New proof of mass execution in Indonesia. Archive folder 1304] De Groene Amsterdammer, no. 41, October 10, 2008.

- Cees Fasseur, “Rawagede is Nederlandse ereschuld, en er zijn er meer,” [Rawagede is Dutch honorary debt, and there are more] Trouw, November 26, 2008.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Ook op Sumatra richtten de Nederlanders een bloedbad aan,” [The Dutch also committed a massacre on Sumatra] NRC Handelsblad, February 13, 2016.

- See documents in the Nationaal Archief, Procureur-Generaal, nr. 1327.

- Meijer, Oostindisch doof, 106.

- In 2012 journalist Harm Ede Botje and myself spoke to several Dutch historians about the need for more research, amongst others with Ad van Liempt, Louis Zweers, Joop de Jong and Cees Fasseur.

- Hella Rottenberg, “Onderzoeker acht debat in parlement over dekolonisatie-periode ongewenst ‘Verleden behoort historici, niet politici,” [Investigator considers debate in parliament on decolonization period undesirable ‘Past belongs to historians, not politicians’] De Volkskrant, January 13, 1995.

- Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema, Op jacht naar het leven: de autobiografie van de Soldaat van Oranje [In pursuit of life: the autobiography of the Soldier of Orange] (Utrecht: Spectrum, 2000), 266.

- Abram De Swaan, “Postkoloniale absences,” [Postcolonial absences] De Groene Amsterdammer, no. 19, May 10, 2017.

- Remco Raben discusses [in Dutch] in the video Koloniaal verleden: zwarte bladzijde of blinde vlek [Colonial past: black page or blind spot], Studium Generale Utrecht University, the lack of social awareness and the way in which it’s easier to deny any dark pages by justifying the colonial past in terms of its so-called benefits.

- See for example: Harm Ede Botje and Anne-Lot Hoek, “Onze vuile oorlog,” [Our dirty war] Vrij Nederland, July 10, 2012.

- Joost Cote, “Strangers in the house: Dutch historiography and Anglophone trespassers,” Review of Indonesian and Malaysian affairs, vol. 43, no. 1 (2009): 75-94.

- Harry A. Poeze, Verguisd en vergeten; Tan Malaka, de linkse beweging en de Indonesische Revolutie, 1945-1949 [Reviled and forgotten; Tan Malaka, the leftist movement and the Indonesian Revolution, 1945-1949] (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2007). Four volumes published in revised version in Indonesian. Tan Malaka, Gerakan Kiri, dan Revolusi Indonesia: Jilid 1-4.

- Translation of the proklamasi in English: WE THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA HEREBY DECLARE THE INDEPENDENCE OF INDONESIA. MATTERS WHICH CONCERN THE TRANSFER OF POWER AND OTHER THINGS WILL BE EXECUTED BY CAREFUL MEANS AND IN THE SHORTEST POSSIBLE TIME. DJAKARTA, 17 AUGUST 1945 IN THE NAME OF THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA. SOEKARNO/HATTA, Source: Wikipedia.

- J.A.A. van Doorn and W.J. Hendrix, Ontsporing van geweld: over het Nederland/Indisch/Indonesisch conflict [Derailments of violence: about the Netherlands/Indo/Indonesian conflict] (Rotterdam: Universitaire pers, 1970), inner cover, and H. Schijf, “Van Doorns Indische lessen,” [Van Doorns Indian lessons] Mens en Maatschappij, 83.3 (2008): 210-213.

- Lou de Jong, Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog 1939-1945 deel 11A [Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Second World War 1939-1945 part 11A] (Amsterdam: Rijksinstituut voor oorlogsdocumentatie, 1984).

- Stef Scagliola, Last van de Oorlog, 92.

- Lolle Nauta, Onbehagen in de filosofie [Uneasiness in philosophy] (Amsterdam: Van Gennip, 2001), 157.

- Ad van Liempt, Een mooi woord voor oorlog. Ruzie, roddel en achterdocht op weg naar de Indonesië-oorlog [A nice word for war. Quarrel, gossip and suspicion on the way to the Indonesia War] (Den Haag: SDU, 1994).

- RTL4, Excessen van Rawagede, August 17, 1995.

- Thom Verheul, “Tabe Toean,” NCRV, 1996.

- Willem IJzereef, De Zuid-Celebes affaire. Kapitein Westerling en de standrechtelijke executies [The South Celebes affair. Captain Westerling and the constitutional executions] (Dieren: De Bataafsche Leeuw, 1984).

- Petra Groen, Marsroutes En Dwaalsporen. Het Nederlands Militair-Strategisch Beleid in Indonesië 1945-1950 [March routes and Wander tracks. The Dutch Military-Strategic Policy in Indonesia 1945-1950] (Den Haag, 1991)

- Maarten Kuitenbrouwer, Nederland en de opkomst van het moderne imperialisme. Koloniën en buitenlandse politiek 1870–1902 [The Netherlands and the rise of modern imperialism. Colonies and foreign policy 1870–1902] (Dieren: De Bataafsche Leeuw, 1985).

- Elsbeth Locher-Scholten, Ethiek in fragmenten: vijf studies over koloniaal denken en doen van Nederlanders in de Indonesische archipel 1877-1942 [Ethics in fragments: five studies on colonial thinking and doing by Dutch people in the Indonesian archipelago 1877-1942] (Utrecht: HES Publishers, 1981).

- H.G.C. Schulte Nordholt, Een staat van geweld [A state of violence] (Rotterdam: Erasmus Universiteit, 2000).

- M. Bloembergen, De geschiedenis van de politie in Nederlands-Indië; Uit zorg en angst [Out of Concern and Fear: The history of the police in the Dutch East-Indies] (Leiden: KITLV Uitgeverij, 2009).

- Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, Volledige toespraak van minister Ben Bot. [Full speech from Minister Ben Bot], August 15, 2015. From the website of NOVA.

- Alfred Birney, De Tolk van Java. (Amsterdam: De Geus, 2015).

- See also: Bart Luttikhuis and Dirk Moses (eds.), Colonial counterinsurgency and mass violence: The Dutch Empire in Indonesia (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014); Hylke Speerstra, Op klompen door de dessa: oud-Indiegangers vertellen [On clogs through the dessa: former Dutch East Indies travellers are telling] (Amsterdam: Olympus, 2015); Gert Oostindie, Soldaat in Indonesië [Soldier in Indonesia] (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2015); Maarten Hidskes, Thuis gelooft niemand mij [Nobody believes me at home] (Amsterdam: Atlas Contact, 2016); Anton Stolwijk, Atjeh: het verhaal van de bloedigste strijd uit de Nederlandse koloniale geschiedenis [Aceh: the story of the bloodiest battle in Dutch colonial history] (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2016); Manon van den Brekel, Massa–executies op Sulawesi [Mass executions on Sulawesi] (Zutphen: Walburg Pers B.V., 2017); Ronald Nijboer, Tabe Java, Tabe Indië, de koloniale oorlog van mijn opa [Bye Java, bye Dutch East Indies, my grandfather’s colonial war] (Amsterdam: HarperCollins, 2017); Piet Hagen, Koloniale oorlogen in Indonesië: vijf eeuwen verzet tegen vreemde overheersing [Colonial wars in Indonesia: five centuries of resistance against strange domination] (Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 2018); Reggy Baay, Het kind met de Japanse ogen [The child with the Japanese eyes] (Amsterdam: Atlas Contact, 2018).

- Personal conversation Remy Limpach on July 28, 2015, The Hague.

- Telephone conversation with Jeffry Pondaag, January 11, 2019, and numerous personal conversations.

- Martijn Eikhoff, Verslag van het debat Van standbeeld tot schandpaal 23 April 2018 [Report of the debate From statue to pillory April 23, 2018] Website Independence, decolonization, violence and war in Indonesia, 1945-1950.

- Histori Bersama. Discussion Colonial Statues & Van Heutsz, De Balie, Amsterdam, April 5, 2018. With Vilan van de Loo and Jeffry Pondaag. Original version in Dutch from debate centre De Balie.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Op de ‘vlucht’ neergeschoten,” [Shot on the flight] NRC Handelsblad, August 15, 2015.

- Fasseur, Dubbelspoor, 146-147.

- Martijn Eickhoff, “Weggestreept verleden? Nederlandse historici en het Rawagededebat,” [Stripped past? Dutch historians and the Rawagede debate] Groniek, nr. 194 (2013): 53.

- NCRV, “Indonesië. Reportage de waarheid boven tafel,” [Indonesia. Report the truth above the table] Altijd Wat, November 13, 2013. Video on Youtube.

- Interview Cees Fasseur by Gert Oostindie and Tom van den Berge in 2014, KITLV.

- Cees Fasseur, De weg naar het paradijs en andere Indische geschiedenissen [The way to paradise and other Indo histories] (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 1995), 272-273.

- See for example the interviews with Bank, Wesseling and Fasseur in: Meijer, Oostindisch Doof, 81 – 101; Jos de Beus, “God dekoloniseert niet: een kritiek op de Nederlandse geschiedschrijving over de neergang van Nederlands-Indië,”[God does not decolonize: a criticism of Dutch historiography about the decline of the Dutch East Indies] in BMGN, 116.3 (2001): 307-324; and H. W. van den Doel, “De stijl van de historicus,” [The style of the historian] BMGN, 116.3 (2001): 338-346.

- Meijer, 128-129.

- Ibid, 103.

- Meijer, Oostindisch Doof, 105.

- Ewald Vanvugt, Wat iedere Nederlander moet weten [Thieving state. What every Dutch person should know] (Amsterdam: Nijgh & Van Ditmar, 2016). For book review [in Dutch] see: Bente de Leede, “Recensie: Ewald Vanvugt – Roofstaat. Wat iedere Nederlander moet weten,” Recensies, Jonge Historici, last modified April 18, 2016.

- Kloet, “Typhoon kruipt in de huid van een slaaf: ‘Laten we nu het gesprek aangaan’,” [Typhoon takes on the role of a slave: ‘Now let’s start the conversation’], artikelen, overzicht, 2016, maart, VPRO 3voor12.

- Carolien Stolte and Alicia Schrikker (eds), World History – a Genealogy: Private conversations with World Historians, 1996-2016 (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2017), 19.

- Frances Gouda en Lizzy van Leeuwen, “Gordelroos van Smaragd,” [Shingles from Emerald] De Groene Amsterdammer, October 19, 2016.

- OVT Radio interview Rudy Kousbroek by Remco Raben, “Geschiedenisgasten,” [History guests]OVT, July 14, 2002.

- Interview Fasseur, Kitlv.

- Stef Scagliola, conversation in person, September 5, 2016.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Iedereen wist het, maar niemand kon het zeggen,”[Everyone knew, but nobody could tell] NRC Handelsblad, September 16, 2016.

- Niels Mathijssen, “Laat historici ontvankelijker worden voor afwijkende perspectieven,”[Let historians become more receptive to deviating perspectives] Over de muur, October 4, 2018.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Iedereen wist het, maar niemand kon het zeggen“.

The way forward

- Museum Bronbeek, Oorlog! Van Indië tot Indonesië 1945 – 1950 [From The Indies to Indonesia 1945 – 1950], exhibition newspaper, February 19, 2015.

- Jos Janssen and Martin van den Oever, “Libera Me, men moet kennen de geschiedenis,” [Libera Me, one must know the history] Youtube Omroep Gelderland, October 18, 2015.

- Published as Suzanne Liem, De Weduwen van Rawagede – Getuigen van de dekolonisatieoorlog [The Widows of Rawagede – Witnesses to the decolonization war] (Amsterdam University Press, 2015).

- Nicole Immler, “Narrating (in)justice in the form of a reparation claim: bottom-up reflections on a postcolonial setting – the Rawagedecase,” in Understanding the age of transnational justice: crimes, courts, commissions and chronicling, ed. Nancy Adler (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2018), 149 – 170; and Human rights as a secular social imaginary in the field of transnational justice, the Dutch-Indonesian Rawagede case in: Social imaginaries in a globalizing world, ed. Hans Alma and Guido Vanheeswijck (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 193 – 220.

- Remco Raben, Wie spreekt voor het koloniale verleden? Een pleidooi voor transkolonialisme [Who speaks for the colonial past? A plea for transcolonialism], inaugural lecture, University of Amsterdam, September 28, 2016.

- See for example the discussion on author Kester Freriks pamphlet on colonialism: Kester Freriks, “Tempo Doeloe, ook een mooie tijd,” [Tempo Doeloe, also a good time] NRC Handelsblad, October 5, 2018; Thomas Smits, Klaas Stutje and Suze Zijlstra, “Koloniaal geluk is niet los te zien van koloniaal leed,” [Colonial happiness cannot be viewed separately from colonial suffering] NRC Handelsblad, October 9, 2018; Reza Kartosen-Wong, “Tempo Doeloe? Een gruwelijke bezetting,” [Tempo Doeloe? A horrible occupation] NRC Handelsblad, October 13, 2018; Remco Raben, “Nooit meer Indië, de zes denkfouten van Kester Freriks,” [Never again Indie, the six errors of thinking by Kester Freriks] de Nederlandse Boekengids, December 16, 2018.

- Siep Wynia, “De Joke Smitprijs voor Wekker is een grote fout,” [The Joke Smit prize for Wekker is a big mistake] Elsevier, December 12, 2017.

- Anne-Lot Hoek, “Een onderzoek naar schuld en boete,” [An investigation into debt and fine] NRC Handelsblad, November 22, 2016.

- Anne-Lot Hoek & Martijn Eickhoff, “Luister ook eens naar de Indonesische stemmen,” [Also listen to the Indonesian voices] NRC Handelsblad, January 15, 2019, based on several email and live conversations with Ariel Heryanto.

- Bonnie Triyana, “Dekolonisatie of rekolonisatie?,” [Decolonization or recolonization] from 12.37 min, filmed September 13, 2018, Pakhuis de Zwijger, Amsterdam.

- Iswanto Hartono, “Wie wil vergeten moet eerst herinneren,” [Whoever wants to forget must first remember] NRC Handelsblad, September 29, 2017. For more information [in English] about the exhibition Europalia Indonesia, see the website De Oude Kerk.

- See website of the research project Independence, decolonisation, violence and war in Indonesia 45-50.

- Open letter to the Dutch government. Bezwaren tegen het Nederlandse onderzoek “Dekolonisatie, geweld en oorlog in Indonesië, 1945-1950” [Objections to the Dutch study “Decolonization, violence and war in Indonesia, 1945-1950]. And the reply of the Dutch government [English translation] from the website of Histori Bersama.

- Histori Bersama, Video message Francisca Pattipilohy, Not invited to speak during the second public meeting of the Dutch research on 1945-1949 September 13, 2018, Amsterdam.

- Shortly after this publication, an article in De Groene Amsterdammer was published ‘Heeft een gedicht niet ook gewicht?'[Does a poem not also have a weight?] by Niels Mathijssen on 17 April 2019 in which the final investigation of the research project is criticized by various historians, including Anne-Lot Hoek. They argue that Indonesian sources are not considered enough.

- Sanne Rotmeijer (KITLV), Marieke Bloembergen (KITLV) en Priya Swamy (Museum of World Cultures), “Academic research in a decolonizing world:towards new ways of thinking and acting critically?,” workshop held October 8-9, 2018, KITLV, Leiden. This two-day interdisciplinary workshop set the stage for deepening critical awareness of past and present academic positions and practices in relation to the call to decolonize academia that has recently intensified inside and outside of academic institutes worldwide. A critical conversation about this matter was not only topical, but also much desired among scholars in Dutch academia, and particularly in Leiden with its long tradition of orientalist research and collecting. This workshop therefore provided a much needed space for reflecting on and questioning colonial predicaments in academic research and teaching.

- Lise Koning, “Wie schrijft de geschiedenis?Verslag KNHG Jaarcongres: uitsluiting, stilte en taboe in de geschiedenis,” [Who writes the history? Report KNHG Annual Congress: exclusion, silence and taboo in history] KNHG website, December 13, 2018.

- Anne-Lot Hoek reflected on the sensitivity of the term decolonization during the launch meeting of Bridging Humanities, June 2018, see the video here.

Willem Bosch ‘champion of the Javanese’

Willem Bosch (1798-1874) was a medical doctor who worked in the Dutch East Indies during the 19th century where he saw the harsh effects of the colonial 'cultivation system' policy, which made the population to face famine and disease. This led Bosch to voice organised protest against the Dutch government. Inspired by the British legendary Anti-Corn Law League, he established a pressure group in the Netherlands that was to speak up for the rights of the Javanese. His movement came to represent the ‘ethical movement’ in colonial politics, in line with other more famous protesters of the time, such as the writer Multatuli or the liberal politician Van Hoevell. This movement acknowledged that the Dutch had a debt of honour towards the Indonesians, and therefore had to raise the living standards of the native population, yet it was still defined from a moral superior position, as it did not fundamentally criticise the premise of colonialism. In this section Maartje Janse provides an introduction to the life of Willem Bosch. She had published about Bosch before, as part of her ongoing academic research into the involvement of citizens in nineteenth-century politics, specifically within single-issue organizations.

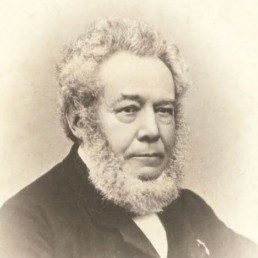

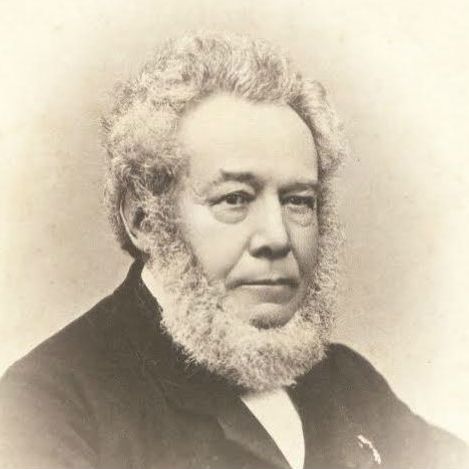

Photo: Willem Bosch, courtesy Family Bosch

When Willem Bosch died in 1874, one of the newspapers wrote: ‘he will be remembered as the Javanenkampioen (‘champion of the Javanese’); posterity will mention him in the same breath as Multatuli (the well-known writer of the Dutch novel Max Havelaar)[efn_note]For more on the relation between Willem Bosch and Multatuli, see Maartje Janse, “‘Om eene hervorming tot stand te brengen, behoort men te weten, wat men wil’. Multatuli en de Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan (1866-1877),” [To bring about a reform, one must know what one wants. Multatuli and the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese] in Multatuli Jaarboek (Hilversum: Verloren, 2016), 35-50.[/efn_note] and Van Hoëvell (a liberal politician known for fighting for the abolition of slavery and the cultivation system in the Dutch East Indies). Bosch, Van Hoëvell, and Multatuli had all attempted to popularize the notion that ‘the Javanese’, like Dutch citizens, ‘deserved righteous treatment, education and civilization’. However, according to his admirers, Willem Bosch was even more important than his fellow-reformers. All three had aroused awareness of injustice among Dutch citizens, but Bosch had found a way to channel this feeling into political mobilization. He had created a ‘point of association’ or a pressure group, as we would call it today.

But where Multatuli is still remembered as one of the most important authors in Dutch literature, and one of the most outspoken critics of colonial abuses, Willem Bosch was all but forgotten by the time I came across his story in 1997, when I was still a student. In the years that followed I have published about Willem Bosch and his organization De Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan (Society for the Benefit of the Javanese) in several places. This text can be read as an introduction to Bosch, based on (and linked to) those more comprehensive publications.[efn_note]Most importantly: Maartje Janse, De afschaffers, publieke opinie, organisatie en politiek in Nederland 1840-1880 [The abolitionists, public opinion, organization and politics in the Netherlands 1840-1880] (Amsterdam: Wereldbibliotheek, 2007); Maartje Janse, “De balanceerkunst van het afschaffen. Maatschappijhervorming beschouwd vanuit de ambities en de respectabiliteit van de negentiende-eeuwse afschaffer,” [The balancing art of abolition. Societal reform viewed from the ambitions and respectability of the nineteenth-century abolitionist] De Negentiende Eeuw 29, 1 (2005): 28-44. These publications show that prior to the founding of the first political parties in the Netherlands, some citizens organized themselves into associations to promote the abolition of all kinds of social abuses. These single issue movements were concerned with the abolition of slavery, alcohol abuse, taxes on newspapers, the Education Act of 1857, and in the case of Willem Bosch and his Society for the Benefit of the Javanese, with the cultural system in the Dutch East Indies. The first "abolitionists" claimed to be apolitical and to be protesting against what was wrong in society based on their beliefs, feelings and conscience. But gradually their protests became politicized, ultimately changing the nature of politics. It was partly due to the abolitionists that towards the end of the nineteenth century politics increasingly involved questions of morality and religion, and that more and more people thus more strongly identified with politics, and became more involved in politics.[/efn_note]

Maartje Janse spoke about Willem Bosch twice during the process. The first time involved an interview captured on film, which was screened at the Voice4Thought festival in 2016 and based on which the pamphlet was made (see also the section Co-creation). Video by Sjoerd Sijsma, Eyeses, 2016. The second was an interview on OVT radio in 2018, in which Maartje Janse and Anne-Lot Hoek were invited to speak about the publication in 2018 (the full interview is part of the section Introduction).

The cultivation system

The cultivation system (cultuurstelsel in Dutch) was a system of taxation that Governor-General Johannes van den Bosch implemented in 1830 in order to turn the Dutch East Indies into a more profitable colony. The cultivation system demanded one-fifth of the arable land in the colony for the cultivation of cash crops such as coffee, indigo, and sugar. These crops were then sold on the world market, and the revenues went directly to the Dutch treasury. People who did not own land had to work on government fields for one-fifth of their time. Javanese farmers received only a small payment in return and had less time and arable land left to devote to their own needs. The government, however, did not tolerate any form of criticism of this lucrative system. When Willem Bosch, in his capacity of government official, suggested that the Javanese had become more susceptible to disease because of famine, the Dutch government strongly condemned him for suggesting the Javanese were being exploited. In one of the governmental reports, he was even labelled as an ‘enemy of the state’.

For a long time, the Dutch colonial policy was aimed at extracting maximum profit by exploiting the colonies in the most efficient way possible. The humanitarian consequences of these policies were only of minor interest for both the Dutch government and people. It took until the 1840s before Dutch citizens slowly but surely began to voice protest against slavery in the Dutch West Indies (present-day Suriname and Curaçao). Public opinion was changing, and individuals started to raise their voices against the use of slave labour on plantations.[efn_note]See for example: Maartje Janse, “Nederlands protest tegen de slavernij,” [Dutch protest against slavery] Slavernij en Jij. or Maartje Janse, “Meer protest tegen slavernij dan gedacht,” [More protest against slavery than has been thought] Kennislink, October 17, 2011; or Maartje Janse “Holland as a Little England’? British Anti-Slavery Missionaries and Continental Abolitionist Movements in the Mid Nineteenth Century,” Past & Present, Volume 229, Issue 1 (November 2015): 123–160, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtv037 [restricted access].[/efn_note]

Slavery also existed in the Dutch East Indies, but it was less visible than slavery in the West Indies. Slavery is easily linked to the cultivation system because, like slavery, the cultivation system in the East Indies was a system of forced labour. However, unlike their enslaved counterparts in the West Indies, Javanese labourers did receive some—even if small—payment and had more freedom than slaves. Partly because of criticism of the cultivation system, new colonial policies were introduced in the 1870s, leading eventually to the system’s abolition. The passing of the Agrarian Law and the Sugar Law gave more freedom to the private sector, and the government gradually withdrew from cultivation and left the exploitation of land to private investors. In the long run, however, the harsh exploitation of the private investors proved to be even worse for many Javanese than the cultivation system.

For a visual impression of the life in the Dutch Indies during the 19th century, see the pamphlet made by Sjoerd Sijsma.

A medical doctor in the Dutch East Indies

Willem Bosch’s biography reads like a Victorian novel. He was born in 1798 in Amsterdam as the son of a wealthy carpenter. According to his later memoirs[efn_note]copies of original Willem Bosch memoirs p. 1-21; Willem Bosch memoirs p. 22-42.[/efn_note], Bosch endured a strictly religious and ‘heartless’ upbringing. His family got into financial trouble, and Willem had to earn his own living from age 13 when he became orphaned. Wanting to achieve more in life, he studied medicine at night and qualified to become a ship’s doctor. With little experience, he then set off for the Dutch East Indies.

Death, disease, and retaining good health were central themes of life in the nineteenth century. For a large part, the ‘colonial experience’ was determined and limited by the dangers of tropical diseases. Bosch, who quickly moved up the ladder within the Military Medical Service and made it to chief in 1845, discovered that this was indeed the case. The fact that he had made it to the highest rank in his position without an academic education or contacts in the colony can be attributed to his remarkable diligence and ambition. Unlike his colleagues, who spent their spare time ‘in a dissolute manner’, Bosch lived according to a rigid regime. His sense of responsibility partly derived from an instinct for self-preservation. He believed that self-control, discipline, and order were the only ways to reduce one’s susceptibility to tropical diseases.

Portraits of Willem Bosch. The first shows Willem Bosch in his younger years, portrayed in uniform, although he rarely wore that to the annoyance of his superiors.[efn_note]A.H. Borgers, Doctor Willem Bosch en zijn invloed op de geneeskunde in Nederlandsch Oost-Indië [Doctor Willem Bosch and his influence on medicine in the Dutch East Indies] (Utrecht, 1941).[/efn_note]. The second is a photograph of Bosch at a later age. Private Collection, Courtesy Family Bosch.

Criticism of the government

Bosch was a medical doctor who showed considerable empathy for his patients and did everything in his power to ease their suffering. His motto was: ‘Travailler sans cesse au soulagement de l’humanité souffrante’ (‘work ceaselessly to ease humanity’s pain’). He took it personally when he was unable to help his patients. When Bosch was chief of the Military Medical Service, he also felt responsible for the well-being of the native population.

In 1846 an epidemic scourged Central Java. When the epidemic worsened, Bosch tried to find ways ‘to save the ones in need, and to protect the Netherlands from stain and the painful reproach that she is not even willing to renounce 1/4000 of the 30 million guilders that were obtained by Javanese labour, to provide food and plentiful quinine, that in truth, the Javanese begged for’. In a report to the government, Bosch advised setting up field hospitals and providing blankets, quinine, and rice, since the lack of food, according to Bosch, was one of the main factors that exacerbated the epidemic.[efn_note]For more on Bosch’ career in the Military Medical Service see Borgers, Doctor Willem Bosch.[/efn_note]

The report was not taken lightly. The Dutch authorities considered it a direct assault on the government: distributing rice under the government’s budget would mean admitting the Javanese were suffering from hunger and disease on account of the cultivation system. Bosch, on the other hand, would devote the rest of his life to fighting the unjust treatment of the Javanese. He did so in multiple ways.

Protest!

From the 1840s onwards, criticism of official Dutch colonial policy began to take new forms. Until 1848 the king was not accountable to Parliament for colonial policy. The king held a so-called royal prerogative, which meant he had carte blanche to do what he wished. Liberals, however, deemed it important that the government be held accountable for the colonial policy pursued. To start with, information about colonial policy should be more freely accessible to critically minded politicians and civilians alike. They advocated ‘transparency in colonial affairs’.

To keep the spectre of revolution at bay, a new, liberal constitution was implemented in 1848 in the Netherlands, and the liberals—under the leadership of Thorbecke—were now in government. Under this new constitution, the government was made accountable to Parliament. The Minister of Colonies was required to report on his colonial policy and defend it in Parliament, during which he also had to inform members of Parliament about the colonial budget. This new constitution resulted in a new, lively debate about colonial affairs, including the cultivation system. Another important result of this new constitution was the new notion of citizenship, which led Dutch citizens to become more involved in colonial affairs.

Citizens began to voice opposition to social problems because the new political system gave them a sense of moral responsibility. As a member of the board of Bosch’s pressure group Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan put it: ‘The time of authority is over, both in a religious and political context. The people are no longer following blindly: they want to see, see for themselves and judge what is happening. And in that, they are right! We do not have to blindly follow and comply because the government says so. We do not have to swallow the government’s policies, hook, line, and sinker. The people do not exist for the government; the government exists for the people.’ This last idea had far-reaching consequences: when public opinion demanded change, the government should listen to the public’s voice, ‘or otherwise abdicate’.[efn_note]For more on the changing political culture see: Maartje Janse, “Representing Distant Victims: The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880,” BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review, 128-1 (2013): 53-80, http://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.8355 [open access].[/efn_note]

Later life: in search of recognition

Because of his weak health, Bosch stopped working as a doctor after he retired from his post in 1856, which made him one of the many retired publicists of his time. Upon his death in 1874, his ‘In Memoriam'[efn_note]Arnhemsche Courant, May 21, 1874. Link[/efn_note] read: ‘Even after a turbulent life, he had managed to keep a willingness that one finds only in a young person to make progress in every aspect of life. He had a fierce spirit of mind, which made it impossible for him to stop working, even during his last days. He has been one of the most fervent opponents of the cultivation system. [...] a man of character in the best sense of the word, open and honest, up-front and loyal, who stood for what he believed in and made sacrifices for his beliefs.’

Willem Bosch’s personality can be read only partly from this outline, but it is clear that he had a difficult life, especially as a child and young man. From his unfinished autobiography it can be seen that he complained about this, but we also get a sense that he was proud of his status as a self-made man, for he described his childhood in great detail in Dickensian style. Loneliness and lovelessness made him a lone warrior against indifference and injustice. It is also striking that he did everything in his power to climb the career ladder: he was an ambitious man. In this sense, a position as a member of Parliament would have crowned his career. Bosch chose a different path, however, by voicing opposition outside of government. For Bosch, politics meant pettiness. Instead he wanted to create a massive public movement. Going down in history as a fighter for the Javanese remained his ambition to the end.

His strong personality, powerful statements, and energetic attitude, made Bosch the ideal candidate to play a prominent role in the colonial debate. He had one weakness, however: he did not handle criticism well and he could not put things into perspective. He felt his motives were always pure and noble, and as such he felt deeply hurt by criticism. He could be quite blunt about this. He dismissed criticism against his use of statistics, for example, as a conscious twisting of the truth. He felt he held all the right answers, and for others not to recognize this discouraged him. Time and time again he felt unappreciated and unjustly treated, even by friends and like-minded campaigners when they were not as impassioned as he himself was. Even though he had remained engaged with the struggle for the Javanese until the end, he had died a disappointed man. ‘The offensive disappointments that Bosch had to cope with, the slander that he had to bear, even during the last days of his life, but most of all the sad indifference that like-minded people showed—had shocked his previously strong body. The once valiant warrior had become pessimistic and despondent in the last days of his life.’[efn_note]‘In Memoriam’, Nederland en Java, June 1, 1874.[/efn_note]

Willem Bosch died on 19 May 1874 at his residence in Arnhem, feeling underappreciated as a warrior for truth and justice. He had hoped and expected that future generations would recognize him as a champion for the rights of the Javanese. He also expected gratitude from the Javanese after his death and the recognition that he had indeed been their ‘champion’, their advocate.

We protest! But how?

Willem Bosch tried to change colonial policy in different ways. By analysing these protest forms, a picture emerges of nineteenth-century practices of protest and the way they evolved. Bosch first challenged colonial policy as chief of the Military Medical Service. In 1849 he wrote a critical report in which he advised the Dutch government to distribute rice, since the Javanese population was suffering from famine, he argued, which caused disease. The report was not well received, however, as the Dutch government was unwilling to admit the Javanese population was suffering under their rule.

Bosch was indignant about the situation and wanted to inform Parliament. One of his friends, Wolter Baron Van Hoëvell, whom he met during his time in Batavia, was a member of Parliament, and Bosch did not hesitate to send him confidential government documents in order for them to be made public. This had some effect, but it did not lead to the massive public indignation that Bosch had hoped for. When Bosch retired early in 1854 and settled in the Netherlands permanently, many people expected he would become a member of Parliament like Van Hoëvell, in order to carry on his fight. Instead, Bosch never stood as a candidate for election but pursued other ways to get his voice heard as a citizen.

In the years that followed, he published multiple pamphlets in which he tried to demonstrate by means of statistics that the Netherlands would be better off caring for the Javanese. He argued that a healthy and happy Javanese population would benefit everybody, since it was the Javanese who made the colony profitable.[efn_note]For some of Bosch’s publications see: Willem Bosch, ‘Ik wil barmhartigheid en niet offerande.’ Eene wekstem aan Nederland tot barmhartigheid, rechtvaardigheid en pligtsbetrachting jegens de Javanen [‘I want mercy and not sacrifice.’A wake-up call to the Netherlands for mercy, justice and duty to the Javanese] (Arnhem: Breijer, 1866). For a full list of Bosch’s publications see Bosch’s Bibliography.[/efn_note]

In 1865 Bosch came up with the idea of setting up a pressure group. He was inspired by the stories of the legendary Anti-Corn Law League. This British association, which battled high import duties on corn in 1839–1846, was one of the first pressure groups in history. In the years 1823–1833, the British Anti-Slavery Society had already shown that pressure groups could function as an efficient method in a political conflict. The Anti-Corn Law League was famous primarily because it had protested in a professional and efficient way—even more so than the Anti-Slavery Society—and thus had influenced public opinion and Parliamentary elections. It was one of the reasons why the Corn Laws were abolished in 1846. Organizing a political pressure group had long been controversial in Britain as well.[efn_note]For more information on the debates about pressure groups see: Maartje Janse, “A Dangerous Type of Politics? Politics and Religion in Early Mass Organizations: The Anglo-American World, c. 1830,” in Joost Augusteijn, Patrick Dassen, and Maartje Janse (eds), Political Religion Beyond Totalitarianism: The Sacralization of Politics in the Age of Democracy (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 55–76; and Maartje Janse, “‘Association Is a Mighty Engine’. Mass Organization and the Machine Metaphor, 1825 1840,” in Maartje Janse and Henk te Velde (eds), Organizing Democracy: Reflections on the Rise of Political Organizations in the 19th Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 19-42.[/efn_note]

In 1865 Richard Cobden, leader of the Anti-Corn Law League, passed away, and the papers and journals were filled with his life story and references to the League. In 1866, Bosch confessed his gratitude openly to the leaders of the Anti-Slavery Society and the Anti-Corn Law League: ‘We should follow the footsteps of Wilberforce and Cobden, albeit with less talent and energy. They have taught us what one can achieve by harnessing the power of the people with persistence and determination.’[efn_note]On the importance of the Anti-corn law league see Maartje Janse's article in European Review of History here.[/efn_note]

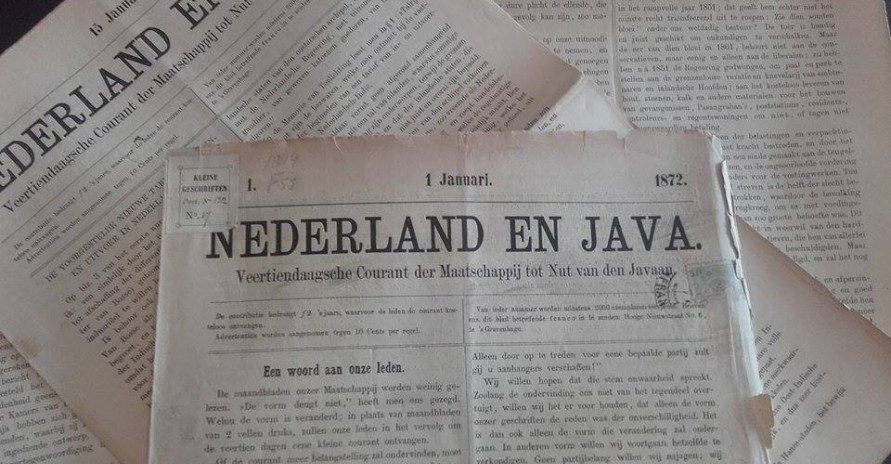

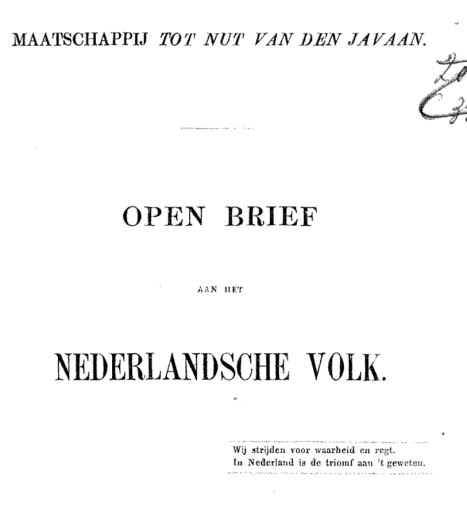

Archival protest material of the Society for the Benefit of the Javanese.

Civil society or state task?

In the decades after 1848 most politicians still thought the state should play only a minor role in society. Maintaining public order and guarding the frontiers and the treasury were the most important duties of the state. When citizens asked the government to intervene in social problems, such as the effects of poverty, alcohol abuse, child labour, slavery, and the cultivation system, the general consensus was that it was not the role of the state ‘to encourage social prosperity’—that is, to make its citizens happy. Citizens were in charge of their own happiness, and social improvement was the responsibility of civil society. Hence, many reform associations prospered in the Netherlands.

One of the best-known associations in this respect was the Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen (‘Society for Public Welfare’). It was founded in 1784 to stimulate the Dutch economy by, for example, organizing a better education system for Dutch citizens of low socio-economic background. Bosch decided to form a similar association: De Maatschappij tot Nut van de Javaan (‘Society for the Benefit of the Javanese’). The obvious similarity between the name of Bosch’s association and the Society for Public Welfare evoked trust—it reminded people of the well-known and respectable association—while at the same time expressing strong criticism against the way the Netherlands treated her colonies. The Dutch had exploited the Javanese for such a long time; it was time to take some action that would benefit the Javanese.

With this accusation and proposal, Bosch and his Maatschappij tot Nut van den Javaan came to represent the ‘ethical movement’ in colonial politics. Criticism, increasingly explicit, that the Netherlands had an eereschuld (‘debt of honour’) to its colonies, led to the suggestion that this debt could be repaid only by investing in education and infrastructure in the Dutch East Indies, in order to ‘elevate the population to a higher level of civilization’. In 1901 the ‘ethical policy’ even became official government policy.[efn_note]See also: Association Life in the Netherlands (from 1780) and Representing Distant Victims The Emergence of an Ethical Movement in Dutch Colonial Politics, 1840-1880.[/efn_note]

‘Society for the Benefit of the Javanese’

Once Bosch had decided to form a pressure group, the next step was to look for allies who could and would help him. As a person with outspoken opinions and a controversial style, he found it difficult to collaborate with others. In particular, Bosch’s reproach that missionary work was hypocritical as long as social and political problems still existed shocked most of his contemporaries. Because of this, many orthodox Protestants did not want to work with him. He published a pamphlet[efn_note]Bosch, ‘Ik wil barmhartigheid en niet offerande’.[/efn_note] which was an emotional appeal to the Dutch people, and in 1866, 160 people from all over the country expressed their support: the Maatschappij was founded. Bosch’s fellow board members were somewhat more circumspect than he was, so initially the publications of the association did not even explicitly demand the immediate abolition of the cultivation system.

Bosch called specifically upon Dutch women to join the association in his publication Tweede Wekstem (‘Second Wake-up call’).[efn_note]Willem Bosch, Tweede wekstem aan Nederland tot barmhartigheid, rechtvaardigheid en pligtsbetrachting jegens de Javanen [Second wake-up call to the Netherlands for mercy, justice and duty to the Javanese] (Arnhem: Breijer, 1866).[/efn_note] He urged ‘Dutch mothers’ to identify themselves with Javanese women and to act out of empathy towards ‘those unhappy, not as white but no less tender-hearted mothers’, who even sold off their own children, driven into poverty and despair as they were by the cultivation system. According to Bosch, the great sensibility of women, their motherly love and empathy, made them particularly suited to protesting against the cultivation system.

That Bosch invited women to become members was unusual. ‘It is politics, something women have nothing to do with, nor something they should interfere with’: this was the general consensus. But the Maatschappij did not share this conception. ‘Is there any politics in the lamentation of those fellow human beings who are breaking under the toil caused by our low-paid labour? Do you have nothing to do with this? Should you not interfere with this, you compassionate women?’ Bosch almost expressed a feminist conception: according to him, women were ‘made for something better [...] than the usual routine society asks of you’. To his disappointment, there were only 20 women among the 2,500 members of the association.